Janáček’s opera subjects – the 300-year-old opera singer, the composer with a mad mother-in-law, the Siberian prison camp – are by any standards a fairly rum collection. But The Cunning Little Vixen is arguably the most deviant of the whole bunch. Its foxy heroine (out of a Prague newspaper cartoon strip) is captured by the local Forester, lectures his hens about their subservience to the Cockerel, slaughters the lot of them, runs off, marries, starts a family, then allows herself to be shot by the poacher. All very charming, random and pathetic, one might feel. But Janáček typically has other ideas, and the result, though not supremely operatic, is one of his most thought-provoking and touching stage works.

“Stage work” is a good, cautious description. As a vocal score Vixen is distinctly problematical. Uniquely for his operas, it has page after page of purely orchestral music, to which Nature dances, in the form of assorted forest creatures, dragonflies, mosquitoes, squirrels, frogs – a whole bestiary of buzzers, flutterers and nibblers. The fox tale itself is a very light brush. Through it thread the menopausal ruminations of a handful of ageing villagers: the schoolmaster, the priest, the poacher, and above all the forester, for whom the vixen he pursues is somehow a symbol of vanishing youth and potency. Life draws to a close, but Mother Nature recycles. In her end is her beginning; in our end is our end.

Sophie Bevan gives a vibrant, personable, acrobatic performance, with her lovely, easy production

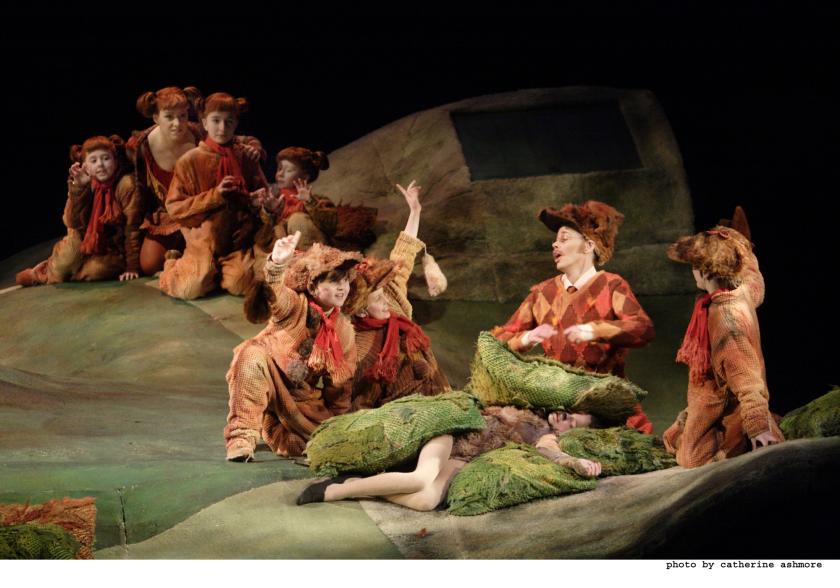

So Vixen plays on a number of levels. Nature is red in tooth and claw, sometimes, but the agony is also exquisite; and Janáček’s dance music captures this evanescent delicacy with an unblinking precision devoid of false sentiment, light in touch, occasionally dark in undercurrent. David Pountney’s production, now more than thirty years old, was always dazzling to the eye, thanks in large measure to the inventive wit of the late Maria Bjoernson’s anthropomorphic costume designs and the perilous brilliance of Stuart Hopps’s choreography, over what might be a slice of rough ground from a Welsh hillside. In Elaine Tyler-Hall’s revival, it all pops up as fresh as its forest setting.

For the singers, human or animal, life is not so carefree. Sophie Bevan, as the Vixen (pictured right), makes characteristic light of music that, even when sung in Czech, makes the words dance more than it lets them sing, and that here, in Pountney’s new English translation, often seems to lie awkwardly on the voice. She gives, all the same, a vibrant, personable, acrobatic performance, with her lovely, easy production, and surprising agility about the stage. She reminds us, too, of her fine command of a brand of ecstatic lyricism, in her love scene with the Fox – a nice, stylish performance by Sarah Castle which doesn’t, nevertheless, quite convince me that Janáček was right to make him a soprano (to distinguish him, I suppose, from the galumphing, oppressively male human characters).

For the singers, human or animal, life is not so carefree. Sophie Bevan, as the Vixen (pictured right), makes characteristic light of music that, even when sung in Czech, makes the words dance more than it lets them sing, and that here, in Pountney’s new English translation, often seems to lie awkwardly on the voice. She gives, all the same, a vibrant, personable, acrobatic performance, with her lovely, easy production, and surprising agility about the stage. She reminds us, too, of her fine command of a brand of ecstatic lyricism, in her love scene with the Fox – a nice, stylish performance by Sarah Castle which doesn’t, nevertheless, quite convince me that Janáček was right to make him a soprano (to distinguish him, I suppose, from the galumphing, oppressively male human characters).

They in turn have few opportunities to sing out as they stumble myopically round the natural world. Jonathan Summers acts a plausible Forester, but his voice these days is on the dry side and lacks the warmth to lend his final apostrophe to nature the eloquence it deserves. Richard Angas provides a neat cameo of the priest with a clear conscience but a roving eye, Alan Oke is the dull schoolmaster still, in his dotage, regretting his gipsy love, David Stout the poacher who gets the girl and (with his shotgun) the Vixen. But Janáček wasn’t generous to them with his music; he warmed more to the male animals, the Dog (Julian Boyce), the Cockerel (Michael Clifton-Thompson), the Badger (Laurence Cole) – a series of memorable vignettes.

No advantage is taken of Janáček’s offer of part doublings, and as usual WNO crowd the stage with sharply observed individual performances, not least by children and dancers, too many to itemize, all excellent. Lothar Koenigs conducts, with a finesse worlds away from anything called for by Lulu, in its final performance the previous evening. And the orchestra switches style no less deftly, leaving aside minor issues of balance. For them the whole season has been a triumph.

- The Cunning Little Vixen at the Wales Millennium Centre on 26 and 28 February, then on tour

- Find other performances by Welsh National Opera

Add comment