CD Special: Bob Dylan's Trouble No More review - he’d never sound better | reviews, news & interviews

CD Special: Bob Dylan's Trouble No More review - he’d never sound better

CD Special: Bob Dylan's Trouble No More review - he’d never sound better

Revelations: the gospel years get the Bootleg Series treatment

After more than 35 years of subterranean bootleg life, Bob Dylan’s incendiary gospel shows and sessions from 1979 to 1981 are seeing the light of day as volume 13 of the Official Bootleg Series.

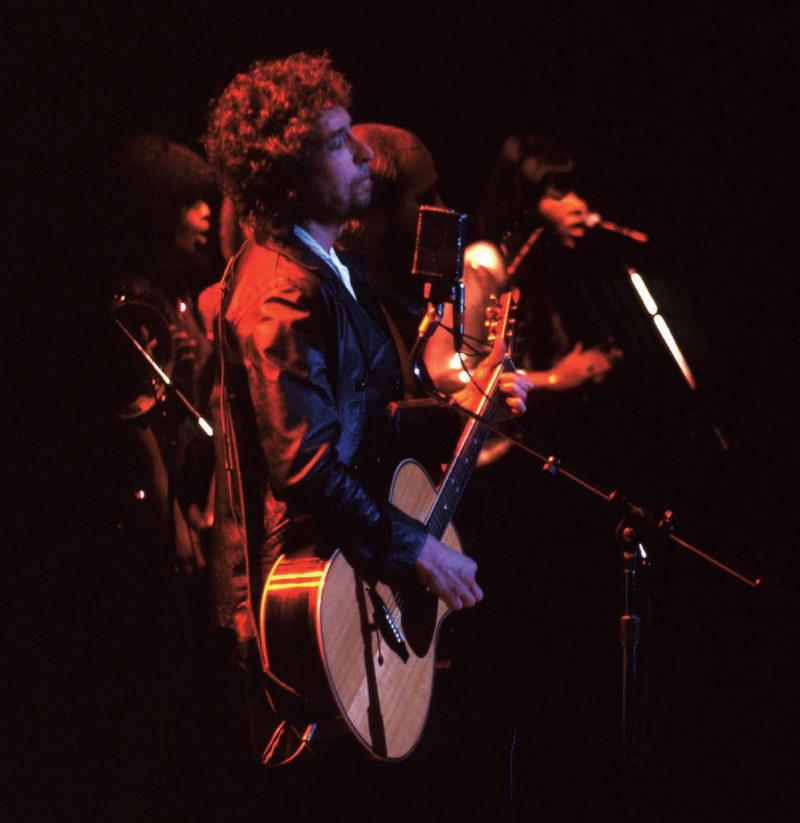

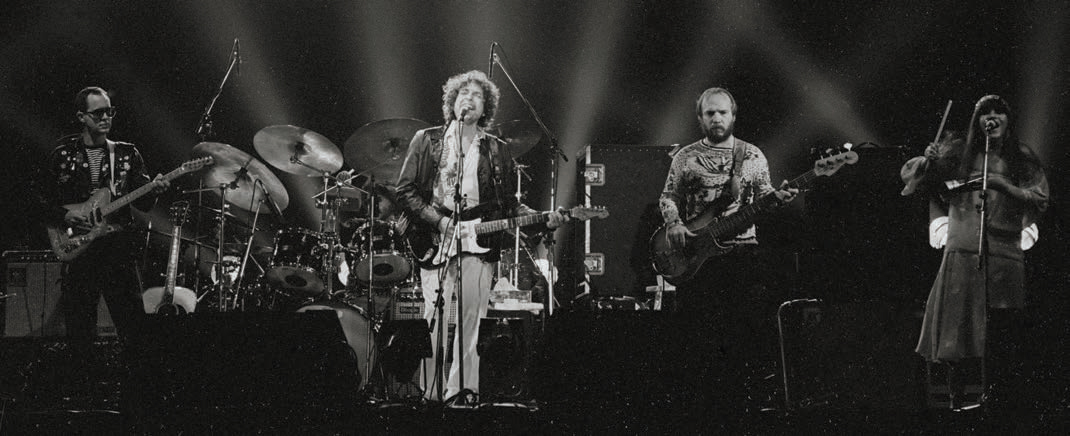

“It was exciting because it was controversial,” says Little Feat guitarist Fred Tackett of those extraordinary three years. He first got the call shortly after Lowell George’s death, and would feature on the 1979-1981 tours as well as the albums Saved and Shot of Love. “I’d come off the road, and they wanted me to come down and jam with them. So for three weeks I’d drive down to Rundown Studios in the middle of Santa Monica, a funky little place upstairs, and I started jamming with Tim Drummond, Jim Keltner, Spooner Oldham and Terry Young – who was an amazing gospel piano player – and Mona Lisa Young [her voice graces BA’s famous “Flower Duet” commercial] as well as the gospel singers. We played all the songs from Slow Train Coming and the new songs from Saved, then we went on the road, playing all these songs that hadn’t even been recorded yet.

“Slow Train Coming” features on six of the eight CDs on the deluxe set, ranging from a sparsely-worded soundcheck from the 1978 tour through the full-on might of the gospel concerts of 1979 and 1980 to the European retrospective tour of 1981, when Dylan eased his foot from the pedal of revelation and admitted his secular songs back into the repertoire. “I really enjoyed it when we played the old songs,” says Tackett of the 1981 tour. “The concerts by then were like a really good Dylan concert.” But the electrifying atmosphere of the 1979 performances at the Warfield Theatre in San Francisco, when Dylan launched his gospel crusade with a two-week residency, is hard to match.

“When we first went out and were playing only the gospel songs, it was definitely passionate and dangerous,” remembers Tackett. “Bob was on a mission. We felt like our job was to fulfil the musical vision that he wanted to put out. We tried to make it as good as possible so that people couldn’t deny it.”

Bob was on a mission. We felt like our job was to fulfil the musical vision that he wanted to put out

Deny it many people did, starting with the critics at the first Warfield shows. “That was a whole drama,” says Tackett. “We had Madalyn Murray O'Hair, a famous atheist, protesting. There was a guy walking up and down outside with a giant cross. It was a whole theatre going down on the street. And the reviews were terrible! There was a guy making good money busking old Bob Dylan songs, because you couldn’t hear them inside. The best thing I saw was a guy in the front row with a sign that said, ‘Jesus loves your old songs’, which I thought was a good point.”

Tackett’s fluid, funky rhythm and lead guitar features all across this set, propelling gospel rockers like “Solid Rock”, “Gotta Serve Somebody” and “Change My Way of Thinking” from their album versions into revelatory live performances of commitment and fervour. Discs one and two are concert recordings from 1979-1981, and comprise the stand-alone two-CD set, but there is good reason to stump up for the deluxe model. First, it includes Jennifer LeBeau’s Trouble In Mind, an hour-long documentary drawn from footage shot in Toronto and Buffalo in the spring of 1980 (discs five and six are also drawn from these Toronto dates), interspersed with "sermons", whose themes were apparently suggested by Dylan to Luc Sante, and are delivered by actor Michael Shannon.

“I was amazed, man, it was so good,” says Tackett of the film. “They picked the very best songs for it. Him and Spooner Oldham playing this harmonica and Hammond organ together at the end of “What Can I do for You?”. Spooner would play these chord substitutions under Bob’s harmonica, and it was just so cool and hip, and Bob is playing so great. They found the best stuff of all that and put it in this movie.”

Out of the 102 tracks on the deluxe set, there is only one previously released performance, and more than a dozen previously unheard songs from stage and studio. Discs three and four – “rare and unreleased” – contain the studio gems, rehearsals, alternate takes and incandescent stage performances that never made any record. They are outstanding examples of the singer at his pure, uncorrupted and utterly committed best. Even the simplest praise songs, such as “Blessed Is The Name”, propelled by Hawkwind’s “Silver Machine" riff, manage to rock the rafters.

Card-carrying Boomer liberals largely hated the transformation, identifying it with a politically conservative Born Again movement, but there is a wide beam of light that separates the raging group orthodoxies of politicised fundamentalism, especially as we know it now, and the personal, experiential and metaphysical evangelicism of Dylan. It was singularly his to own. He was a preacher preaching to an audience, for sure, but he was talking to himself, too.

The music is by turns supple, funky, full-on, full of fire and heat

Of course, he needed a great band behind him, and in Fred Tackett, drummer Jim Keltner, Muscle Shoals’s Spooner Oldham and Terry Young on keys, and the “wall of Jericho” that was Tim Drummond’s bass, he had one of the best. Then there were the gospel singers, ranged on Dylan’s right-hand side, filling the halls with rapturous harmonies, and the man himself, not so much in possession of all his faculties as possessed, entirely, by an evangelical spirit and a mission to manifest that spirit in concert conditions. He’d never sound better. Whether you can stomach the sacred over the secular is another matter, but if you can do it with JS Bach or Mahalia Jackson, why not with Dylan?

As a set, Trouble No More is up there with Another Self Portrait as a revelatory exposure of a period on which the lights have gone down, if not out, and rivals 1966 for the power of his concerts – just check out the final two discs from Earl's Court. The notes and essays are detailed and informative, but it’s worth picking up Clinton Heylin’s Trouble in Mind book from Route Publishing as a companion read. It includes a full sessionography and concert details, and tells the whole gospel saga in a straightforward, chronological order, with good source interviews and archival research, delving into the press reactions of the time to give us a vivid account of what Dylan was going through – and what he challenged his audiences with.

However austere the message sometimes is – Nick Cave once described Slow Train Coming as “a great record, full of mean-spirited spirituality… a genuinely nasty record, certainly the nastiest Christian album I've ever come across” – the music is by turns supple, funky, full-on, full of fire and heat, and raging like a torrent. Take the last eight live tracks of disc two, from “Pressing On” through superb versions of “In the Summertime”, “Groom Still Waiting at the Altar”, “Caribbean Wind” and “Every Grain of Sand”. Aside from “Pressing On” (one of Tackett’s favourites, describing it as “one of the funkiest things we ever did”), each one surpasses the album versions by some distance.

There is one major, previously unknown recording here, “Liar Out of Me”, which Dylan ran through just three times, and performed in its entirety once, sounding closer to first draft than polished artefact, and all the more fascinating for it. The liar was perhaps within, rather than some third party, as if Dylan is addressing the doubting self that figures in several of the later songs of this period. For most of us, after all, doubt is easier to deal with than faith. Lyrically, you can tell it is still in the making, raw material ready to be shaped, smoothed and shipped, a half-cut stone emerging from the bedrock, like the slave’s knee rising from raw stone in those unfinished sculptures by Michelangelo displayed in the same room as his statue of David in Florence.

There is one major, previously unknown recording here, “Liar Out of Me”, which Dylan ran through just three times, and performed in its entirety once, sounding closer to first draft than polished artefact, and all the more fascinating for it. The liar was perhaps within, rather than some third party, as if Dylan is addressing the doubting self that figures in several of the later songs of this period. For most of us, after all, doubt is easier to deal with than faith. Lyrically, you can tell it is still in the making, raw material ready to be shaped, smoothed and shipped, a half-cut stone emerging from the bedrock, like the slave’s knee rising from raw stone in those unfinished sculptures by Michelangelo displayed in the same room as his statue of David in Florence.

Which brings us to how we measure devotional art in a secular culture. Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel may be a long measure of distance from Dylan’s Rundown Studios in that funky upstairs room in the middle of Santa Monica, where a lot of these two- and eight-track recordings came from, but it was the room in which the sinew, muscle and spirit of Gospel Bob was created, amplified and sent out in to the world, a dramatising figure of and from an acutely Dylanesque amalgam of traditions, transforming itself into a challenging and energising force. You can take it to heart or take it on the chin, but this music is for the ages, and it’s time is coming round again. Are you ready?

Watch Dylan rehearse Every Grain of Sand at Rundown studios

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Yazmin Lacey confirms her place in a vital soul movement with 'Teal Dreams'

Intimacy and rich poetry on UK soul star's second LP

Yazmin Lacey confirms her place in a vital soul movement with 'Teal Dreams'

Intimacy and rich poetry on UK soul star's second LP

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Add comment