The lightning speed of the past, Raymond Carver once wrote. There’s no epic distance of space larger than that between the imagined futures of decades past and the way things are now. It’s the Jet-Pack conundrum: it should be here but what have we got? Drones and jogging apps.

Of course, sci-fi isn’t a literal space – or wasn’t, before CGI. It was, rather, the last trumpet of allegorical art in a world obsessed by surface images. Outside of sci-fi, we barely experience allegory in our imaginative lives. Gaming, however wacky the graphics, is about literalism and WYSIWYG shoot-ups, while most contemporary sci-fi on TV opts for literalism under a heavy glaze of soap opera plotting and character. Take the current Doctor Who and the latest assistant’s angry, emotional relationship arc with the Doctor, newly burdened with his fabled acres of darkness and loneliness, like some miserable shadow of the feature film Batman. I start to think, is this the Tardis here or are we in the fucking Queen Vic?

Current TV drama is largely preoccupied with psychopathic killers of women and children, or in the case of US mega-series such as Breaking Bad and The Wire, harking back to the triple-decker Victorian novel encompassing whole tiers of society into a satisfying morality arc. Sci-fi fares less well. Outside of US space operas, the good Doctor and Red Dwarf repeats, it is largely absent from our TV screens. And sci-fi of the grown-up, complex, dystopian and disquietingly allegorical calibre of Out of the Unknown, the groundbreaking sci-fi series from the 1960s and early 1970s, is simply, well, unknown, today.

Current TV drama is largely preoccupied with psychopathic killers of women and children, or in the case of US mega-series such as Breaking Bad and The Wire, harking back to the triple-decker Victorian novel encompassing whole tiers of society into a satisfying morality arc. Sci-fi fares less well. Outside of US space operas, the good Doctor and Red Dwarf repeats, it is largely absent from our TV screens. And sci-fi of the grown-up, complex, dystopian and disquietingly allegorical calibre of Out of the Unknown, the groundbreaking sci-fi series from the 1960s and early 1970s, is simply, well, unknown, today.

Finally released by the BFI as a DVD set this week, almost half a century after its first transmission, Out of the Unknown was the brainchild of a remarkable producer, Irene Shubik, a French-Russian émigré born in Hampstead, who worked with Sydney Newman, the flamboyant channel head who green-lit Doctor Who. As she once wrote, “good science fiction is… the nearest modern approach to the medieval romance, the fable and such satirists as Swift…” and over the three series she helmed as producer, sourcing original scripts from some of the leading sci-fi authors of the time – Azimov, Pohl, Bradbury, Ballard, Simack and more – she fashioned a 1960s sci-fi that enveloped satire, topicality and fascinating visions of future science and subjective experience as well as extreme outlandishness and characters driven by contemporary, not futuristic, complexes. Shubik stepped down from the fourth series, by now in colour, and it veered away from her brand of topical futurism into the realm of contemporary ghost story and occult drama – of which there are rich pickings in the early 1970s. In fact, these final episodes turn out to be some of the most unsettling and dystopian of the series. You weep for what was lost.

For, being cult drama from the BBC, it goes without saying that most of it was destroyed in the mid-'70s (it would be good to have that little vortex of cultural vandalism dramatised) and it is painful to watch the useful accompanying documentary that provides a few clips and stills from what appear to be some of the most ambitious productions of the whole series.

Nevertheless, this magnificent, sprawling set of seven discs features all the surviving episodes – 10 from series one, four from series two, one from series three, and five from series four – alongside reconstructions using (fan-recorded) soundtracks matched to surviving stills or, in one case, the shooting script. It’s a feast that takes time to plate up and consume, but it is rich and satisfying and you will not find it elsewhere.

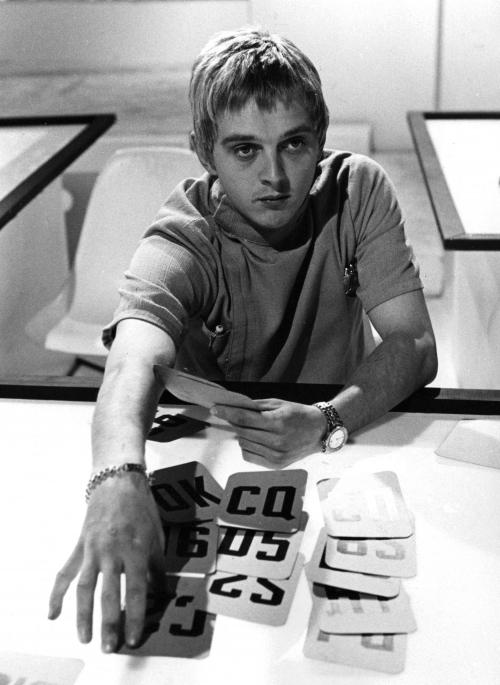

The opener to the set, an adaptation of John Wyndham’s No Place Like Earth, is slow, clunky, and old-fashioned even for 1965. This is not the case once you step further into the series, with the likes of The Counterfeit Man, starring David Hemmings, or Asimov’s brilliant The Dead Past, wherein a machine called a chronoscope uses "ancient photons" to give us magic-lantern glimpses of the past, in this case ancient Carthage. Elsewhere, time travel and a plotline that presages the Terminator trilogy makes Some Lapse in Time another stand-out. Here, the sets are by a young Ridley Scott, while the incidental music is from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, creating a sound world of musique concrète, early tape-and-scissors electronica à la Stockhausen, and pioneering, analog sound effects that are without parallel in late 20th-century entertainment and culture for atmosphere and evocation. Set these extraordinary soundscapes besides today’s scoring for Doctor Who, a tasteless synthetic sickbag of digital orchestral crescendos and multiplex detonations, and you can hear right there how digital ease led to the collapse of innovation and creativity.

As for the themes – space travel, the bomb, medicine, drugs, consumerism, spirituality, the role of the individual in a machine age – they draw deep on the stresses and conflicts of the time: the Cold War, nuclear arsenals, modern medicine, space travel, the advance of computers. From our perspective, the 1960s are often re-remembered as an era of innocence, hope, and ascendancy, but this series reveals the horror and uncertainty behind the visage.

There are strong parallels between Doctor Who under the aegis of Troughton and Pertwee and Out of the Unknown – writers, directors, stage and sound designers were shared across both serials – and both have the same derring-do of creating odd and outstanding settings and strange worlds from the simplest of means: the "tunnel under the world" in the episode of that title was made of Meccano, for God’s sake. Both series also sport the best opening and closing credits of any drama – you can’t beat the opening swirly of '60s and '70s Doctor Who, unless it’s the stark, striking chemical reactions, pre-psychedelic op art and distorted mirrors spreading across the screen for Unknown’s first three seasons.

There are strong parallels between Doctor Who under the aegis of Troughton and Pertwee and Out of the Unknown – writers, directors, stage and sound designers were shared across both serials – and both have the same derring-do of creating odd and outstanding settings and strange worlds from the simplest of means: the "tunnel under the world" in the episode of that title was made of Meccano, for God’s sake. Both series also sport the best opening and closing credits of any drama – you can’t beat the opening swirly of '60s and '70s Doctor Who, unless it’s the stark, striking chemical reactions, pre-psychedelic op art and distorted mirrors spreading across the screen for Unknown’s first three seasons.

The main difference between Who and Unknown is not only that one was more directed at families rather than adults, but that the former tended to end with closure and the triumph of good over evil, while the latter is much more equivocal. Once we get to the occult-based series four of Out of The Unknown, most of our protagonists are not only doomed but tortured, stripped and exposed before being pushed over the edge, forked and naked, into the netherworld of the series’ eerily satisfying end credits. Not even a beautiful young Lesley-Anne Down can be saved from submitting, with 50 deeply unsettling Shades of satisfaction, to rape by a restless yokel spirit in To Lay a Ghost (if the Seventies are on trial, this does not help the defence). And poor George Cole, suffering from a dual-personality invasion by an angry young man who has just blown his brains out, gets no respite from his initial act of weak-willed kindness in The Last Lonely Man.

Perhaps that’s the difference between then and now. There was enough optimism in the '60s to allow for dystopian endings that unsettled you but sent you to bed to wake into the bright fantastic tomorrow. Nowadays, you get the sense that everything is even shittier than you think it is. We can’t handle it, and allegory is too painful to consume as a result; all we want is escapism, fantasy, soap opera and stage magic. Real magic – the stuff on which dreams are made – is too hot to handle.

Perhaps that’s the difference between then and now. There was enough optimism in the '60s to allow for dystopian endings that unsettled you but sent you to bed to wake into the bright fantastic tomorrow. Nowadays, you get the sense that everything is even shittier than you think it is. We can’t handle it, and allegory is too painful to consume as a result; all we want is escapism, fantasy, soap opera and stage magic. Real magic – the stuff on which dreams are made – is too hot to handle.

- Out of the Unknown is released by the BFI

Add comment