Although he made his name with the generally upbeat grooves and licks of his Barrytown Trilogy, Roddy Doyle has often played Irish family and social life as a blues full of sorrow and regret. In his Booker-winning Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, a bitter parental break-up shadows the wee hero’s passage through childhood. Domestic violence and the self-medication found in booze fuel The Woman Who Walked into Doors and its sequel, Paula Spencer. Nowhere, however, has Doyle pushed his bantering, motor-mouthed Dubliners further down into darkness than in this latest novel.

The results may divide his fans. Until its final 20 pages, Smile shapes up as a bittersweet story, typically well-observed and smartly-voiced, of a middle-aged, moderately screwed-up guy whose separation and solitude sends him on a journey through memory towards the sufferings of his childhood. Then, for all the assurance that nothing “supernatural” has happened, the floorboards of social realism suddenly give way beneath our feet. Shockingly, we’re in an uncanny place that might have been furnished by Henry James at his spookiest. Other readers may find that another Dubliner comes to mind: Oscar Wilde, and The Picture of Dorian Gray.

Stuck in his nondescript post-divorce apartment in Dublin with (so he surmises) noisy Eastern European sex workers for neighbours, Victor Forde, now a fiftysomething singleton, revisits the past. A bright kid from a poor home, he has initially flourished as a slash-and-burn rock journalist who “became a bully” (as ever, Doyle gets the bands and sounds of a generation agob exactly right). Later, he prospers modestly as a radio interviewer and current-affairs pundit, always on tap for a mischievous slot winding up the politicians and the priests of conservative Ireland. We sense from the off that (hardly an unknown condition in his country) he has a knack for converting trauma into tales: “I’d made a story of it.”

His proudest yarn tells of his relationship with Rachel Carey, a “national treasure” who set up an all-women catering business and became an iconic media entrepreneur on a TV start-up show that blended the formulae of Dragons’ Den and The Apprentice. Doyle excels at the gauche kid’s dawning sense of wonder that this capable, sexy, grown-up woman actually wants him and cares about him: “I’d fallen in love with an adult.” He basks in their shared fame: “We were neck and neck, celebrity chef and your man on the radio”. They had one son, about whom we hear suspiciously little.

Now, alone again and brooding on his early years, he starts to hang out in Donnelly’s bar. There he catches up on the male camaraderie and semi-serious quaffing (four pints, no more) that he had skipped in the upmarket, progressive Dublin of his media and business contacts: “I felt I was going right back into the life I’d missed.” Back in the stark flat, schoolboy memories rattle that hard-won adult identity. Victor recalls thrashings and humiliations at the hands of his Christian Brothers teachers: in modern Irish fiction, though, that feels almost as inevitable as a nice soft day of rain. The French teacher, a frustrated bohemian, had told 13-year-old Victor that “I can never resist your smile”. That was, as Doyle puts it, “a line from a film, in a very wrong place”. Worse, Victor remembers one sexual assault, though only the one, by the Head Brother. Years ago, as revelations of clerical abuse began to convulse Irish society, he had even talked about it on the radio (afterwards, “I had to vomit and shit”).

Now, alone again and brooding on his early years, he starts to hang out in Donnelly’s bar. There he catches up on the male camaraderie and semi-serious quaffing (four pints, no more) that he had skipped in the upmarket, progressive Dublin of his media and business contacts: “I felt I was going right back into the life I’d missed.” Back in the stark flat, schoolboy memories rattle that hard-won adult identity. Victor recalls thrashings and humiliations at the hands of his Christian Brothers teachers: in modern Irish fiction, though, that feels almost as inevitable as a nice soft day of rain. The French teacher, a frustrated bohemian, had told 13-year-old Victor that “I can never resist your smile”. That was, as Doyle puts it, “a line from a film, in a very wrong place”. Worse, Victor remembers one sexual assault, though only the one, by the Head Brother. Years ago, as revelations of clerical abuse began to convulse Irish society, he had even talked about it on the radio (afterwards, “I had to vomit and shit”).

Victor, so he believes, has confronted and overcome the trauma. He worries, all the same, that he has sanitised the misery, turning it into “an expected part of every Irishman’s education. A bit of a gas. Not so bad. Part of what we are.” At the local, though, a gruff lunk by name of Fitzpatrick claims to have known Victor at school. He presses harder, deeper, into the hidden zones of pain. We learn more about the damaged Brothers – not only the molesters and the sadists, but the obsessives and the depressives – and their cast-iron impunity: “The Brothers knew they were safe.” Fitzpatrick’s bluff mateyness, we see, scarcely covers a seething cauldron of loneliness and anguish. Their bar-stool sparring and jousting leaves wounds on Victor, although – as always with Doyle – the beautifully paced, rippling flow of the dialogue (“the rhythm of the middle-aged Dub”) can fool unwary readers into believing that this bonhomie doesn’t conceal shards of glass within the stout-smooth craic.

The climactic reveal, or transformation, will either leave you purring with a satisfying sense of doors unlocked and clues resolved, or fuming at a drastic change of mode, even genre, that the author should have signposted earlier. On balance, I felt that the shock of this last-gasp shift simply made too much noise. Doyle’s screeching turn into a more Gothic domain served, for this reader, to blunt the keen insight of what had gone before – not least, into the way that Irish society has “processed” the exposure of mass institutional abuse and its cover-up without truly managing to lay those howling ghosts to rest. No one, though, could accuse Doyle of playing the same much-loved riffs one more time. With those eerie, closing chords, he changes not just his key, but his whole instrument.

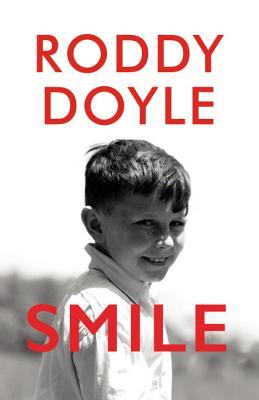

- Smile by Roddy Doyle (Jonathan Cape, £14.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment