It is almost an article of faith that over the 50 years since its first production, The Caretaker has become a classic of the British theatrical canon. Its carefully calibrated medley of deadpan, slapstick, and ennui, highbrow miserable-ism and low-pressure tragedy has evolved into a kind of Woolworths pick’n’mix from which subsequent writers for the stage, radio or television can select the bits they like, to confect something recognisably post-war British in generic mood and texture.

To apply the term “Pinteresque” might have made sense when we were all still digesting those key elements of his work that were radical and innovative. Now, we are all “Pinterised”; it would be hard to imagine contemporary culture without his input. The sinister but slapstick pass-the-parcel bag moment from the first scene of Act Two is now as classic as Edith Evan’s whooping “A haaanndbaaaag!!???” in The Importance of Being Earnest. His speech patterns, pauses and silences are now our theatrical default mode.

There is almost an element of the morality play in Morahan’s version

So, one might ask, since we dealing with a writer almost as hard-wired into our consciousness as Shakespeare, when are we going to see a production of Pinter set (say) in Dickensian London, or amongst Latinos in South Central Los Angeles? The answer seems to be, not yet. For the moment, we are sticking closely to the script. And to the canon. Who better then to interpet a faithful and conservative version of The Caretaker than veteran Pinter maven (he last directed the play in 1972), and former BBC Head of Plays, Christopher Morahan?

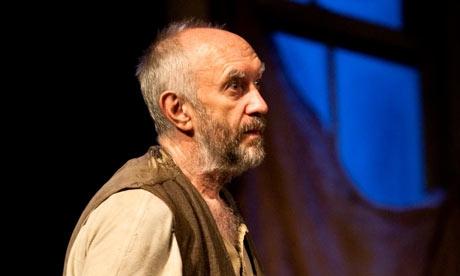

His surefooted – and already much garlanded - production arrives at the Trafalgar Studios directly from a three-month run at Liverpool’s Everyman Theatre, where local boy Jonathan Pryce received much acclaim for his incisive and profoundly rendered take on the creepy and disturbed drifter Davies. Although ably flanked by Peter McDonald’s ponderous, brain-damaged Aston and Sam Spruell’s wide(ish) boy on the make Mick, this is very much Pryce’s evening, the wattage generated by his jerky, unpredictable kinesis frequently greater than that from the dangling exposed lightbulb in the brothers’ miserable, junk-filled room.

And what junk it is: Eileen Diss’s set is a glorious confection, mounds of early 20th-century detritus lovingly and artfully arranged like great baroque swags round the front and the back of the stage. This isn’t just any old junk, mind: this is vintage junk, each 1940s paraffin stove and every pre-war wooden beer crate as perfect an articulation of Pinterland as the text of the play itself. Unlike those Britflick period dramas where every prop is sourced from the same year as the action itself, Diss’s props are – just like Pinter’s play - not to mention Davies’s stinking long johns and grubby smoking jacket, a well-honed palimpsest of successive decades of British domestic dreariness.

The sharp electric qualities of Pryce’s shifty, conniving drifter from Wales (this is played up by his accent, though it varies at times in moments of bitter mimicry), chattering in his sleep, and alternately threatening, cajoling and flattering his uneasy hosts, firmly root Morahan’s production in the present tense, while drawing implicitly on Pinter’s constantly inferred back story.

So while Spruell’s nervy, ambitious Mick strides around like a proto-rocker, projected into a (possibly unobtainable) imaginary future (of a made-over flat with trendy cork floorings and newly fitted kitchen cabinets), McDonald’s doleful older brother Aston mopes about in his dusty old demob suit and shabby mac, reliving with bruised dignity his traumatic experiences in an unspecified mental hospital.

Pryce’s livewire Davies acts the dexied-up psycho street-geezer (with flashes of some very contemporary body language), but his persona is rooted in his uncertain past, of soldiering (his illusive, all-important papers are in Sidcup, site of an erstwhile army base), and of having lived overseas: “Been to the colonies, have you?” - “Oh, I was one of the first over there”).

But there is almost an element of the morality play in Morahan’s version: whilst galvanising our attention, Jonathan Pryce’s Davies is an irredeemable bastard, who has bitten the hand that has been feeding him (literally, with the odd British Rail-looking cheese sandwich), and is about to be cast out into a biblical darkness where there will be no hope.

For most of the play, Sam Spruell’s Mick is brash, superficial and selfish, but in the last scene his (near) epiphany of affection and loyalty towards his dopey, “workshy” brother is carefully emphasised. Finally, it is Peter McDonald’s haunting Aston that triumphs after sundry humiliations and much turning the other cheek: looking sideways out of the window, his bruised, beta-male Brando-esque profile taking on for the first time a countenance of quiet authority, we learn that it is, even in Pinterland, the Meek who inherit the Earth. Quo vadis, St Harold?

- The Caretaker is at Trafalgar Studios 1 until 17 April. Book online.

Add comment