Picasso: Minotaurs and Matadors, Gagosian | reviews, news & interviews

Picasso: Minotaurs and Matadors, Gagosian

Picasso: Minotaurs and Matadors, Gagosian

Bullish Picasso still fascinates in Sir John Richardson’s richly curated show

At 93, Picasso’s revered biographer, Sir John Richardson, has curated a vital new celebration of the artist’s life and work, focusing on one of his most enduring and delightful subjects, the Minotaur.

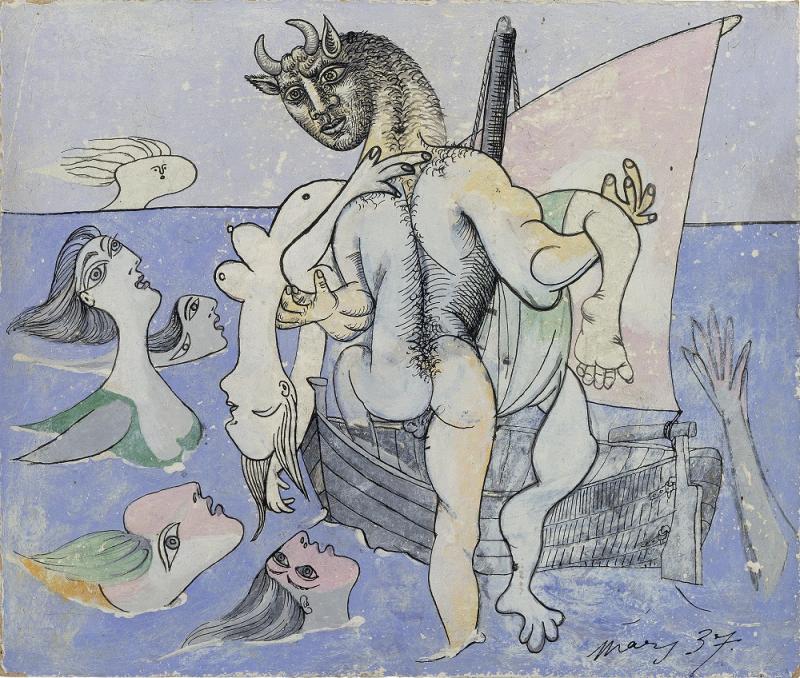

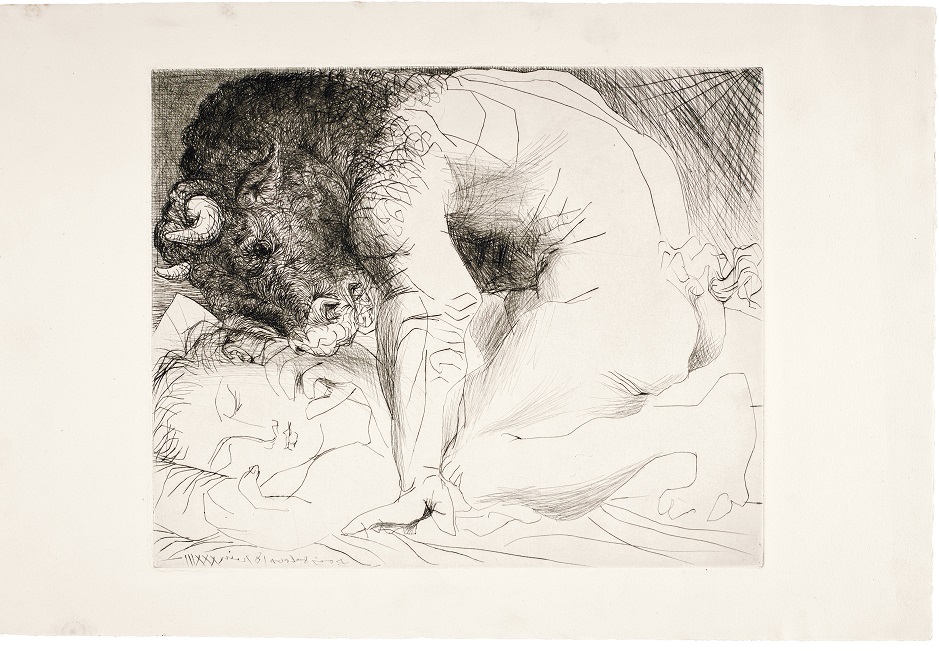

Born in Málaga in Spain, Picasso had grown up fixated with the drama of the bullfight and the Mediterranean culture of the bull; so when the Minotaur emerged as a key surrealist symbol in the 1930s (following Evans’s amazing archaeological discoveries in Knossos, Crete), it was a natural theme for him to explore. But it is the intersection of ancient mythology with Picasso’s bullfighting and biographical imagery (often depicting his family, wives and mistresses) that provides particularly rich material for Richardson. (Pictured below: Minotaure caressant du mufle la main d’une dormeuse, June 18, 1933, Boisgeloup) For the Surrealists, the Minotaur perfectly encapsulated the human condition. Picasso, however, brings a more personal element to bear: he really saw himself, as Richardson explains, as something of a monster, while also priding himself on his great creative power and sexual prowess: “the ‘god-like’ Minotaur was made for him.” Picasso’s own observation serves as a further rationale for the exhibition: "If all the ways I have been along were marked on a map and joined up with a line," he memorably said, "it might represent a minotaur."

For the Surrealists, the Minotaur perfectly encapsulated the human condition. Picasso, however, brings a more personal element to bear: he really saw himself, as Richardson explains, as something of a monster, while also priding himself on his great creative power and sexual prowess: “the ‘god-like’ Minotaur was made for him.” Picasso’s own observation serves as a further rationale for the exhibition: "If all the ways I have been along were marked on a map and joined up with a line," he memorably said, "it might represent a minotaur."

Picasso is, of course, also the Matador – wielding his paintbrush, as one writer memorably put it, “like a sword dipped in the blood of all the colours” (Rafael Alberti, 1969). The earliest picture in the show is of a little Picador (1889) – made when Picasso was seven – illustrating his life-long interest in the heroes of the bullring. An unusually melancholic sculpted head of a matador with a broken nose reveals the human cost, but there is little hint of this in the joyous and gaudy portraits of Picasso’s much later matadors and toreros of the 1970s, with their brilliant capes of bloodied red.

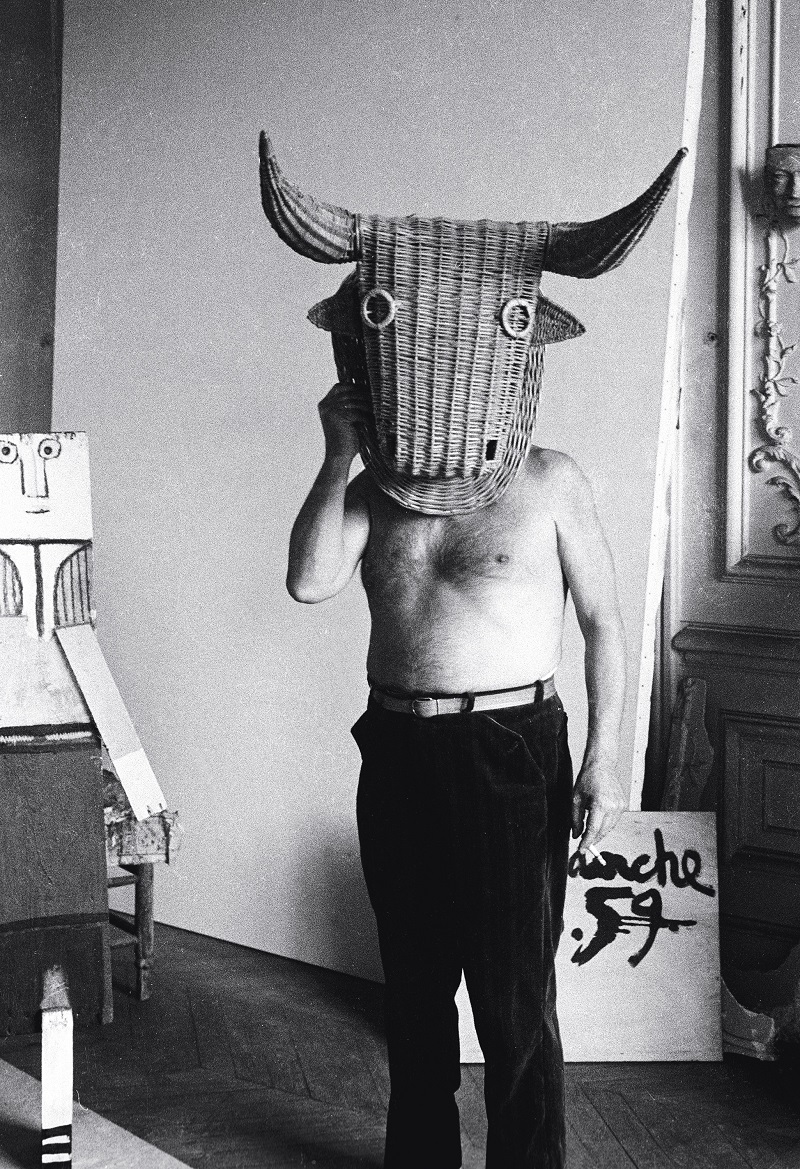

Then there is the great bull itself – heavy, lumbering and immensely potent, or an ancient sacrificial offering, its lethal horns often balanced on its huge broad head like a slender crescent moon. A suite of wonderful lithographs of 1945 explores the animal’s awesome form, deconstructing it and finely paring it down. Another marvellous series graphically portrays the death of a matador, with the bull’s fury expressed in a flurry of ferocious, urgently drawn lines. In a cluster of bull portraits, we sometimes see the dark eyes of the artist staring out at us, vaguely amused: now Picasso has become the Minotaur (in one photograph he stands, with naked torso, balancing a wicker mask of a bull in front of his face). Here he is bestial and brutish in appearance, but also human and playful. (Pictured above: Picasso with a bull’s head mask,

Then there is the great bull itself – heavy, lumbering and immensely potent, or an ancient sacrificial offering, its lethal horns often balanced on its huge broad head like a slender crescent moon. A suite of wonderful lithographs of 1945 explores the animal’s awesome form, deconstructing it and finely paring it down. Another marvellous series graphically portrays the death of a matador, with the bull’s fury expressed in a flurry of ferocious, urgently drawn lines. In a cluster of bull portraits, we sometimes see the dark eyes of the artist staring out at us, vaguely amused: now Picasso has become the Minotaur (in one photograph he stands, with naked torso, balancing a wicker mask of a bull in front of his face). Here he is bestial and brutish in appearance, but also human and playful. (Pictured above: Picasso with a bull’s head mask,

Golfe-Juan, Vallauris, France, 1949. © edwardquinn.com)

Some of the most glorious works in the show explore the Minotaur’s love of women and his ravenous sexual appetite, or the reverent relationship between the hairy beast and his nude female model. We see the Minotaur contemplating female beauty, being both majestic and celebratory, but we also see him becoming the hideous violent aggressor. Picasso clearly regarded the Minotaur as a Dionysian, satyr-like creature – in some works satyr and Minotaur fuse - but he also connects its death (from a mortal knife-wound inflicted by the hero Theseus) to the ritual slaying of bulls in the ring. (Pictured below: La Minotauromachie VII, 1935, Paris) At turns comic, tragic and violent, the Minotaur also reflects Picasso’s reactions to the political upheavals of the time, containing hints of suffering, menace and deep cruelty. There is also a more explicit autobiographical element to some of the works. The starting point for the exhibition was Richardson’s essay in the New York Review of Books, which ties the imagery of the great series of etchings La Minotauromachie (1935) – displayed along one wall of the exhibition – to a traumatic episode in Picasso’s youth (a broken vow he made to his sister Conchita, who died at the age of seven). The artist’s grandson, Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, was so inspired by Richardson’s interpretation, that he suggested this exhibition as a means of continuing the process of uncovering ever richer insights.

At turns comic, tragic and violent, the Minotaur also reflects Picasso’s reactions to the political upheavals of the time, containing hints of suffering, menace and deep cruelty. There is also a more explicit autobiographical element to some of the works. The starting point for the exhibition was Richardson’s essay in the New York Review of Books, which ties the imagery of the great series of etchings La Minotauromachie (1935) – displayed along one wall of the exhibition – to a traumatic episode in Picasso’s youth (a broken vow he made to his sister Conchita, who died at the age of seven). The artist’s grandson, Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, was so inspired by Richardson’s interpretation, that he suggested this exhibition as a means of continuing the process of uncovering ever richer insights.

The installation, designed by Caruso St John (the modernist architects of the Gagosian), creates dimly lit rooms, which with their green pleated curtains, plywood trestles (and even the odd bit of hessian) hark back to the 1950s era. This period feel is enhanced by the image at the entrance to the show – a striking bull "self-portrait" of 1958. With its fine array of ceramics, paintings, lithographs, sculpture, etchings, the exhibition is also a reminder of Picasso’s career-spanning versatility and brilliance – even the few uneven works have a bullish confidence that wins through.

- Picasso: Minotaurs and Matadors at the Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill until 25 August

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment