Modernist art movements are a lot like totalitarian regimes. They produce their declaratory manifestos, send forth their declamatory edicts, and, before you know it, a Year Zero mentality prevails: the past must be declared null and void. Seeking to overturn 1,000 years of Western civilisation with a universal aesthetic utopia of brightly coloured squares and boldly delineated lines, a confident Theo van Doesburg, founding member and chief theorist of the Dutch movement De Stijl, wrote, “What the Cross represented to the early Christians, the square represents to us all. The square will conquer the Cross.” Blimey - and there you were, thinking the Dutch were always so reasonable, too.

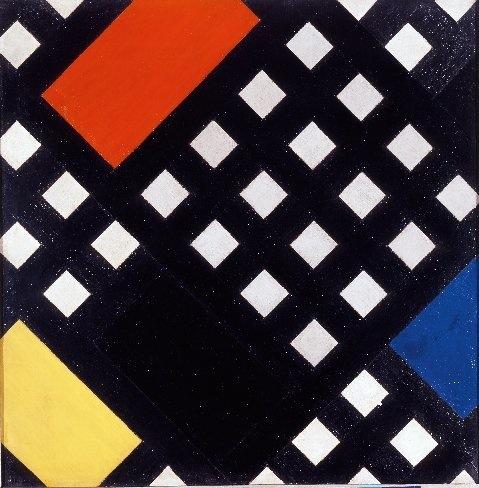

Take, for instance, the great quarrel over the diagonal. In 1923, van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian fell out over it. Mondrian held firm that the future lay in horizontal and vertical lines, while van Doesburg insisted that, no, the diagonal must be permitted (actually, one feels that van Doesburg may have been a bit of an anarchist at heart, and straight lines and squares simply couldn’t contain him, since he also flirted with the Dadaists under the pseudonym I K Bonset.) Needless to say, this led to a complete severing of relations, the two only resuming contact six years later.

Under the editorship of van Doesburg in 1917, De Stijl ("The Style") was founded initially as a journal, then as a fully fledged art movement. Painters, sculptors, designers and architects sought to unite their previously segregated art forms. So artists worked in practical design, designers in architectural practice, and painters in three dimensions. Designers including Gerrit Rietveld and architect J P Oud were soon inspired to join in. Moreover, it was a style that was to prove hugely influential to the Bauhaus, a movement that had previously adopted an English-inspired Arts and Crafts aesthetic. Still, you would never describe De Stijl as a homogenous movement: other artists whose aesthetic was quite removed from its strict geometry also featured, both in the journal and in the exhibitions van Doesburg organised.

Under the editorship of van Doesburg in 1917, De Stijl ("The Style") was founded initially as a journal, then as a fully fledged art movement. Painters, sculptors, designers and architects sought to unite their previously segregated art forms. So artists worked in practical design, designers in architectural practice, and painters in three dimensions. Designers including Gerrit Rietveld and architect J P Oud were soon inspired to join in. Moreover, it was a style that was to prove hugely influential to the Bauhaus, a movement that had previously adopted an English-inspired Arts and Crafts aesthetic. Still, you would never describe De Stijl as a homogenous movement: other artists whose aesthetic was quite removed from its strict geometry also featured, both in the journal and in the exhibitions van Doesburg organised.

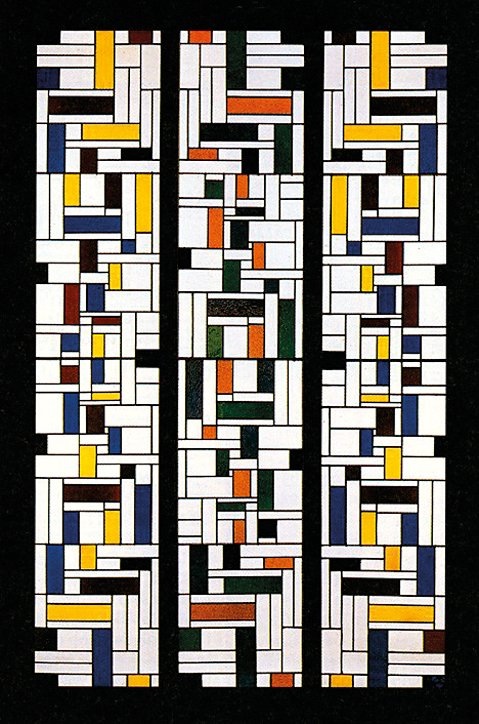

Tate Modern’s mammoth survey of the movement is really quite a marvel, beautifully installed, intelligently curated and rich with historical detail. Its sweep is broad and rigorous, rather like the movement it celebrates. It encompasses not only the austere geometric paintings - the Compositions, Decompositions, Counter-Compositions and Simultaneous Counter-Compositions - of Doesburg, but his architectural designs, his new typography, his poetry and his stained glass windows (the latter are quite lovely, in fact - pictured above). These are shown alongside the canvases of Mondrian, and one begins to appreciate how much more varied van Doesburg’s activities were.

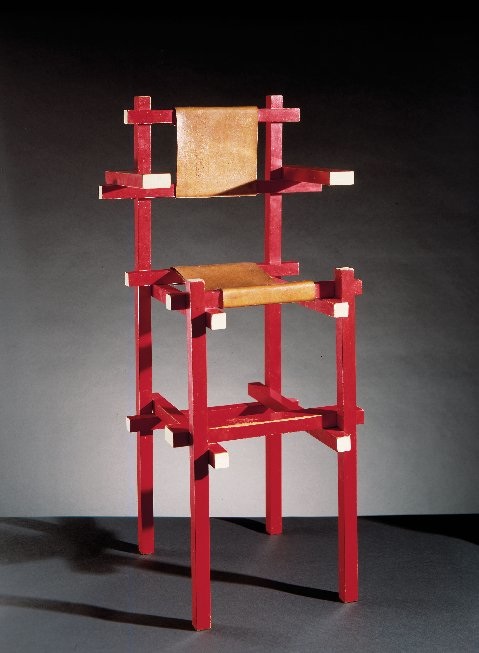

Although you may occasionally feel disengaged by the repetitious imaginary - you are certain to leave with retinas imprinted with primary-coloured squares - there are plenty of pieces that will simply stop you in your tracks. Rietveld’s furniture designs, for example. If you ever imagine modernist design to be, well, a bit on the bland side, then take a look at Rietveld’s beautifully crafted Sideboard (pictured right). With its jutting and intersecting lines, there’s a lot going on in that sideboard; it’s kind of like a beautiful, rather complicated symphony, a symphony in sycamore brown, perhaps. (It’s not for nothing that abstract artists have often given their works the titles of musical forms.) But then again, I’m sure you'd find no use for Rietveld’s Child’s Highchair. (pictured below). Comfort and safety were not, it seems, necessary requirements of modernist design

Although you may occasionally feel disengaged by the repetitious imaginary - you are certain to leave with retinas imprinted with primary-coloured squares - there are plenty of pieces that will simply stop you in your tracks. Rietveld’s furniture designs, for example. If you ever imagine modernist design to be, well, a bit on the bland side, then take a look at Rietveld’s beautifully crafted Sideboard (pictured right). With its jutting and intersecting lines, there’s a lot going on in that sideboard; it’s kind of like a beautiful, rather complicated symphony, a symphony in sycamore brown, perhaps. (It’s not for nothing that abstract artists have often given their works the titles of musical forms.) But then again, I’m sure you'd find no use for Rietveld’s Child’s Highchair. (pictured below). Comfort and safety were not, it seems, necessary requirements of modernist design

This labyrinthine exhibition reinstates van Doesburg to his rightful place. He was the driving force behind De Stijl, but unlike Mondrian he did not become a cult figure, nor even a remotely celebrated one. His name is largely forgotten. This is not because Mondrian was a better artist - I don't think he was, and excepting the direction of their lines, there is often little to distinguish their painterly styles. Rather, it is largely because Mondrian lived long enough to go off to New York just as that city was becoming the art centre of the universe. And, in turn, it was New York that inspired Mondrian’s wonderfully jazzy Boogie Woogie paintings. By then, van Doesburg had already been dead for nearly a decade, dying of a heart attack in his late 50s in 1931. And with him died the journal and movement he founded.

This labyrinthine exhibition reinstates van Doesburg to his rightful place. He was the driving force behind De Stijl, but unlike Mondrian he did not become a cult figure, nor even a remotely celebrated one. His name is largely forgotten. This is not because Mondrian was a better artist - I don't think he was, and excepting the direction of their lines, there is often little to distinguish their painterly styles. Rather, it is largely because Mondrian lived long enough to go off to New York just as that city was becoming the art centre of the universe. And, in turn, it was New York that inspired Mondrian’s wonderfully jazzy Boogie Woogie paintings. By then, van Doesburg had already been dead for nearly a decade, dying of a heart attack in his late 50s in 1931. And with him died the journal and movement he founded.

- Van Doesburg and the International Avant-Garde: Constructing a New World is at Tate Modern until 16 May

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment