Michelangelo: Love and Death review - how to diminish a colossus | reviews, news & interviews

Michelangelo: Love and Death review - how to diminish a colossus

Michelangelo: Love and Death review - how to diminish a colossus

Earnest and worthy cinematic documentary fails to bring the glorious artist to life

As perhaps the greatest artist there has ever been – and as one of the most fascinating and complex personalities of his era – Michelangelo should be a thrilling subject for serious as well as dramatic cinematic documentary treatment.

The title Love and Death suggests that these will be the potent twin themes of a new biographical and art historical approach. But the result, I’m afraid, is reverent and terribly dull and doesn’t begin to get under the skin of its sensational subject.

Shot in ultra HD 4K, Michelangelo - Love and Death also promises “unprecedented up-close access to the artist's blockbuster works”, and atmospheric shots of Florence, Rome and Carrara that will transport us to Michelangelo’s Renaissance Italy from the comfort of a local cinema. As someone who has written about Michelangelo, and who was looking forward to wallowing in the 4K experience of his work (which is often on such a colossal scale that it cannot be fully comprehended by the naked eye), I expected to be blown away by the sensory experience alone. (Pictured below: Michelangelo's David, Accademia) But although there is grandeur, the shots are for the most part limited and executed in the style of the 50-year-old landmark Civilisation documentary. Sculpture and fresco in situ are often rendered flat by being shot mostly from one angle. Particularly poor are the sections on the Sistine Ceiling and the Last Judgment frescoes – where we are presented with long tracking shots and dull explanations of the iconography instead of telling close-ups and an explanation of the beauty and originality of Michelangelo’s highly personal conception.

But although there is grandeur, the shots are for the most part limited and executed in the style of the 50-year-old landmark Civilisation documentary. Sculpture and fresco in situ are often rendered flat by being shot mostly from one angle. Particularly poor are the sections on the Sistine Ceiling and the Last Judgment frescoes – where we are presented with long tracking shots and dull explanations of the iconography instead of telling close-ups and an explanation of the beauty and originality of Michelangelo’s highly personal conception.

What we are, in effect, treated to is an old-fashioned linear film that is incredibly slow - with long soporific mixes from one image to another instead of energetic editing. A device with a mature good-looking Italian sculptor hammering away at marble, causing chips to fly, is no doubt intended to give us a sense of the physicality of Michelangelo’s sculptural approach. It is intercut throughout the film, eliminating the impact of his precocious youthful achievements (with many masterpieces achieved by the time he was 30) and failing to evoke Michelangelo’s terribilità (terrifying force). We are told that Michelangelo’s ideas emerge fully formed from the marble, that his masterpieces are just waiting to be revealed; but one of the most remarkable things about Michelangelo’s process was his intellectual experimentation; his ability to modify and take hair-raising risks as he went along.

The film attempts to be comprehensive and authoritative, peopled with reputable talking heads like critics Martin Gayford and Jonathan Jones and Vatican Museum and National Gallery curators. Those that are knowledgeable are fairly dry, but reliably informative; others, who valiantly attempt to inject some drama into the proceedings, too often fall into the trap of mythologising the “lone” genius (we know, for instance that Michelangelo worked with a number of assistants throughout his career) or resorting to talking about “sexy” nudes. Often the interviews have the feeling of a first cut, with hesitations left in. Renaissance madrigals and an Italian actor, whose portentous reading of Michelangelo’s poetry nulls the meaning of the words, add to the growing irritation.

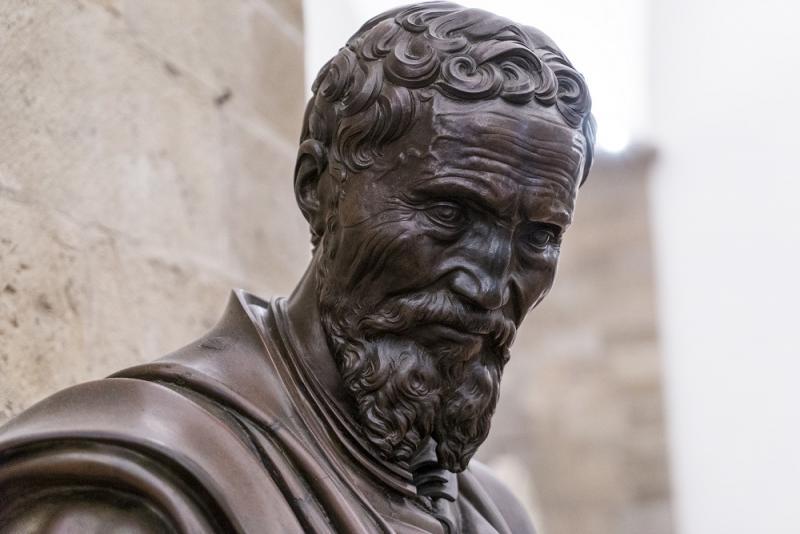

Quotations from contemporary biographers, Vasari and Condivi, are used as narrative devices to take us roughly chronologically through Michelangelo’s oeuvre. Because there are so many works to cover, we are given very little of the all-important context that Michelangelo was operating in: two of the most salient features of Michelangelo’s life and the driving force of his art is his jealous rivalry with other artists and his complex familial relationships; but the list approach, which dutifully plods through most of the key works and locations, ensures that what drama there could have been is lost. The film spends too long on the first third of Michelangelo’s life and peters out at the end, missing out the stunning masterpiece of Michelangelo’s final years – the Rondanini Pietà – and barely touching on the enigma of his huge number of unfinished marbles (26 out of 43). Too much time is given over instead to two newly anointed Michelangelo bronzes (pictured above) in the Fitzwilliam Museum (their attribution to Michelangelo is hotly contested by some leading Michelangelo scholars), two presentation drawings in the Royal Collection (with a pedestrian explanation of their iconography), and plaster casts in the V&A, betraying the film’s British bias. In this context, it is rather surprising that the Royal Academy’s Michelangelo – the Taddei Tondo – is not included, along with the other great Michelangelo tondos in Florence.

The film spends too long on the first third of Michelangelo’s life and peters out at the end, missing out the stunning masterpiece of Michelangelo’s final years – the Rondanini Pietà – and barely touching on the enigma of his huge number of unfinished marbles (26 out of 43). Too much time is given over instead to two newly anointed Michelangelo bronzes (pictured above) in the Fitzwilliam Museum (their attribution to Michelangelo is hotly contested by some leading Michelangelo scholars), two presentation drawings in the Royal Collection (with a pedestrian explanation of their iconography), and plaster casts in the V&A, betraying the film’s British bias. In this context, it is rather surprising that the Royal Academy’s Michelangelo – the Taddei Tondo – is not included, along with the other great Michelangelo tondos in Florence.

As the film ambles towards its abrupt conclusion – the death of Michelangelo announced in caption – one feels that the director has run out of puff and is regretting the fact that Michelangelo lived for 89 years and enjoyed a career that spanned more than 60 years and many media. It is not enough to hail this film as a worthy endeavour because of its art subject. Cinematic documentary-making has moved on and art history is an alive and buzzing discipline that deserves more dynamism, humour and insight.

- More film reviews on theartsdesk

- Alison Cole is the author of Michelangelo Buonarroti: The Taddei Tondo (Royal Academy Publications, £12.95)

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

An excellent review of an