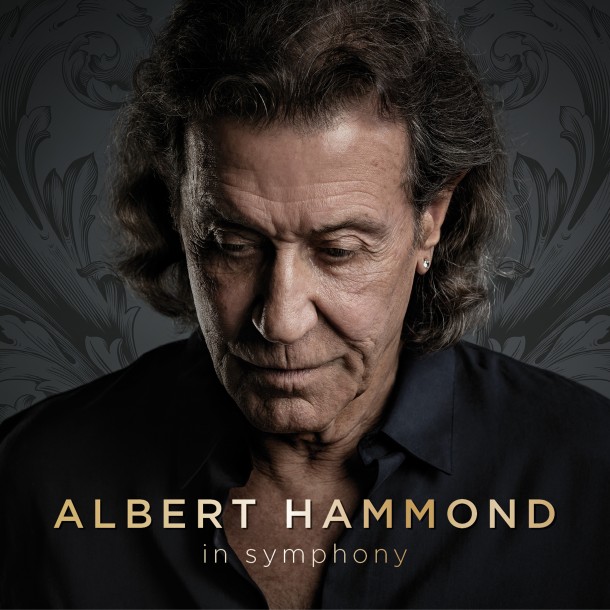

Albert Hammond might not be a household name but he's still, undeniably, one of the world's greatest living songwriters. His songs have sold 360 million copies, ranging from Starship's soft-rock classic "Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Now" to Julio Iglesias' "To All the Girls I've Loved Before". Hammond's own singing career includes "It Never Rains in Southern California", and last June he released In Symphony – a career retrospective arranged for voice and orchestra. On September 19 he will be performing these arrangements at London's Cadogan Hall.

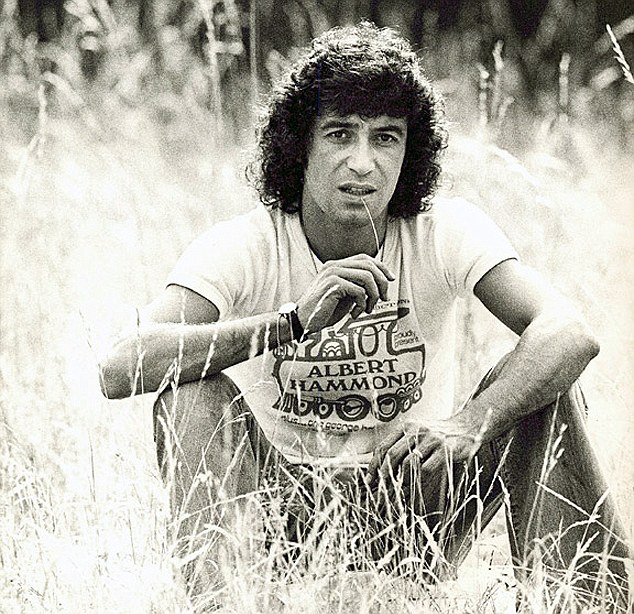

Hammond was born in London in 1944, his family having been evacuated from Gibraltar. After the war, they returned home, and as a boy, Hammond would listen to a huge variety of music – from rock'n'roll to flamenco. Later, he taught himself to play guitar and formed a band, The Diamond Boys.

Hammond was born in London in 1944, his family having been evacuated from Gibraltar. After the war, they returned home, and as a boy, Hammond would listen to a huge variety of music – from rock'n'roll to flamenco. Later, he taught himself to play guitar and formed a band, The Diamond Boys.

After winning a Spanish songwriting contest Hammond relocated to London to try and make a living as a writer-for-hire. Initially, work was slow and he supplemented his earnings by washing dishes in the Chelsea Drugstore. But after teaming up with fellow songwriter Mike Hazlewood his career took off.

During the early Seventies, Hammond and Hazlewood had a string of hit singles including "The Air That I Breathe" which became a massive hit for the Hollies. Throughout his career, Hammond has continued to partner with some of the world's most successful songwriters, including Dianne Warren, Hal David and John Bettis. Together they have written songs for artists including Whitney Houston, Tina Turner, Leo Sayer and Diana Ross. Younger music fans may know Hammond better as the dad of Albert Hammond Jr, guitarist with the Strokes, or through his work with Duffy.

