Classical CDs Weekly: Barry, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Shostakovich | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs Weekly: Barry, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Shostakovich

Classical CDs Weekly: Barry, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Shostakovich

A startling new comic opera, picturesque orchestral music and a terrifying Soviet symphony

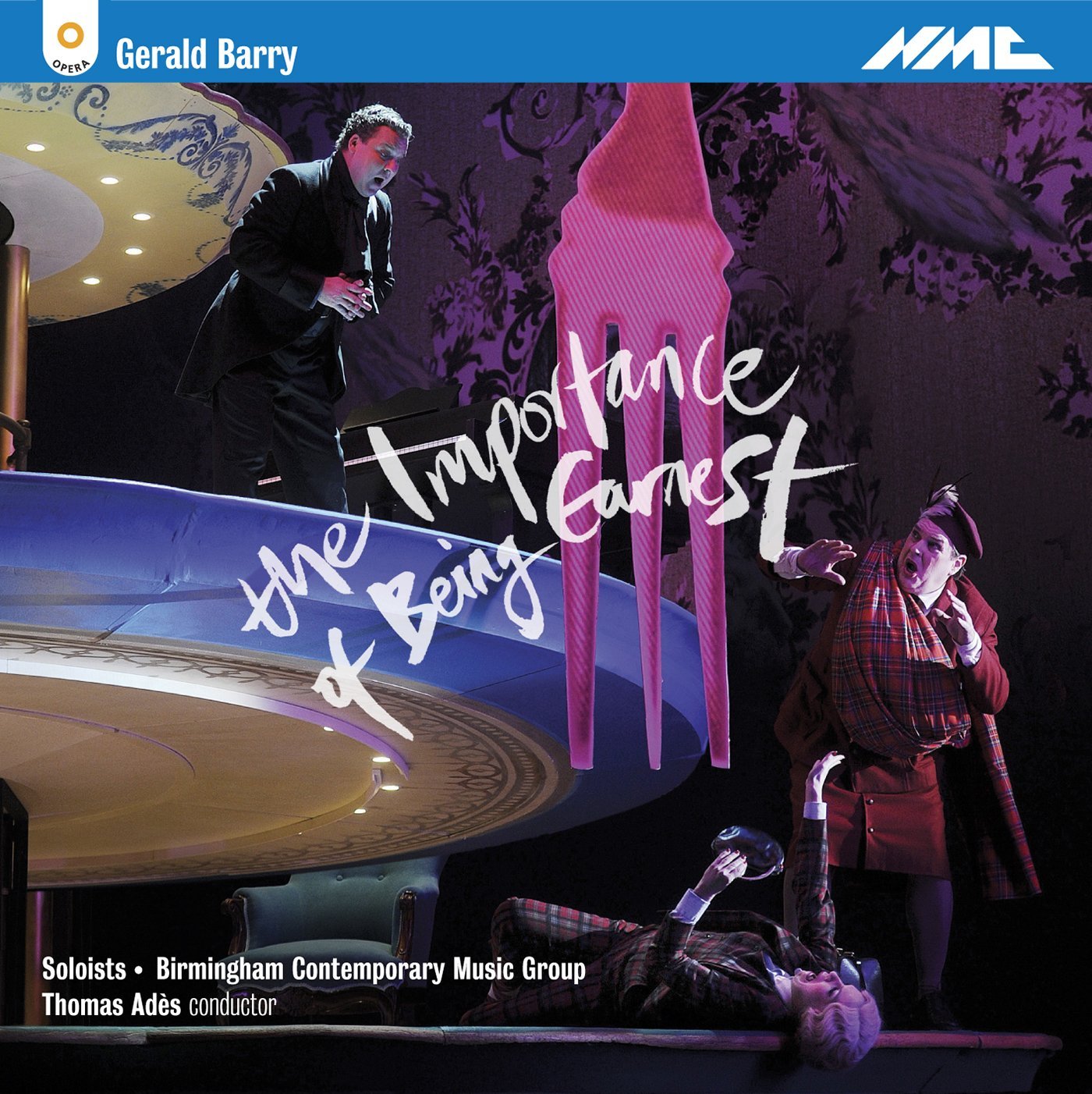

I missed the live performances of this work; being allergic to Wilde as a dramatist, I wasn't in any hurry to assimilate The Importance of Being Earnest as contemporary opera. But this is a superb live recording – edgy, brilliantly sung and boasting electrifying playing from Thomas Adès' Birmingham Contemporary Music Group. And while I didn't laugh out loud, I was beguiled and entertained by Gerald Barry's ruthless deconstruction of Wilde's original. Which could probably form the basis of a very bland, polite operetta in the wrong hands. Not here, with a stripped down libretto underscored by dazzingly inventive music. Beginning with the composer playing a mad distortion of "Auld Lang Syne" on a creaky offstage piano. Barry can't keep still stylistically; there's an extended atonal exchange about cucumbers and crumpets, and plenty of delectable, Stravinskian wind writing.

