First Person: The lure of the lost play | reviews, news & interviews

First Person: The lure of the lost play

First Person: The lure of the lost play

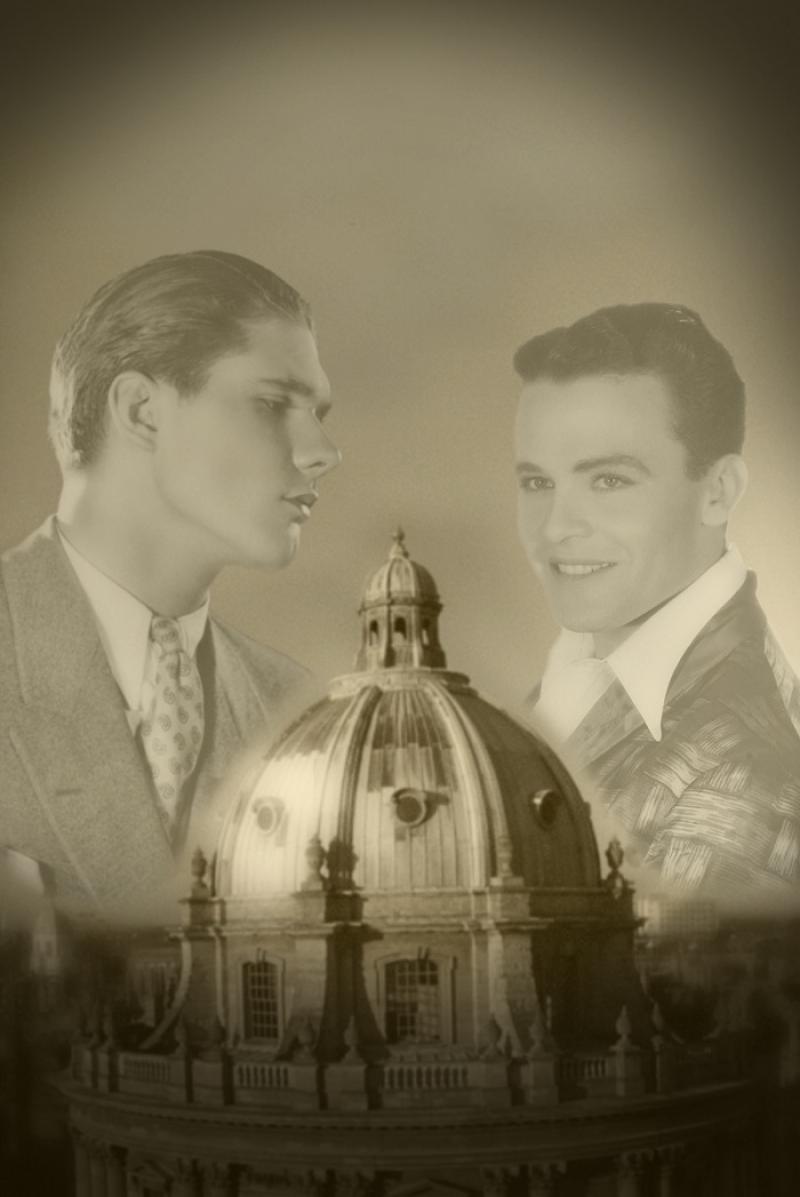

As Rattigan's debut is staged after 80 years, its director ponders the rise of the rediscovery

About a year ago, Alan Brodie, who is the agent for the estate of Terence Rattigan, sent me a handful of his more obscure plays. I had worked with Alan before on a revival of Graham Greene’s first play, The Living Room, so he knew I had a penchant for what are now termed "rediscoveries".

It’s a young writer’s play: imperfect, emotionally raw, sketching out ideas which will later become tropes of his mature work. But it also has bags of charm, writing about what it’s like to be 22 years old in the way that only a 22-year-old can. For me it had a dual appeal. It was fascinating for any admirer of Rattigan’s work, but it also functioned on its own terms as a play of the early 1930s, particularly in its frank treatment of the sex lives of the undergraduates it portrays.

Why stage such a play now? When I started working as a director on the London fringe in 2006, the term "rediscovery" was not so widely used as it is now. The brilliant and inexhaustible Neil McPherson at the Finborough in Earl's Court was – and probably still is – the noisiest champion of the rediscovery, regularly turning out gems of plays which hadn’t been seen for decades. Sam Walters at the Orange Tree in Richmond was similarly exploring the neglected corners of, particularly, the late Victorian and Edwardian repertoire. But by and large, the fringe was a place for new work.

The rewards of producing rediscoveries are nearly outweighed by the challenges

Over the last decade, rediscoveries have become a staple of the fringe, and have started to influence the programming of the mainstream as well. There is an audience for rediscovered plays. When I revived Stephen Sondheim’s first musical, Saturday Night, in 2009, it enjoyed a dream reaction. It began at Jermyn Street Theatre, recently something of a rediscoveries powerhouse, before transferring to the Arts Theatre. Partly, being set on 1929 Wall Street, it caught a zeitgeist of the post-Lehmann Brothers crash. But mostly fans of Sondheim came out to see something they’d not caught before. It’s particularly exciting to see an early work by a known composer or writer. Sondheim refers to Saturday Night as his "baby pictures", but when he came to see our revival he was delighted to see a packed house responding wholeheartedly to his 24-year-old's efforts. Just sometimes, a rediscovery proves so successful that it takes its place in the canon of regularly revived plays – think Journey’s End or An Inspector Calls.

The rewards of producing rediscoveries are nearly outweighed by the challenges. They are ferociously difficult to fund. They’re not new work, so all the money earmarked for new writing is unavailable. They’re not classics, so they’re not good for corporate funding or private patrons either. Over the years, my company, Primavera, has painstakingly built relationships with a handful of people with a passion for more off-the-beaten-track quarters of the repertoire, but it’s not easy. Rediscoveries are also hard to cast. Ring a theatrical agent and offer their client Lady Bracknell, and there’s a fair chance the agent will have heard of the play and the part. Try that with a leading role in a rediscovery and it’s a much tougher proposition. Everyone is taking a gamble on something pretty unknown. Audiences, though keen to make new discoveries, are cautious: they wait for good reviews before booking a ticket, whereas if Hay Fever is on, they can make a judgement long in advance. So it’s financially perilous every time.

Fashions change. Plays may lie neglected because they failed on a first outing, or because their writer has fallen from public or critical favour. Rattigan probably didn’t help his cause by appearing to pick a fight with the Angry Young Men of the Royal Court in the 1950s. Still worse was his satirical invective against his own audience – "Aunt Edna", as he termed the ladies who came up from Surrey to see matinees of his plays. So for over a generation of theatregoers Rattigan’s reputation was as a fusty, polite dramatist. A now-legendary revival of The Deep Blue Sea by Karel Reisz at the Almeida in 1993 began the resuscitation, but it wasn’t until the centenary of Rattigan’s birth in 2011, which saw a cluster of star-studded revivals, that he really came roaring back into the public domain. Now a new generation of actors and theatregoers are discovering a Rattigan who seems urgent and vital; however well he may chronicle the fabled "stiff upper lip", Rattigan’s plays actually speak from the heart in a way that, in the language of the 1930s, can be genuinely shocking.

In one critical respect, we can be confident that our revivals today are closer to Rattigan’s intentions than the original productions were. In the absence of a Lord Chamberlain waving a blue pen over the more scandalous sections of Rattigan’s texts, we can now perform Rattigan’s work uncut. Of course, this doesn’t just apply to Rattigan. When I worked for Peter Hall on Coward’s The Vortex at the Apollo in 2008, we discovered a few lost lines suggesting a lesbian subtext between Florence and her close friend Helen. We were able to reinstate those lines, long cut by the Lord Chamberlain, adding rich ambiguities to the plot. Dan Rebellato, who has edited the text of First Episode, has likewise reinstated virtually all the material originally censored. The result is a play which is far more explicit in its treatment of sex, and particularly of sex between men.

For me there’s no essential difference between rehearsing a rediscovery or any other play. George Devine – who was a contemporary of Rattigan’s at Oxford, and is part of the inspiration for one of the characters in First Episode – had a well-known maxim at the Royal Court about doing "new plays like classics, and classics like new plays". A rediscovery is neither a classic nor a new play, but it’s much closer to the latter. Sadly, Rattigan isn’t around to help out with our rehearsals. But the process – fine-tuning the text, mining the characters, finding the jokes – is pretty much like working on a new play. And as audiences settle into their seats to enjoy (or not) Rattigan’s debut drama over the next month, it’s a huge thrill to be introducing them to a new, old play.

- Tom Littler is artistic director of Primavera and a freelance director

- First Episode at Jermyn Street Theatre until 22 November and then the Simpkins Lee Theatre, Oxford, on 28 and 29 November

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Add comment