Was it right to censor Exhibit B? | reviews, news & interviews

Was it right to censor Exhibit B?

Was it right to censor Exhibit B?

A white artist recreates a 'human zoo'. Are we meant to be surprised at the blacklash?

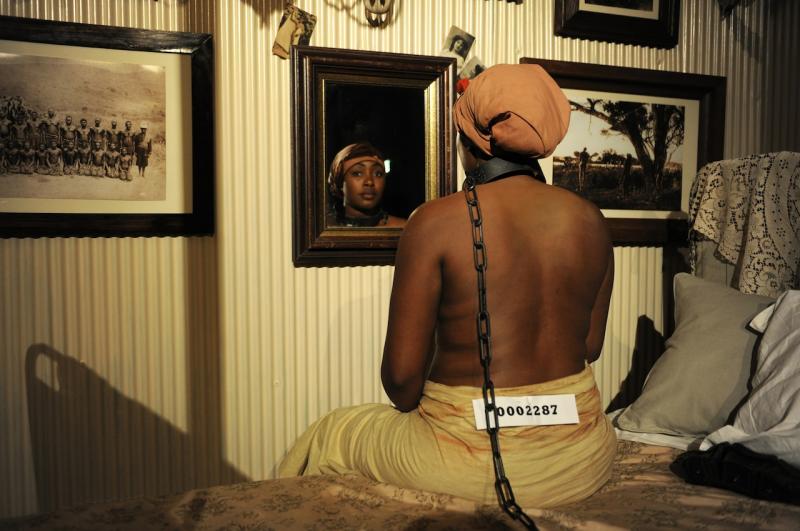

So, Exhibit B, the controversial “human zoo” using black actors to re-enact the role of ethnographic exhibits – semi-naked, chained, silenced by metal masks and degraded in metal collars – has been cancelled, due to the presence of protesters.

The piece, a series of tableaux vivants recreating the human zoos popular in Europe and America in the 19th and even the first decades of the 20th century, is a work by white South African artist and theatre-maker Brett Bailey, and was being staged by the Barbican. Most recently it had been seen at the Edinburgh Festival, where the reaction appeared to be overwhelmingly positive, at least as evidenced by the critics who wrote about it and those who left comments in the comments book. I was due to review it, but since I’m probably more interested in the ethical dilemmas such an art work throws up, rather than in actually experiencing it first-hand (though that would have been interesting, too), I’ve decided to write about it anyway.

It doesn’t take a lot of thought for the comparison between human zoos and gas chambers to break down

What’s especially interesting is why this particular form of art making – a theatrical art installation – addressing this particular aspect of black subjugation, fills so many with revulsion; by that I mean a revulsion directed at the work itself rather than its subject matter. The spokesperson for the protests, Sara Myers, said in an interview that no Jewish person would support a similar work enacting, for instance, the gas chambers for a paying, liberal and supposedly well-meaning Gentile audience. They would, she said, have too much self-respect to be so grotesquely re-objectified and dehumanised in this way.

She’s certainly not the first to imagine there can be no parallel work addressing that particular barbarity in recent Jewish history. And she’s almost certainly right. One cannot imagine an institution such as the Barbican staging that particular horror as an “artistic” tableau. But we also know there have been no end of films and plays, even paintings and an opera, addressing the Holocaust. The Holocaust has been artistically explored, perhaps exploited, in countless ways – even as comedy and satire. And as paying audiences we have indeed "entered" gas chambers, so that we may empathise with victims facing the almost unimaginable horror of their annihilation.

Bearing witness to horrific historical events through artistic representation is unquestioningly valued, but tellingly, what has largely been ignored, until very recently, is black history under white colonial rule. When Roots, the American TV saga adapted from Alex Haley’s blockbuster novel, was broadcast in the mid-Seventies it caused an absolute sensation, and it even created a folk hero out of one character called Chicken George. In many cases it was the first time white audiences had been confronted by this aspect of black history. Since then, there has been a slow trickle of important art works addressing the black holocaust, but nothing to compare to the Jewish experience. Mostly it has been a side issue of a “bigger” story about white American and European history.

So this leads back to the question: what is it about Exhibit B in particular that has made some 22,000 protesters sign an online petition against it? Are the objections valid, or is the Barbican caving into censorship?

Of course, it doesn’t take a lot of thought for the comparison between human zoos and gas chambers to break down, because the death camps and the gas chambers were never intended as public spectacles, but simply as an efficient means of genocide. Not only did the rest of the world not know about them, but they were never intended to draw the public’s complicity as spectators. And human zoos were. This really was a form of entertainment, presented in many cases as a pseudo-scientific “education” for white audiences. And, in my view, this gives Exhibit B a much stronger validity; there is a stronger case for saying that an art work directly addressing this might be important.

In fact, it’s not the first time a human zoo has been recreated as performance art. In 1992, two Cuban-American artists, Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña, sat in a cage dressed in a hybrid of “ethnic” tribal gear and Americana – Fusco in a grass skirt and a pair of Converse, Gómez-Peña in a leopard-skin wrestling mask (pictured right). Fusco could even be seen occasionally writing on a laptop. This was meant to raise questions of authenticity that Westerners often have about non-Western peoples, especially when it comes to our Rousseauian and somewhat condescending concerns about tribes being “corrupted” under bad Western influences. The artists were meant to represent a couple from a lost Mexican tribe who had been deracinated.

In fact, it’s not the first time a human zoo has been recreated as performance art. In 1992, two Cuban-American artists, Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña, sat in a cage dressed in a hybrid of “ethnic” tribal gear and Americana – Fusco in a grass skirt and a pair of Converse, Gómez-Peña in a leopard-skin wrestling mask (pictured right). Fusco could even be seen occasionally writing on a laptop. This was meant to raise questions of authenticity that Westerners often have about non-Western peoples, especially when it comes to our Rousseauian and somewhat condescending concerns about tribes being “corrupted” under bad Western influences. The artists were meant to represent a couple from a lost Mexican tribe who had been deracinated.

Needless to say, the satire was rather crude, but, astonishingly, as the performance travelled to various important venues across the States and in Europe (it was shown at the Smithsonion, Washington, as well as in Covent Garden in London) some people bought into it as a real human zoo; and although one lone spectator did write to the American Humane Society to object, there were certainly no protests. Spectators seemed happy to have their pictures taken alongside the two “primitives”.

But Exhibit B is very different in tone. It’s not meant to be a crude satire, though it does appear that it, too, is eager to point out the contradictions in Western belief systems. One important issue it raises is the connection between our historical abuse of black people and how we treat people of colour today – the installation also features black actors enacting a role as refugees. But since no one can now get to see it in London, there’s no way of telling if it draws these parallels successfully. Obviously, I can't write about Exhibit B as an art work, since I haven’t seen it; I can only write about it as an “issue”. And if this is simply a question of asking, "Is this issue something we can legitimately make art out of?", then the answer must, of course, be yes.

But still, all this does is ignore a more pressing concern, which is to do with black representation in the arts – the negligible number of black artists, and the almost complete absence of black arts directors and policy makers. The fact that the artist here is white, and even more damningly, it appears, the fact that he is a white South African, must have some bearing on how the piece has been perceived. The protests appear not to be a judgement about the art work itself – how can it be? – but about who has made it and who will go and see it.

What comes with this is the inevitable anger directed at a white artist, and a white institution, “appropriating” black experience. And although I’m not of the mindset, prevalent at the height of Nineties identity politics, that such artistic expressions must always be some kind of act of colonial, white supremacist exploitation, it does, unavoidably, become an issue when a white artist recreates a human zoo in which black people are once again objectified as less than human – and all the subtle and complex ingredients that make an art work important simply die under that narrow gaze.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment