Peggy Seeger: First Time Ever - A Memoir, review - a remarkable life | reviews, news & interviews

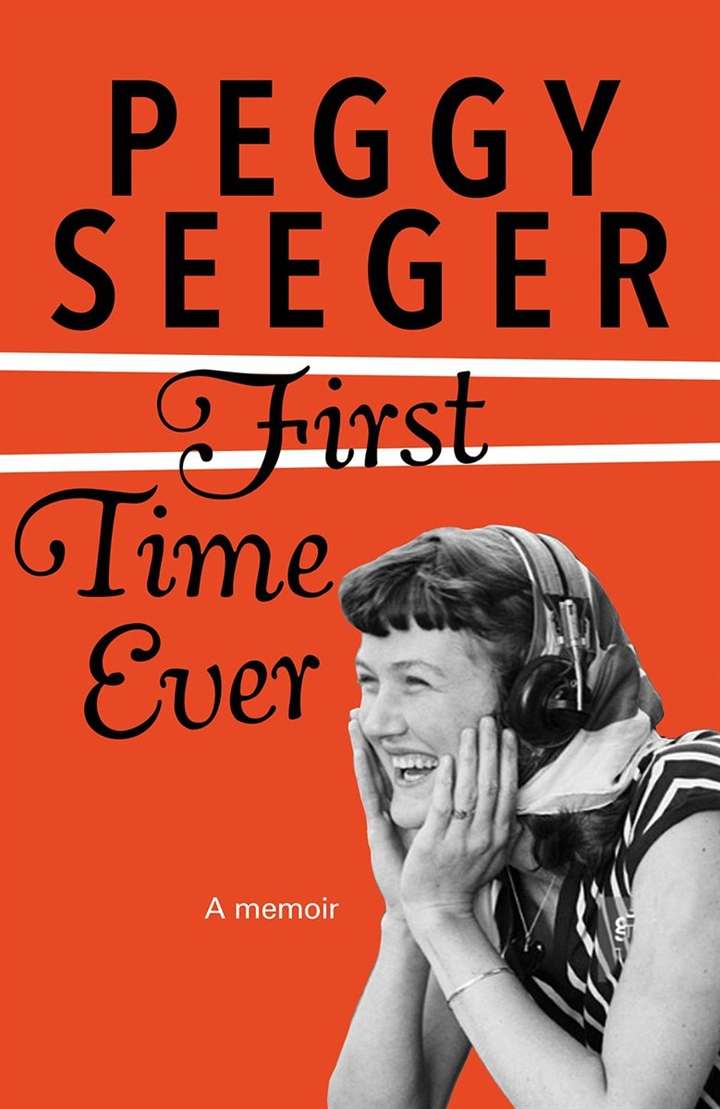

Peggy Seeger: First Time Ever - A Memoir, review - a remarkable life

Peggy Seeger: First Time Ever - A Memoir, review - a remarkable life

Folk clubs and abortions: the American singer tells of life with Ewan MacColl

Seeger. A name to strike sparks with almost anyone, whether or not they have an interest in folk music, a catch-all term about which Peggy Seeger and her creative and life partner Ewan MacColl (they didn’t actually marry until a decade before his death) had strong feelings.

Peggy Seeger, now 82, has spent most of her life in Britain, arriving in 1956 via the Netherlands, a Radcliffe dropout invited to London by Alan Lomax to play banjo in a group he’d hoped would be Britain’s answer to the Weavers. It didn’t work out but sitting in on the audition was MacColl, who offered Seeger a ticket for The Threepenny Opera, in which he was playing the street singer. He was 41 though claimed to be 38. That first night he drove home but didn’t touch her, merely told her he wanted to “make love” to her. Very soon he was doing just that, though he made no secret of the fact that he was already married, for the second time (his first was to Joan Littlewood, the celebrated theatre director). It was left to MacColl’s feisty Scottish mother to inform the pregnant Peggy that Ewan was also expecting a child by his wife. That child was Kirsty, whose life would be cut tragically short by a jet skier.

The names of Ewan McColl and Peggy Seeger would henceforth be joined by an ampersand on thousands of record sleeves and concert bills. The pace of their life together was relentless and tough, lacking in money until one day the mail brought a cheque for $75,000, thanks to Roberta Flack’s hit recording of the song that gives Seeger’s memoir its title. Flack’s was one of myriad versions, most of which were met with laughter and/or derision by MacColl, who wrote the song for his new love to sing when she was in residence at Chicago’s famed Gate of Horn in 1957, before tours of the Soviet Union and China resulted in the loss of her American passport. Think about it: a love song for his new love to sing to him, the writer. Beautiful as the song is, such vanity does not sit well with the supposedly humble, sharing, folk tradition. MacColl was macho through and through, allowing Peggy to endure four abortions from which he mostly absented himself, eventually agreeing to the snip with only the greatest reluctance.

But love against the odds is the stuff of folk song and there’s no denying the importance of MacColl and Seeger’s creative life (to which family life was always subservient), crisscrossing the country collecting songs from navvies, fisherman, gypsies and many other communities. The zenith of their achievement was The Radio Ballads, the eight landmark audio documentaries created between 1958 and 1964 with BBC radio producer Charles Parker, who tried to take most of the credit and who - unlike his collaborators - was squeamish about breaking bread with working people who he’d brought up to believe were not so clean.

But love against the odds is the stuff of folk song and there’s no denying the importance of MacColl and Seeger’s creative life (to which family life was always subservient), crisscrossing the country collecting songs from navvies, fisherman, gypsies and many other communities. The zenith of their achievement was The Radio Ballads, the eight landmark audio documentaries created between 1958 and 1964 with BBC radio producer Charles Parker, who tried to take most of the credit and who - unlike his collaborators - was squeamish about breaking bread with working people who he’d brought up to believe were not so clean.

For decades they presided over various folk clubs, regular gatherings in pubs across London where amateurs - so-called floor singers - could do a spot. Skiffle, which bridged folk and rock, brought many three-chord wonders into such clubs and Peggy laughed a cockney lad’s version of “Rock Island Line” out of court. That was, she later acknowledged, “most unprofessional”. The incident led to discussion as to what was appropriate and the Ballads and Blues Club laid down guidelines, renamed itself the Singers Club - and in due course gave a callow Bob Dylan a hard time. MacColl famously dubbed him “a youth of mediocre talent” though the notorious incident is not recounted by his widow.

Seeger has written celebrated songs of her own, among them “I’m Gonna be An Engineer” and “Carry Greenham Home”, both now anthems of the women’s movement which Peggy eventually embraced. Glasnost enabled her to return to the US, where she toured and taught, establishing (not without difficulty) a solo career following MacColl’s death in 1989.

Separately and together, Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger were, and are, remarkable and their contribution to Britain’s musical and wider cultural life cannot be gainsaid. Throughout it all, they were true to themselves and Seeger’s memoir is a remarkable account of a remarkable life.

In 1979, a low point for folk music, I was a student in Liverpool and brought them to the University for a concert, which was well attended. I had a budget to take them out to dinner afterwards. Absolutely not, they responded, bringing out a flask and a basket of sandwiches. We repaired to my room, where we shared them, along with my mother’s home-made fruitcake. It was a memorable evening.

- First Time Ever: A Memoir by Peggy Seeger (Faber & Faber, £20)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment