First Person: Geoffrey Paterson on conducting the London Sinfonietta and working with Marius Neset | reviews, news & interviews

First Person: Geoffrey Paterson on conducting the London Sinfonietta and working with Marius Neset

First Person: Geoffrey Paterson on conducting the London Sinfonietta and working with Marius Neset

The conductor's 51st concert with a legendary ensemble due at the Proms tomorrow

By my count, tomorrow’s Proms première of Marius Neset’s jazz epic Geyser will be my 51st performance conducting the London Sinfonietta.

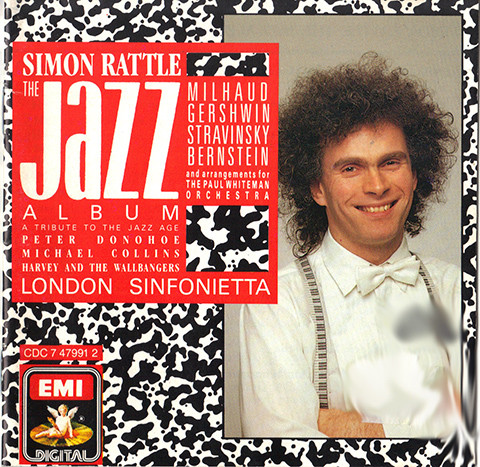

At that time it felt like a group with an almost mythic status, a name on the cover of Simon Rattle’s Jazz Album I had grown up listening to, and also frequently printed after the words “commissioned by…” on the title pages of the contemporary-music scores I had avidly started to collect.

The Jazz Album was released in 1987, and featured the London Sinfonietta alongside soloists including Peter Donohoe and Michael Collins. I listened to this wonderful CD hundreds of time as a child, but of course we have long since been aware that it is not a real jazz album! Its subtitle, “A Tribute to the Jazz Age’, as well as its list of composers (Gershwin, Bernstein, Stravinsky, Milhaud), gives that away, however thrillingly free and extemporised the final part of Prelude, Fugue and Riffs may sound.

The Jazz Album was released in 1987, and featured the London Sinfonietta alongside soloists including Peter Donohoe and Michael Collins. I listened to this wonderful CD hundreds of time as a child, but of course we have long since been aware that it is not a real jazz album! Its subtitle, “A Tribute to the Jazz Age’, as well as its list of composers (Gershwin, Bernstein, Stravinsky, Milhaud), gives that away, however thrillingly free and extemporised the final part of Prelude, Fugue and Riffs may sound.

In recent years, sparked by a request from the extraordinary saxophonist and composer Marius Neset to record an album of music he had written for his quartet and chamber orchestra, the Sinfonietta has taken several steps further towards the holy grail of genuine jazz-classical symbiosis. I jumped at the invitation to conduct this project and to collaborate with Marius on final tweaks to his score, and working with him has become an ongoing partnership I’m extremely proud to be part of. Some of the most inspiring experiences of my career have been alongside composers preparing premières of their work, with none more horizon-broadening than this first foray into the jazz world.

This album Snowmelt achieved something spectacular, Marius finding in his barn-storming music an ingenious solution to the pitfalls inherent in the integration of jazz musicians, who improvise different music each time they play, and classical players, who faithfully read the notated music placed in front of them. I was so happy that we never felt like a backing band, and certainly the fearsome difficulty of Marius’ writing justified the involvement of an ensemble so renowned for its virtuosity. Our follow-up album Viaduct took this even further, with little perceptible sense of division between the two genres, a merging that demanded a greater symphonic breadth as much as it did a tightening of the Sinfonietta’s jazz reflexes.

This album Snowmelt achieved something spectacular, Marius finding in his barn-storming music an ingenious solution to the pitfalls inherent in the integration of jazz musicians, who improvise different music each time they play, and classical players, who faithfully read the notated music placed in front of them. I was so happy that we never felt like a backing band, and certainly the fearsome difficulty of Marius’ writing justified the involvement of an ensemble so renowned for its virtuosity. Our follow-up album Viaduct took this even further, with little perceptible sense of division between the two genres, a merging that demanded a greater symphonic breadth as much as it did a tightening of the Sinfonietta’s jazz reflexes.

I’ve been lucky to conduct a huge range of different projects with the Sinfonietta over the last ten years. It’s a relationship that has introduced me to composers I might otherwise never have encountered (a concert of Basque contemporary music in Bilbao comes to mind), as well as giving me the chance to immerse myself in the work of some of the great composers whose histories have been inextricably linked with this ensemble over the last half-century, chief amongst them the recently-departed and much-missed Harrison Birtwistle.

I’ve been involved in a number of projects in unusual venues and formats, most memorably a new work by Matt Rogers that I conducted in costume in the ticket hall of Kings Cross Underground Station. There have been operas by Pascal Dusapin and Tansy Davies, music by Samantha Fernando to accompany short-story readings at the Southwark Playhouse, Hans Abrahamsen’s enormously difficult Schnee as a jump-in on four days’ notice, and the unforgettable experience of conducting Steve Reich’s City Life televised from an empty Royal Albert Hall as part of the audience-less 2020 Proms (Paterson pictured below by Chris Christodoulou).  The London Sinfonietta occupies a very special place in the landscape of British music-making. This has much to do with its longevity, its extensive discography, and the huge number of works it has commissioned over the 50-plus years of its existence, many of which have already transcended the ‘contemporary-music’ label and are recognised as bona fide classics of the late 20th-century and early 21st-century repertoire. I also think it is because the Sinfonietta’s history allows it to offer a context for the very idea of repertoire in a field often defined overwhelmingly by the quest for novelty.

The London Sinfonietta occupies a very special place in the landscape of British music-making. This has much to do with its longevity, its extensive discography, and the huge number of works it has commissioned over the 50-plus years of its existence, many of which have already transcended the ‘contemporary-music’ label and are recognised as bona fide classics of the late 20th-century and early 21st-century repertoire. I also think it is because the Sinfonietta’s history allows it to offer a context for the very idea of repertoire in a field often defined overwhelmingly by the quest for novelty.

The Sinfonietta is not just about the brand-new, and its legacy can be seen in the creation of a musical literature, a body of work to be returned to again and again, that can be mentioned in the same breath as the undisputed masterpieces of this blurry-edged and centuries-old tradition we still call classical music. Many of its principal players, though hugely skilled in tackling the extreme technical challenges the Sinfonietta’s programming requires of them, also hold principal positions in London’s leading symphony orchestras, and bring with them the depth of experience and musical insight that a regular diet playing Beethoven, Brahms, Mahler and Stravinsky at the highest level all but guarantees.

As a result, the artistic philosophy and flexibility of the ensemble, its approach to the music it plays, is the same whether performing an experimental world première, a 1960s classic, a early-20th-century work (Warlock’s The Curlew a recent example), or indeed when exploring a genre that fuses the worlds of jazz and contemporary-classical, such as the relationship with Marius Neset that reaches its third instalment at the 2022 Proms.  My impressions so far from the incredibly exciting score of Geyser I now have in my hands is that Marius is developing his compositional attitude yet further. Since Viaduct, he has written a saxophone concerto for himself and the Bergen Philharmonic in his native Norway, as well as a large-scale orchestral piece for the same orchestra, proving with these works an astonishing ability to write his music without jazz rhythm section, and in the latter without a single jazz musician involved.

My impressions so far from the incredibly exciting score of Geyser I now have in my hands is that Marius is developing his compositional attitude yet further. Since Viaduct, he has written a saxophone concerto for himself and the Bergen Philharmonic in his native Norway, as well as a large-scale orchestral piece for the same orchestra, proving with these works an astonishing ability to write his music without jazz rhythm section, and in the latter without a single jazz musician involved.

They reveal even more clearly than in Snowmelt and Viaduct the deep influence Marius (pictured above) draws from some of the great composers of the 20th Century - Stravinsky, Messiaen, Ligeti, also looking back to Mahler - without losing any of the intensely individual musical personality that is already distinct in his early saxophone solo Old Poison (XL), a polyrhythmic primer worthy of Nancarrow.

Tomorrow, we will share this new work Geyser with the world, live at the BBC Proms and on BBC Radio 3. It’s a project that fits so well within the gloriously rich and varied repertoire that the London Sinfonietta has helped to build and nurture since its founding in 1968, and it’s a source of great pride yet again to have been given the trust and privilege to steer this collaboration between one of the world’s most gifted jazz musicians and Britain’s pre-eminent modern-music ensemble.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Hallé John Adams festival, Bridgewater Hall / RNCM, Manchester review - standing ovations for today's music

From 1980 to 2025 with the West Coast’s pied piper and his eager following

Hallé John Adams festival, Bridgewater Hall / RNCM, Manchester review - standing ovations for today's music

From 1980 to 2025 with the West Coast’s pied piper and his eager following

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James's Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James's Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Add comment