I call Hammond on the phone from London. He is up in the mountains near Malaga in Spain working on a musical about Edward Whymper, the mountaineer who conquered the Matterhorn. There is a 48-degree heatwave in Spain, but Hammond says being so lean and wiry, the heat doesn't bother him too much. His conversation is brimming with enthusiasm and excitement. It makes me wonder how much this natural energy has helped his remarkable career.

RUSS COFFEY: You've been making your living writing songs for almost 55 years – what is the secret of such a long career?

ALBERT HAMMOND: I imagine it's love and passion for the music and the privilege of having been given a gift to write music that millions of people love. I was never interested in money – that's not my motivation. My motivation is just to write some wonderful music and try to better myself.

ALBERT HAMMOND: I imagine it's love and passion for the music and the privilege of having been given a gift to write music that millions of people love. I was never interested in money – that's not my motivation. My motivation is just to write some wonderful music and try to better myself.

Perseverance has had something to do with it – I never gave up. But I don't really have to work on writing songs – they just come to me. It just feels right. And I do it quickly. It's very from the heart. I don't have a way of writing, but I am inspired by conversations and words and actions and movement and that kind of stuff – so maybe that's a way of writing?

I've worked with a lot of people who have formulas, almost like "Oh, you remember that song from the Sixties – it had these four chords?" Everybody's different. I couldn't write a book about how to write songs because I just don't know how I do it.

On your latest album you have re-recorded many of your greatest hits with an orchestra – was this a long held ambition?

It's something I've had in mind for the last 15 years. Obviously, I was wondering who might give me the money. But I was patient enough and got lucky. I was performing a show and the right people were there watching. They were from a record company and came backstage and said, "We love what you did – would you like to make a record?" and I said, "There's only one record I would like to make and it's with a symphony orchestra!"

I used to do rap in the Sixties. Mike Hazlewood and I wrote a few rap songs in the Sixties where we actually rapped

Do you think there's something special about that sound, that orchestral pop sound, that transcends physical age and culture?

I didn't want to sound like I was trying to be 20 years old because I'm not. I'm 73. The reason I said I would love to do a symphonic album was because I had this idea to sit down with an arranger and tell him – "Let's think about how the great classical writers would have arranged these kinds of songs." A song like "One Moment in Time" [performed by Whitney Houston] could have been written by one of the classics because it's got that kind of a melody.

When we made the record, I would ask, "What do think Beethoven would have done with what I've written?" We spent over a month going through the arrangements, and I think the result is a classic record, with some classic songs.

Is it true that being a limited musician made you a better songwriter, and do you think too much technology is a problem for today's musicians?

There's a lot of great musicians who can't write a song. For me it was all about discovery – I would put my fingers on the piano or on the guitar and I'd put my fingers on a strange place and I'd play what I thought was a chord and it inspired me to write a song because of the sound I'd discovered. When I made the record and talked to the musicians,they would say that's a G Maj 7 over 9th. and I'd go, "Really, is that what's it's called?"

When you don't know enough chords you can only play what you know and your melodies still go all over the place. They go up and they go down and they rub against the chords and that makes a big difference too.

I think the problem for today's musicians is that they kind of write a little piece and then they leave it to the side and then they write another little piece another day, and then it's like a jigsaw puzzle. They don't write a full song. When I write, I will play my acoustic guitar and sing two verses, a chorus, a bridge and two choruses to go out. A whole song.

My son also writes in pieces and it's a way of doing it, obviously. But I just don't know how to do it that way. I can only do it the way I do it.

Albert Hammond performs "It Never Rains in Southern California"

Talking of your son [Albert Hammond Jr, guitarist for the Strokes], do you guys ever play together?

No, we've never really played together, and we've never written. We did a duet about four years ago. I was doing a record of duets. I sent him this new song I'd written and he played the guitar and sang with me. But generally, I let him do his own thing.

Did you teach him?

I taught him three chords. When he was nine years old, we were in London and I took him to see The Buddy Holly Story. It was playing in the Victoria Palace and I told him, "I'm going to take you to a theatre where I performed in the 70's and we are going to see the story of my idol." I'm doing what I'm doing because of Buddy Holly. And after the show, he said to me, "Dad, can you teach me three chords like you learned and maybe I can play some Buddy Holly songs?"

Who would be on your top list of younger musicians to collaborate with?

The one I really like a lot is Justin Bieber. I like his style, I like the way he sings. To me, as a young kid, he also reminds me of a young Elvis. Did you know Elvis was blond by the way – he dyed his hair. I would say if I collaborated with someone like Justin Bieber, it would be great.

Would you ever consider taking part in a rap project?

I used to do rap in the Sixties. Mike Hazlewood and I wrote a few rap songs in the Sixties where we actually rapped. I think PJ Proby did a song called "Empty Bottles'". There was a singing chorus but the verses were rapped. There was another song that went [Hammond starts rapping], "There were eight in the room with the cigarette cloud /And we got the record player play the records real loud/ And the racket could be heard all over the town/ And we're going to keep it cool until the house falls down."So we used to do those things, yeah.

You just mentioned your work with Mike Hazlewood. Why is it that songwriters often find it easier to write in a partnership?

I don't know if it's that they find it easier. It's more that it's really lonely to write on your own and songwriters are all very insecure. After I stopped working with Diane Warren every time she wrote something she would call me and say, "Hey, what do you think of this?' and I would give her my vibe. We're all insecure in some way, and when you write with somebody you've got that mirror, you've got that bouncing board on both sides, musically and lyrically. But to write with people you've got to have the chemistry between you.

Albert Hammond and Dianne Warren's "Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Now" performed by Starship

You've lived all over the place – Gibraltar, Spain, England, the States – where is the best place to live and where do you call home?

I don't have a home now. I'm touring all the time. In fact, I left LA in January, and I don't know when I'll go back but I can't go back before February of next year. I would say my home is a hotel room.

The best place to live? There are many great places. I tell you what, I wouldn't give up my childhood in Gibraltar. Part of who I am is where I grew up and who my parents were. Just two humble people and not rich. My father was a fireman and my mother was a housewife, and I stayed with their values ever since. It just feels good to be the way I am.

Is it true that you have another career in Spanish that most of your English speaking fans don't know about?

Yeah. I have as big a career in the Spanish market as I do in the English market. I've written hits for all kinds of huge acts and recorded many hits myself. I also did the Latin Aid for Africa record – Cantaré Cantarás, which I recorded in 16 hours.

I picked up the Latin sound in Gibraltar. That's why I said I wouldn't change living in Gibraltar for anything because I heard every kind of music there. In Gibraltar, I heard all the pop and rock and rhythm and blues and country and jazz and everything from the juke boxes in the pubs. Morocco was only a boat's ride away and in half an hour you had the Arabic music. I could also hear flamenco and all kinds of Spanish music. And my father used to love opera which he played on Sunday mornings. I think that's why I have written songs in so many different genres. I've had hits in the R'n'B market, in the country market, the pop market, the rock market – from Aretha Franklin to Steppenwolf, to Johnny Cash, to Julio Iglesias, to Tina Turner.

Which styles resonate with you most? Some of your songs – like "Don't Turn Around" have been recorded in several styles.

Yeah, I have recorded it myself on this record. The fact Ace of Base did it the way they did it and Aswad did it in a reggae style – thank you very much, what can I say? But I don't have a preferred style. I think that music is music. I would love to write classical music one day. I'm not going to write the notes but I'm going to sing it. There's a lot of classical and marches in my Matterhorn musical.

Can you tell me what the Matterhorn musical is about?

Can you tell me what the Matterhorn musical is about?

The musical is based on the Matterhorn, which is the story of Edward Whymper, an Englishman who was the first to climb to the top. The idea behind it is really humans against nature.

