Eric Rohmer 1920-2010 | reviews, news & interviews

Eric Rohmer 1920-2010

Eric Rohmer 1920-2010

The great French director who has died, remembered in his own words

Eric Rohmer, who died yesterday in Paris aged 89, was famed for elegant, literate, yet profoundly romantic and erotic dramas such as La Collectionneuse, My Night With Maud and Claire's Knee; and for a style that helped define the French Nouvelle Vague and that he pursued with distinction in some 50 films over the next half century (his last, The Romance of Astrea and Celadon was made two years ago).

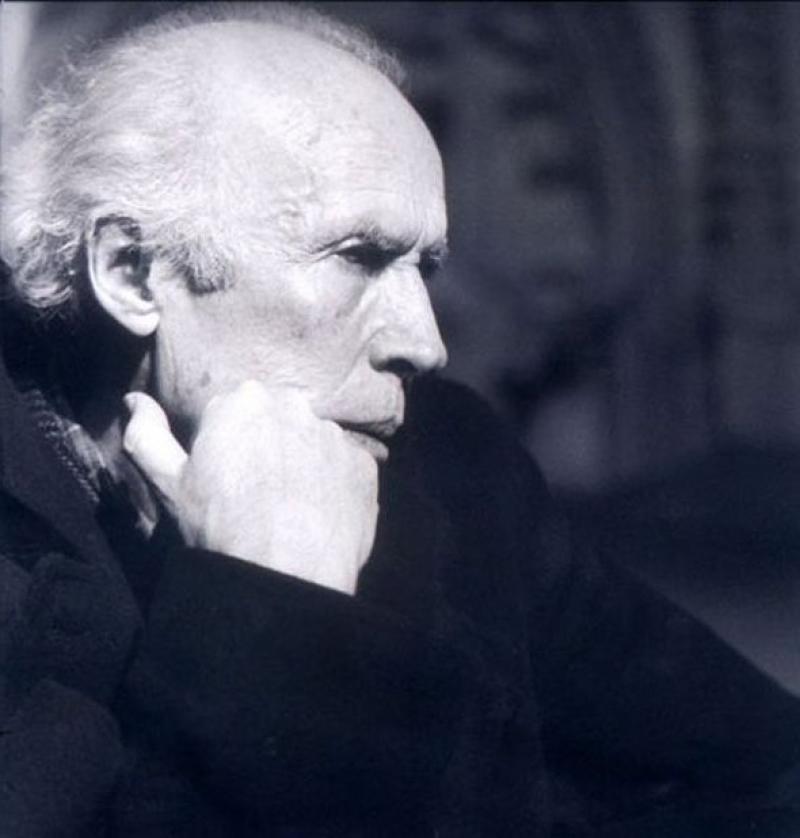

Rohmer arrives punctually in his Spartan office on the top floor of a Paris immeuble near the Museum of Modern Art. Imposing, a little gaunt, with a high domed forehead, aquiline, patrician features and large, irregular teeth, he dislikes being photographed and rarely meets journalists. In the cold midwinter light, he looks severe, ascetic and faintly sinister. He sits behind his large, tidy desk as though interviewing you for a job, and talks in French at breakneck speed as though anxious to get the disagreeable task over as soon as possible.

"No-one in France asks me about my age," says the director, then 78, rather sternly, when that subject is mentioned. And why should it be, in fact? For the past four decades, Rohmer has been steadily writing and directing films, sometimes two a year, and remains tirelessly prolific. He likes to bunch them in series: packages, as every Hollywood studio executive knows, are easier to sell and, for all his exalted reputation, Rohmer turns out, in the course of our interview, to be supremely pragmatic. Besides, to announce a future slate of four or five movies is a splendidly bullish statement of confidence in one's own longevity.

He made his name with six Moral Tales, including such Nouvelle Vague classics as Claire's Knee, My Night with Maud and Love in the Afternoon (an extract from which may be viewed above). Then came another half-dozen titles under the heading Comedies and Proverbs. In between he slipped in the odd one-off project like The Marquise of O or 4 Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle. Most recently there have been the Four Seasons. "I started out rather late," Rohmer says by way of explaining his remarkable output. "I was almost 40 when I made my first film. I have 20 years to make up."

He began as a teacher and writer. "If the cinema hadn't existed, I would have been drawn to literature. In fact, the Moral Tales were originally novellas that I couldn't get published. I don't have the stamina for a novel; the length of a film suits me better. He was also a critic and, with Claude Chabrol, his brother-in-arms in the Nouvelle Vague, wrote a hugely influential book on Alfred Hitchcock.

The contrast between the two men could scarcely be greater. Chabrol is a rotund, genial individual who laughs a lot and likes to use interviews as the excuse for a damn fine lunch. Yet his films are cruel, cynical and not infrequently bloody. "I have the impression that Chabrol [as Rohmer refers rather formally to his long-time friend] can't tell a story unless there's a crime in it. For me, it's the opposite. I have a rather optimistic temperament - optimism tempered by a little irony, because nothing in life is absolutely beautiful and successful." As our allotted hour together proceeds, the frosty exterior thaws a little. Rohmer smiles now and again; at moments he seems almost grandfatherly. At one point he does something he has always professed to abhor: he talks about a future project and, to my even greater astonishment, asks my advice about casting it [it wasThe Lady and the Duke, one of the director's one-off projects about a Scottish aristocrat, Grace Elliott, played by Lucy Russell, pictured left, who lived in Paris at the time of the Revolution].

As our allotted hour together proceeds, the frosty exterior thaws a little. Rohmer smiles now and again; at moments he seems almost grandfatherly. At one point he does something he has always professed to abhor: he talks about a future project and, to my even greater astonishment, asks my advice about casting it [it wasThe Lady and the Duke, one of the director's one-off projects about a Scottish aristocrat, Grace Elliott, played by Lucy Russell, pictured left, who lived in Paris at the time of the Revolution].

Younger, supposedly hipper directors and critics are often dismissive of Rohmer's naturalistic and apparently simple - though in fact highly sophisticated - narrative style. The director himself declines to elucidate it. "When I make a film, I have no idea of the structural pattern behind it. I know it follows a certain logic, but it's not up to me to determine it. It's up to the critics. Sometimes when I read their reviews, they help me understand my own films."

Others have pointed to the narrow range of his comfortable bourgeois world and the egocentric delusions of its characters, obsessed with the search for love and happiness. But then Jane Austen carved that narrow piece of ivory most effectively. And Chabrol once wrote an essay correctly pointing out that there is no such thing as a small subject. It's what you do with it that counts.

Yet one might have expected Rohmer, as an elder statesman of the French cinema, to be irritated or offended by these criticisms. But another surprise follows: the dispassionate candour with which he assesses his oeuvre. "I'm a director who is admired not film-by-film but for the body of his work. I wouldn't want all directors to be like each other, but there can be resemblances within your own films, as long as you don't repeat yourself. In my stories, I reprise certain themes dear to me and, in doing so, I achieve greater and truer variations by developing and deepening them than by trying to pass from one type of film to another.

"I recognise the talent of people who treat tragic subjects or who make great comedies. I admire them, but I can't do that even if I wanted to. I restrict myself to a genre which is perhaps a minor one, because I don't show big profound themes, death or suffering for instance, or important political questions, or at least only in a very allusive way.

"On the edges of my films, you can glimpse people who have trouble surviving; sometimes there is poverty. But these issues are not at the centre of the story. I feel at ease in my domain and there's no point in trying to escape it. I am what I am and I accept it. Consequently I do what I like because I like what I do." And finally Rohmer, the brilliant miniaturist, permits himself a brief laugh. "Voilà!"

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Add comment