theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Olari Elts in Tallinn | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Olari Elts in Tallinn

theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Olari Elts in Tallinn

From contemporary ensemble to top orchestra, the latest major Estonian has arrived

Arriving in Tallinn hotfoot from Paavo Järvi's inaugural concert as chief conductor of Zurich's Tonhalle Orchestra, and expecting the limelight to belong to composer Erkki-Sven Tüür on his 60th birthday, I found another Estonian bonus in store.

News couldn't be broken until December, but in the light of an inspiring concert, I eagerly took up the orchestra's offer to interview Elts in a cafe just up the road from the concert hall, around the corner from his Tallinn home and opposite the flat where a former teacher used to hold discussions with regular visitor Shostakovich (more of that in the interview). So here we are with the good news finally public, and transcribing our chat held over the loud Saturday morning buzz in the cafe, I realise how much a part of the big change in Estonian musical and national life Elts, born in 1971, actually represents.

DAVID NICE Those are big shoes to step into. Did you grow up with Neeme Järvi as the national example of great conducting?

OLARI ELTS He emigrated to America in 1980, I was nine at the time, and then he returned with his Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra nine years later. I remember those concerts so well - they played Nielsen's Fifth, Sibelius Second, but I was especially amazed by the timpanist in Arvo Pärt's Third Symphony. It's fascinating where that piece sits in his output, in the middle of the desert years, 1971. I will admit that before I heard the performance I had a problem with Pärt's music, I liked the earlier, more avant-garde, music, but coming to the later works took time. For me the key was the Third Symphony, the concert was very important for me. The Sibelius was amazing. That was one of the first times when you could hear a foreign orchestra from western Europe playing here in this hall [the Estonia Concert Hall, inaugurated in 1913]. (Pictured below: Elts conducting the ERSO in the Tüür concert).  Was contemporary music your first love when you were training?

Was contemporary music your first love when you were training?

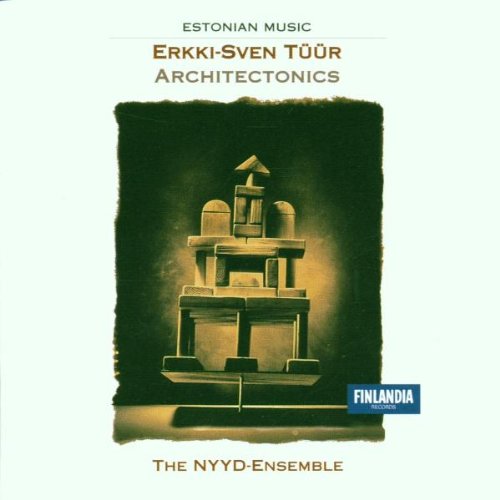

Like all orchestral conductors in Soviet time I started with choral conducting, because then that was the only option. In Estonia at that time we had no orchestral conducting department at all, most conductors including Neeme did their first diploma as a choral conductor and then they went to Leningrad, or one or two to Moscow. I studied choral conducting in our Conservatory [now the Music Academy], and then the wall came down, so I thought I'd go in a different direction, so I did a couple of years in Vienna in the 1990s, with Uros Lajovic, alongside Kirill Petrenko. I also studied here in Estonia with Paul Mägi, Eri Klas and Roman Matsov, and in Finland too, with private study and masterclasses with Jorma Panula, I owe everything to him, he was my most important teacher, Jorma, and as probably for most conductors in the north, last 20 years, so that's the background. Then during my student years, we had a new music festival here called NYDD which we did together with Erkki-Sven and a fabulous producer, Madis Kolk. There was also a desperate need also to have a new music ensemble of the same name, so we started one together with friends and it turned out to be the perfect laboratory to learn in. I was a field where no-one could follow me, because new music was a black hole. We began from the very beginning of the 20th century new music ensemble repertoire, because during the Soviet time to play western new music was not really recommended.

It seems that with the Khrushchev thaw, which is way before your time, dodecaphony could be discussed, but then it reverted again.

We did discuss it, luckily we had a teacher who brought back western LPs from his trips abroad, so we were listening, so we were listening to a lot of 20th century music kind of half secretly and analysing it, but on the concert scene it was a little tricky to get it performed. So we had to catch up quickly, starting with more classical stuff like [Stravinsky’s] L’histoire du soldat and the new Viennese school, we filled those gaps as quickly as we could until we came to Boulez, Berio, Birtwistle and all those guys. And the other goal was to change the new music scene here in Estonia, because the whole attitude was very oriented to eastern European during the Soviet time, when the authorities were not willing to let us play even the new Estonian music, so we managed to change that mentality. And we did give opportunities to Estonian composers, in a lab-like environment, because working with a flexible ensemble you could be much more adventurous. We also tried to commission from outside, which in the 1990s was not easy.

Whom did you commission?

It meant mainly doing it with festivals or co-commissioning. We started with some young composers but also included some names not very well known here at the time, say Jay Schwartz and even Gavin Bryars, alongside Estonian composers like Helena Tulve [now co-director of Estonian New Music Days, the major spring festival in Tallinn] , Lepo Sumera, Toivo Tulev, Galina Grigorjeva and Jüri Reinvere.

So you came to maturity with Erkki-Sven, though you’re younger…

Ten years younger. He was already quite a big figure in the 1990s. First concert we played Erkki-Sven’s Architectonics 6.

At this year's Europe Day Concert in London, where the theme was '25 and Under: Young European Composers,' we went back to Architectonics 1 for wind quintet, and the audience loved it.

It’s a great piece – and No. 3, sadly it’s rarely played, the Post-Metaminimal Dream,because of two pianos in the ensemble, No. 6 is our favourite - we've played it more than 20 times. We’ve played them all, recorded them. And then he wrote some pieces for us, the Marimba Concerto with Pedro Carvelho, this amazing percussionist from Portugal, who’s also a conductor of the youth orchestra there, they do amazing things. So that’s the background – it’s new music for many reasons, because it was the work which had to be done. We stopped when we saw that the scene has changed, and the logistics were difficult, and the key players had positions in different orchestras in other European countries.

It’s a great piece – and No. 3, sadly it’s rarely played, the Post-Metaminimal Dream,because of two pianos in the ensemble, No. 6 is our favourite - we've played it more than 20 times. We’ve played them all, recorded them. And then he wrote some pieces for us, the Marimba Concerto with Pedro Carvelho, this amazing percussionist from Portugal, who’s also a conductor of the youth orchestra there, they do amazing things. So that’s the background – it’s new music for many reasons, because it was the work which had to be done. We stopped when we saw that the scene has changed, and the logistics were difficult, and the key players had positions in different orchestras in other European countries.

So the ensemble doesn’t exist any more?

Strictly, no. Now we have many new ensembles in Tallinn, the new music scene is healthy and blossoming.

The Estonian New Music Days in the spring is so impressive – this year was international, but the fact that you could have five days of music by Estonian composers, many of whom I’d not heard – this is amazing for a small country.

Yes – it has a long tradition from Soviet times, because the Composers’ Society was a powerful organisation, and the position of the composer or an artist then was very different. The same was true of theatre - people used to have to read between the lines, just as they tried to find hidden messages in concerts.

I remember when I came with the Gothenburg Orchestra in 1989, David Pownall’s play Master Class was being performed, about Stalin, Prokofiev and Shostakovich.

I remember that – it was amazingly well acted.

Choral festivals were very important then, weren't they, and still are.

I went to the Latvian one for the first time last year. It was a shame it was amplified, because that way a choir of 15,000 sounds like a choir of 100. What interested me was that you had the old standards, very elaborate and beautiful, and now it sounds to me like it’s disintegrated into Euro-pop, so there’s less in the way of serious stuff being written.

I do not see that danger yet too threatening, even though in the song festival for youth, which happens also every fourthh year, there’s much more music with band or orchestra. However in our main festival I see that the a cappella tradition is still strong and present. I feel that should be the rule also for the young people’s event, that we always have at least one or two a cappella songs for every age group. Even for the youngest kindergarten choirs. They are by the way absolutely phenomenal.

The concert last night – I think everyone agreed that the recent works of Erkki-Sven’s made almost a trilogy. Who chose the programme?

Erkki-Sven. I thought, this is the moment when you have to let him do it, and I said, I’ll conduct whatever you decide.

I felt it worked amazingly well because each had its own life, but they shared some of the same hallmarks.

They do indeed, very different pieces but with slightly similar structure - a slow introduction that very organically develops until you reach ever bigger climaxes and then the sudden return of the slower section with a lot of afterglow..

Those slow codas are spellbinding.

Yes. Also the way he uses the flutes, with harmonics and overtones - you keep the same fingering and you go up and down with the natural scale. When Erkki-Sven uses alternative playing methods or notation, it always serves a certain idea, it’s never just for effect. There’s always this deeper meaning – even when he writes a concerto, it’s basically a symphony, it’s instrumental in the symphonic sense. In a way he’s an old-fashioned symphonist, in the best sense of the term, in the way he builds huge structures from tiny material. And the way he limits and organises himself harmonically in his own vectorial writing system has substantially changed his soundworld to create a completely unique musical landscape. It has been fascinating to see how that initially rathery dogmatic system has grown in him and givene him very different kind of freedom. In the Fifth Symphony you can see the more mathematical side of this system, while in the Eighth and Ninth and in recent concertos, it’s at a completely different level. [PIctured below, Elts and Tüür with members of the ERSO after the performances].

What I love is that it starts with what one could call process and then you get these amazing figures and hooks, so that it evolves from natural into human matter, I don’t know if you see it that way.

What I love is that it starts with what one could call process and then you get these amazing figures and hooks, so that it evolves from natural into human matter, I don’t know if you see it that way.

Definitely. What you call the “human matter” is coming back more and more. And I think that the Ninth Symphony has more late romantic gestures than any of the other symphonies.It has the “human matter” in the way we see in Mahler symphony in a deeply human, philosophical sense. it also incorporates the strongly rhythmical side of his earlier work which needs utterly precise interpretation. It has this spot-on the beat playing with the drum-set, which is necessary because when it gets rhythmically really difficult and you do not really play on the beat, then the vertical doesn’t work; it’s chaos. This is the part you have to practise the most.

That was so impressive – he said so too.

And this is the orchestra which knows, because it has had a very long relationship with Erkki-Sven's music. Interestingly enough, we discussed this with a couple of players a few days ago, how actually this is the way of having contemporary music of this kind which actually helps when going back to late 18th century repertoire is helpful to play the classical repertoire, because it is very disciplin-ing. Because we don’t talk about stylistics, the style of something. Here the orchestra gets that there is something behind the notes, in the same way as they play a Mahler symphony or the German repertoire. Erkki-Sven has ;ong been able to combine very different elements including this sense of a very delicate late romantic idiom. It was stronger in his 1990s music where you have those long lines and this very distinctive “crystallisation”- He explains it himself in one of his early pieces with the same name - “that it’s the moment where the water starts to freeze”. In this “crystallisation” there is a whiff of distant nostalgia. This is where we get the connection to Sibelius..

Also having heard two symphonies by Lepo Sumera [1950-2000] in the spring festival, these are big post-Mahlerian statements.

Indeed! In Sumera, that romanticsm is combined even smore srongly tronger with Eastern European or I would even call it Estonian minimal music that is on the way to “new simplicity”. Call it “Estrhythmus”; it has that has some roots in our older folksong “Regilaul , our equivalent to Finnish “Runo”. This Estonian minimalism was in the 1960s somewhat mixed with the neoclassical and energetic, “Zeitgeist” way of writing - especially so in the case of composer Jaan Rääts who was also Erkki-Sven’s teacher. In the 1970s and 80s Raimo Kangro took it to another level, by adding a lot of irony. It's Interesting how all these indications of minimalism were in the air - how it was so completely different from what happened in the States in that field, simultaneously. The Zeitgeist was present even if the borders were totally closed and information did not really travel. The first indications we could see in both the west and east already in 1920s in the music born from the industrial revolution. .

The 20s was an incredible time in Russia, wasn’t it?

It is one of the most interesting periods in Russian music. In fact, I would say it is bar none, the most avant-garde period with composers like Roslavets, Mosolov, Shcherbachov, Popov, Avraamov and others.

And Berg was still being performed there – Wozzeck had its Soviet premiere in 1927.

Interestingly enough. Le sacre (The Rite of Spring) wasn't even performed there until 1965! In a way the fact that this piece arrived so late has influenced the entire 20th century music in eastern Europe. So, what you just said about Berg is almost unconceivable, but on the other hand it can be indeed interpreted in a rather “Soviet-friendly” way. That expressionistic score with all those rhythms must have been great challenge to face at that time. Erkki-Sven’s rhythmical structures started rather conservatively compared to his currently sometimes rather compex patterns, so he was one of the first composers who did not fit to the usual 1990s “Eastern Europeanness” box.

You’re friends?

We’ve become friends, yes. It’s interesting. As a conductor you can’t really influence a composer, despite aspects like commissioning the piece, that’s it.. And I like it that way, because as we know, most of us, the interpreters, can more or less influence only the present - composers create the future. I cant remember who said "we do not feel the smell of the 'new path' as composers do".

The way you conduct may influence the way he writes in future. He may hear things that you bring out…Last night was incredibly clear but also emotionally involving all the way through. It was a full house, but a discerning audience. In the UK it’s very difficult to sell out a concert of contemporary music.

Well, it’s the same here. Except if it’s an Arvo Pärt or Erkki-Sven concert, especially if it’s an anniversary concert. Normally we’d count the audience for contemporary music in a couple of hundreds.

More so han before. I think it makes sense to combine.

You want to develop that?

Definitely – and it’s not just because I love it, it’s also my duty. What I’ve learnt from my son, which was surprising to me, but now it seems so organic, is that the younger generation relates much more easily to contemporary music, which is always surprising. Roman is 10, he sent me a text after the concert last night – he liked everything. When he was five or six he heard a mixed programme with 12 celli and a piece by Xenakis was the one he liked most. Younger ears have a slightly harder time relating to Mozart than to contemporary music..

It’s easier because there is a freer world, there's much more variety now. You can have five or six works in a programme and they can all sound completely different from each other.

I think we've been experiencing this freedom and variety since the beginning of the current century’s happy Post-Intercontemporain, or post-Darmstadt era. Of course both of those are still strong institutions and I admire them both. You know the French composer-organist Thierry Escaich - I want to bring him here, we’ve done a few things together – I remember when I was reading the booklet for his first CD, he spent most of the time apologising why he wrote this kind of music. I can only imagine how difficult it would have been at that time. The way we develop programmes now is very different compared to the end of 20th century. We have more freedom to combine and create new and unusual connections. On the other hand, there's also more freedom in how an orchestra plays the classical repertoire. We know how far it went from the “urtext” during the last century. And then we had that so desperately needed HIP. There’s an interesting book about this written 15 years ago called The End of Early Music by Bruce Haynes, a man who does not necessarily like conductors. With all the lessons of the past now behind us, and the de-fetishizing of the conductor’s profession, it's really cleared the air.

It’s a greater era of collaboration, there are fewer dictatorial conductors.

There’s a feeling of more participation when it comes to organising the work, conceiving ideas and inspiring the orchestra. Of course we have all those great figures we deeply admire, but you take the score and see what it is written, then you listen to the conductors of the 1960s...

Even when you listen to some of Neeme’s old-style Mozart…

But he’s done very good Haydn, and the recordings he did with the Estonian orchestra in the 1970s are very fine, very interesting. Neeme has done a terrific job.

When I was a student in Edinburgh in the 1980s, I went to all his concerts with the Scottish National Orchestra, and those were definitely amazing mixes of classical and contemporary. I'll never forget the impact of Arvo Pärt's Credo for chorus and orchestra.

That’s an amazing piece..It has this collage taken to a schizophrenic level, to an inner duality.

It's a great argument for C major in the form of the Bach Prelude, isn't it?

It always has this overwhelming effect. It's important to remember that when Pärt got to this point he still had to hide the message. Already the title of the piece was on the edge, or actually further than the edge. Together with Perpetuum Mobile and Nekrolog, also collages in the Prague Spring/Warsaw Autumn style if you go back in Estonian music history, Arvo Part is unquestionably most avant-garde Estonian composer!

As for your relationship with the orchestra – you know the players well?

It’s a homecoming for me, on many levels. This was the first orchestra in my life, and it was the first orchestra I ever conducted. This puts me in a unique position. Many of the same players that are still with this orchestra were once classmates who I used to study with. This is also the orchestra that I knew best while listening to classical music concerts in my childhood, and the one that I took my conducting exams with. It's a part of my very foundation. The chance to build that history and arrive at the next level together is full of both challenge and possibility. .

There’s also a new generation.

Maybe half the orchestra is younger than me. Triin [Ruubel-Lilleberg, the leader, pictured below with Elts at the Tuur concert] is exactly as old as my stepdaughter. It's an illuminating moment when you see a lot of people who are younger than you.

It’s lovely to see the continuity, the rising standards.

Exactly. Especially in a philharmonic symphony orchestra where the importance of different generations playing together is so essential. And it’s become more equal now, between the groups. There was a time in the 1990s when a lot of orchestral members left, but now we are on the right track, I think, and it’s definitely going uphill at the moment. For the orchestra, the psychology is good, the working atmosphere is good. [We discuss the nature of the Tüür pieces, and he refers to the Beethoven fragments in the first piece, Phantasma, as "like seeing a face at the bottom of the water, no more than that". I refer back to Prokofiev and how he talks about the works of the 1930s as allowing you occasionally to glimpse "the outlines of a real face"]

[We discuss the nature of the Tüür pieces, and he refers to the Beethoven fragments in the first piece, Phantasma, as "like seeing a face at the bottom of the water, no more than that". I refer back to Prokofiev and how he talks about the works of the 1930s as allowing you occasionally to glimpse "the outlines of a real face"]

I like most what he wrote in the 1930s. The symphonies are a bit more mysterious for me. It's the way the ballet-music influence makes them light on the surface, but there are depths under that. I haven’t yet worked out how to do this for myself, I haven’t found the key. The Fifth I have done, otherwise Shostakovich is the one I’ve done more. I am from the last generation who still knows the difference, for whom freedom is not a cliché, and that sounds in itself like a cliché, but it has profound meaning, it really has. By the way, after the war, always the third performances of the new Shostakovitch symphonies were happening here – after Moscow and Leningrad, because Roman Matsov became the chief conductor before Neeme, in 1956, and he lived in this house [points opposite], you see those three windows? He had long conversations with Shostakovich about music and life here. Many of Roman Matsov’s scores are filled with Shostakovich comments, and those scores might be still here in this flat. He died in 2001, but his children are keeping the flat and sorting the scores is a work in progress.

What was the first Shostakovich you heard?

Probably the Seventh, but I’ve mainly done Six, Seven, Nine and Ten. Roman Matsov was not a guy who was known in the world at large, for obvious reasons, but he was really appreciated in the East, as a Beethoven specialist. He spoke in slightly peculiar Estonian. We didn’t really always understand what he was trying to say, but it was absolutely clear for me when I came back from Vienna how great this man is. Many generations of Estonian musicians including me studied with him. He was such a character, and he smoked like crazy; there were cigarettes and many ashtrays in every room in his house, and on both sides of the piano. He would forget he’d lit one up when he lit another. He had a kind of ongoing group who would come to his home, including all young conductors. It was kind of “fratres”. Yes, as far I know, Pärt had some connection to him too. Nothing started before 8pm, because he was working before that. And the last students came at 11 or something. I tried to be always the last one, because then we could have a longer discussion about life and music. It was always difficult, because it was almost impossible to swim through the smoke. But he had an extraordinary, pre-war way of seeing life and music, which was very different from the usual Soviet drama.

Now we realise that Shostakovich was not too exaggerated about the craziness of the system, and now we see how crazy it can be with Trump and the Far Right. I understand it better, though it can always be understood as music.

It has never been as contemporary as now, for Western Europe, and the western part of the world has never understood Shostakovich as well as it does now. It’s a bit similar to Mahler, who has become more and more contemporary. What I love about Shostakovich but also find challenging is to shape his slow movements, and discover the layers they reveal. On other hand his shortest symphony, the Ninth, is the most misunderstood.

It's not at all a light work.

He couldn't celebrate the end of the war in the way that Prokofiev did with that extraordinary Ode and its bizarre combination of instruments including eight harps and four pianos - we performed that here, incidentally. With Shostakovich Nine, it starts light, then immediately we have this pragmatic "I do whatever you say, master” trombone motive. And suddenly there comes the power of evil, anxiety and fear in the second movement. And the third movement which is slightly like the scherzo of the Tenth Symphony - no-one should ever play that in a children’s concert as is sometimes done. Then the post-climactic bassoon solo, like if you wake up in the middle of battlefield and all your friends have betrayed you or have been killed. Then there is how the finale builds up, with big machinery and this huge black cloud covering the whole horizon which starts to come closer and closer. It’s at least as well done as in the Seventh Symphony, which is longer, but it creates the same feeling. So yes, there's also a lot of the Russian 20th century symphonic repertoire I want to include in the coming seasons.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

Add comment