Two rich, full December Saturdays of unsurpassable theatre, four great plays that grow more meaningful with passing time, above all supreme female teamwork to crown 2016. So Juliet Stevenson and Lia Williams playing Schiller's Elizabeth I and Mary Stuart – yes, both roles at different performances – may not be part of an all-woman cast like Harriet Walter, first among equals in the stunning Donmar Shakespeare Trilogy. Yet their collaboration is above all with each other, fusing as one person splitting apart into four distinct personalities. Only a matinee and an evening performance on the same day will give you both permutations, but it's a chance not to be missed.

For the majority who will only catch one performance, the good news is that I can't possibly say which is better. That's tantamount to declaring the real winner Schiller's magnificent, harrowingly nuanced 1800 play in director Robert Icke's adaptation, mostly faithful to the original with some trimming and the occasional updating to suit the overwhelmingly contemporary setting. No doubts here such as many had about his skewing of Aeschylus's Oresteia. While previous productions have conceded that, despite the play's title, the honours are equally divided between the two women, the line has usually been that sympathy lies with the Catholic heroine, not her duplicitous Protestant opponent. True, Harriet Walter's Elizabeth wrestled the complexity away from Janet McTeer's Mary in the last major London production, but Icke's vision is the first to suggest that more connects these strong women in their struggle against the world than separates them in terms of outward position. The very opening (pictured above) is gripping: the two women come down the two aisles, stylishly dressed in suits and open-necked shirts, and the character who's to be torn between them, sexy opportunist Leicester (John Light), spins a coin. Screens allow us to see which way it lands: unknown to the two main actors until it settles, at every performance except the second of two on the same day. Saturday's matinee gave us Williams as Mary, Stevenson as Elizabeth; the evening went through the same coin-spinning ritual, but only for show, with no-one choosing, and heads as the foregone conclusion.

The very opening (pictured above) is gripping: the two women come down the two aisles, stylishly dressed in suits and open-necked shirts, and the character who's to be torn between them, sexy opportunist Leicester (John Light), spins a coin. Screens allow us to see which way it lands: unknown to the two main actors until it settles, at every performance except the second of two on the same day. Saturday's matinee gave us Williams as Mary, Stevenson as Elizabeth; the evening went through the same coin-spinning ritual, but only for show, with no-one choosing, and heads as the foregone conclusion.

Even at the first of the two performances, I could hear inflections personal to each actor in the other's voice, showing how close they had come in this unique synthesis; but only the second highlighted the differences, which are to be treasured rather than used against either performer. Williams is lithe and sensual; her Mary uses the power of seduction – clearly the real-life Queen of Scots's strongest asset from her pampered French youth, though not a necessity at the end of her long imprisonment – to try and score points off the men who hold her fate and the keys to her imprisonment. Williams's Elizabeth is far more kitten-into-tiger with the men of her court; Stevenson's English Queen starts with monumental fixity, but stalks like a caged animal within the ring of male courtiers who in another sense hold her captive. Her Mary sears the soul with delirious poetic celebration of her brief time outdoors at Kenilworth.

The difference, in short, is between a potential Cleopatra (Williams) and the eloquence of Portia (or Isabella in Measure for Measure, one of Stevenson's most compelling roles at the RSC over 30 years ago). Stevenson is arguably the finest verse-speaker of the English language – "arguably" meaning I think so – with the widest range, but Williams is different in her soft-spoken beauty and perhaps more real in her extreme rage. If Stevenson is more theatrical and Williams more actorish, that's not a negative criticism either. The crucial confrontation at Kenilworth Castle which never happened in real life (pictured above with Williams as Elizabeth, Stevenson as Mary), Schiller using dramatic supremacy to seal essential truths, has the women on different sides in each version (symmetries which will only be recognised by anyone who sees both casts). Stevenson's Queen is terrifying in her stony implacability; Williams's allows the vulnerability to show sooner. It's Schiller's genius not to let the action fall off after this point – after the interval, in this production. In both versions, the true-to-life prevarication of Elizabeth over signing Mary's death warrant makes us hold our collective breath, and Mary's dignity and victory in accepting the outcome moves us to tears.

If Stevenson is more theatrical and Williams more actorish, that's not a negative criticism either. The crucial confrontation at Kenilworth Castle which never happened in real life (pictured above with Williams as Elizabeth, Stevenson as Mary), Schiller using dramatic supremacy to seal essential truths, has the women on different sides in each version (symmetries which will only be recognised by anyone who sees both casts). Stevenson's Queen is terrifying in her stony implacability; Williams's allows the vulnerability to show sooner. It's Schiller's genius not to let the action fall off after this point – after the interval, in this production. In both versions, the true-to-life prevarication of Elizabeth over signing Mary's death warrant makes us hold our collective breath, and Mary's dignity and victory in accepting the outcome moves us to tears.

Are there weaknesses? Only in the two women's scenes with some of the men (Schiller in his concern for psychological truth across the board has given everybody something interesting to do or be). Rudi Dharmalingam's young conspirator Mortimer is the weakest link: too staccato and short-winded in some of his speeches to be credible. I was prepared to declare Elizabeth's first scene with Leicester unconvincingly sexed-up by Icke until I saw it played out between Light and Williams, a more supple physical performer than Stevenson. Vincent Franklin's inexorable figure of anti-Catholic vengeance Burleigh (aka Cecil, pictured below on the left with Light, Daniel Rabin as Kent and Stevenson as Elizabeth) was stronger in the evening performance. Utterly consistent, on the other hand, were Sule Rimi's incorruptible jailer Paulet, Alan Williams's father-figure Talbot and the deftly-suggested cameos of tragicomic fall-guy Davison (David Jonsson) and French ambassador Aubespine (huge promise from Alexander Cobb). Mary's lifelong nurse Hannah Kennedy gets the most dignified, touching of portrayals from Carmen Munroe (no passive servant, this one) and Mary's last scene is enriched both by the rosy-cheeked RADA student handmaidens and by true Scot Eileen Nicholas as Melville. If you don't know the play you wonder whether there really was a break with precedence in a female Catholic priest, and even if you do the uneasy question of how impossible it is now intrudes. But point taken: Icke wants Mary's spiritual victory to be flanked only by women.

Mary's lifelong nurse Hannah Kennedy gets the most dignified, touching of portrayals from Carmen Munroe (no passive servant, this one) and Mary's last scene is enriched both by the rosy-cheeked RADA student handmaidens and by true Scot Eileen Nicholas as Melville. If you don't know the play you wonder whether there really was a break with precedence in a female Catholic priest, and even if you do the uneasy question of how impossible it is now intrudes. But point taken: Icke wants Mary's spiritual victory to be flanked only by women.

The honours of the final goings-beyond are shared by Schiller on the one hand – his genius is to show us Elizabeth in final, total isolation – and Icke along with his production team on the other. Designer doyenne Hildegard Bechtler has found virtue in simplicity until the one design coup, which I won't spoil, culmination to a sound-and-movement wonder which substitutes for the final soliloquy Schiller gives to Leicester. And if the ever-present soundscape, peerlessly executed as ever by Paul Arditti, mildly irritated me on the first viewing, and seemed more admirable on the second, Laura Marling's climactic song is just beautiful; the silent background thereafter is all the more devastating.

So yes, towering performances from the leading ladies, discombobulating to the point of feverish obsession when you see each take on both queens (and when it comes to awards, they'd have to share it), but this is definitely not just star performers' theatre in the usual British style. The whole is so much more than the sum of its parts, and a shattering experience.

ROBERT ICKE: HIS CAREER SO FAR

ROBERT ICKE: HIS CAREER SO FAR

Boys. Ella Hickson’s new play is fuelled by testosterone but floats on nuance

Mr Burns. A startling vision of a post-apocalyptic world dominated by The Simpsons

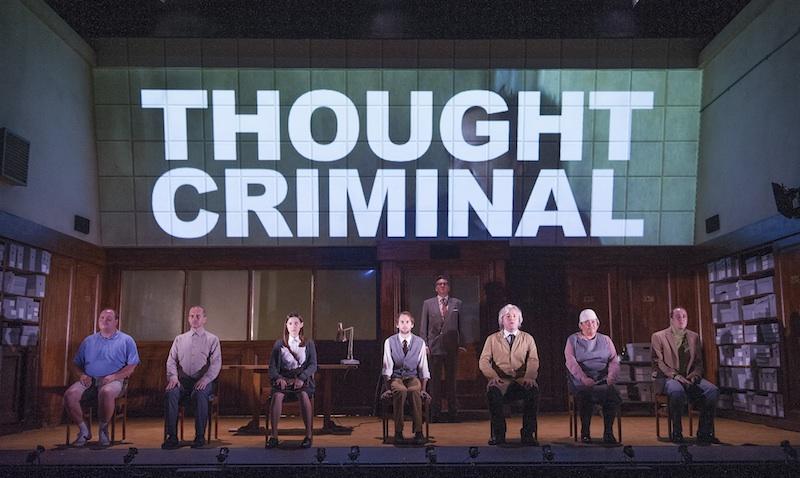

1984 (pictured by Tristram Kenton) Headlong's adaptation of George Orwell's novel is a theatrical coup

Oresteia. Lia Williams stands firm on the bones of Aeschylus in uncertain makeover

Uncle Vanya. Robert Icke's lengthy revival/reappraisal is largely a knockout

The Red Barn. David Hare’s latest is a superb adaptation of a Simenon thriller

Hamlet Predictably unpredictable performance from Andrew Scott subject to Icke's slow-burn clarity

Add comment