When we put together this story we felt that the mountain was nature and humans were trying to conquer it and destroy it. In the end, we make the mountain actually a woman, that throws rocks down and never lets people climb to the top.

It's 1865 when this happened and the Matterhorn was a virgin mountain. Edward Whymper wasn't actually a mountaineer, he was a sketcher. In those days people would sketch just to get a picture. He fell in love with this mountain and soon it became something more because he was in love.

The project came about because a German writer called Michael Kunze came to see one of my shows and said he'd like to work with me. I said "find a project", so he came up with the Matterhorn. We have developed it with the director Shekhar Kapur, who recently did a thing on William Shakespeare called Will. The orchestrating is being done by an American arranger and a Dutch arranger who I am up in the mountains with now (pictured above). The style of music is everything from rock to pop to classical to marches.

When do you think you might finish it?

Well, it's actually finished. Even though a musical is never finished. It will open in St Gallen in Switzerland next February. We thought we'd open there, plus the producers are from there and then we will invite people from other parts of the world to come and see it.

Now you have done a musical do you have any ambitions left over?

Ambitions? You know I am a dreamer so I always dream of new things. One of the things I always dream of is that I don't think I have written my best song yet, so I keep dreaming that I have a better song in me.

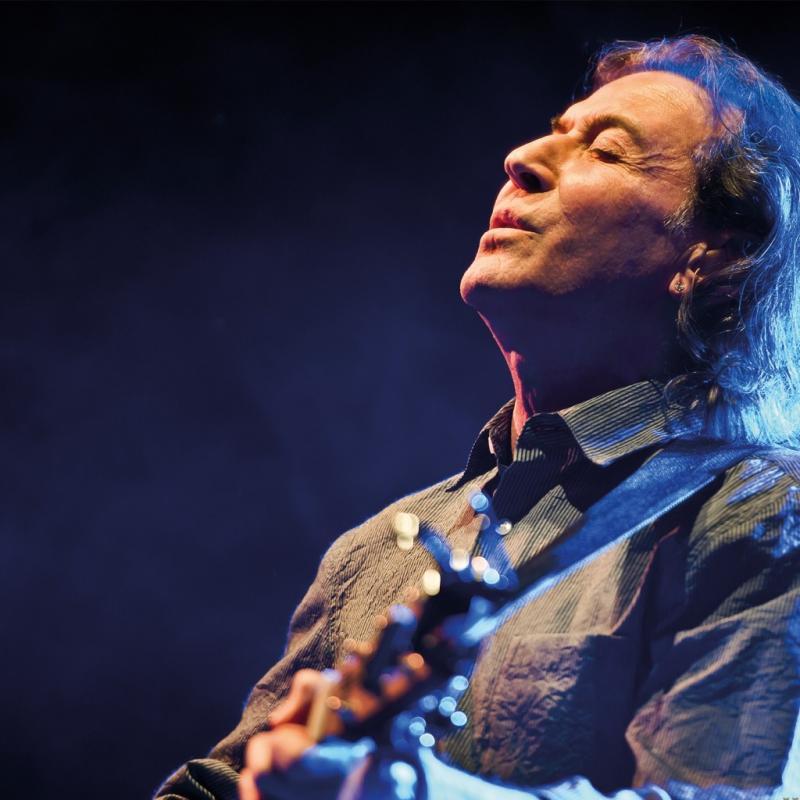

Finally, there's a concert coming up in London on Sept 19 – what can we expect?

I am doing two shows outside of Germany/Austria/Switzerland, with the Leipzig Symphony Orchestra. One in Dublin on the 16th of September and the other is in London on the 19th. Along with the Leipzig Symphony Orchestra, we will have a six- or eight-piece choir with me, so we will be 70 people travelling. It's the first time I will take that many people with me on the road. I doubt I am going to make any money. I'm probably going to lose some money but I want to do it. I think it would be a great achievement.

People can expect a two-hour show of beautiful songs that will take people through five decades to the soundtrack of their lives and more, too. It will be a wonderful evening of music played by a beautiful orchestra and they can even join in singing and clapping.

Add comment