Bass Alan Ewing makes an unlikely, though wholly credible Lady Bracknell – the famous handbag line is intoned in a fearsome, guttural rasp which will have your speakers wobbling. Barbara Hannigan's Cecily is required to sing unfeasibly high, and the standout scene has her and Katalin Károlyi's Gwendolin shouting at each other through megaphones while a percussionist shatters crockery. It's bonkers, in a good way. Peter Tantsits and Joshua Bloom as Jack and Algernon shine, effortlessly negotiating Barry's crueller vocal demands. The whole thing lasts less than 80 minutes. Paul Griffiths's notes are good, and there's even - shock - a libretto. Highly recommended – though this work would benefit even more from a DVD release.

Schumann's symphonies have been rehabilitated, and Brahms has never gone out of fashion. It's a shame, then, that much of Mendelssohn's orchestral output is so seldom performed and recorded by professional orchestras. We amateurs love playing this stuff, so it's an unalloyed delight to come across this exhilarating live account of the Symphony no 3. Inspired by Mendelssohn's trip to Scotland in 1829, it was completed in 1842; the murky opening supposedly prompted by a ruined chapel in the grounds of Holyrood. John Eliot Gardiner treats the symphony with respect and affection. Strings play with minimal vibrato, and winds sing out. Sample the Vivace non troppo and marvel at some effortless articulation, and at that this is one of the few performances where you can actually hear a pair of horns blasting out their semiquaver tune. The Adagio's debt to Schubert is highlighted with dark lower strings and irresistible forward motion. Mendelssohn's finale moves at a real lick – as with the last movement of the Italian Symphony, this is uniquely invigorating minor key music. When it runs out of steam, you'd be happy for the piece to close quietly, to disappear back into the mist. That triumphant coda can't help sounding like an afterthought, though Gardiner's persuasiveness makes it work.

We also get a nippy account of The Hebrides overture, and a graceful performance of Schumann's Piano Concerto from Maria João Pires. This isn't the fastest, flashiest of readings, but it's intensely musical – a wise, intelligent performance. Praise too for LSO Live's engineers – this is among the best-sounding recordings from this source. Orchestral tone is detailed but warm, and Pires is immaculately balanced. As a bonus, audiophiles get a Pure Audio Blu-ray disc containing, as a bonus, Pires's encore. For folks like me with just two ears, the hybrid SACD sounds just fine.

Don't be scared – this hour-long choral symphony with obbligato bass, setting five poems by dissident Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko is among Shostakovich's most vivid and immediate works. And this superb modern recording deserves to become a best-seller. Setting Yevtushenko's Babi Yar, a scathing denunciation of Russian anti-Semitism, inevitably caused Shostakovich difficulties. A televised relay of the 1962 premiere was cancelled, and Soviet authorities forced Yevtushenko to amend the text in the first movement, softening the poem's bite. Shostakovich didn't, however, alter the words in the score, and the bowdlerised version was quietly forgotten. Yevtushenko's texts inspired some of this composer's richest, most colourful orchestral writing, and Vasily Petrenko's performance benefits from sensational playing. The third movement's suppressed rage is chilling, and the oily tuba solo at the start of the fourth movement is the stuff of nightmares. Later on, Petrenko gives the march music real urgency; the movement's savage climax has rarely sounded so bleak.

Swift speeds give the sarcasm extra bite and point. The second movement, Humour, zips along, with raucous, idiomatic trombones. Shostakovich had a talent for spectral fadeouts, and the close of this symphony is pure magic.Yevtushenko's text makes a poignant case for honesty and integrity, and the final minutes involve a beautiful violin duet, celeste and tubular bells. Petrenko's bass, Alexander Vinograd, looks like a teenager in the CD booklet. He's fabulous – singing with absolute authority and never descending into growls. You can hear the notes, in other words. And the mens' voices? They cope heroically. They've not the characteristic sound of a Russian choir, but then they're drawn from Liverpool and Huddersfield, not Moscow. Diction is clear, and you sense that they're singing out of their collective skins. It's a masterpiece, and this recording is a fitting conclusion to one of the best modern Shostakovich cycles.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment