Liminal: a word that conjures thresholds and between states. Caught between three languages – the adjective is a borrowing from the Latin that enters English by way of German – liminal also has three distinct definitions.

There is the underused sense: to produce “minimal” effect or when “a sensation becomes too faint to be experienced”. The more ubiquitous definition: being “transitional or intermediate between two states, situations”, or “characterised by being on a boundary or threshold”. Lastly, there is liminal’s cultural anthropological meaning, as when a person is between two “culturally defined stages of a person’s life… as marked by a ritual or rite of passage.” All three senses of the word burrow deep, past skin, nerve and bone, in Don’t Let It Get You Down, as Savala Nolan comes to terms with what it means to exist in, write from and give voice to the liminal.

Nolan situates the entire essay collection in the word’s most familiar adjectival sense. We begin in the intermediary imaginary, in the declassified spaces between classifications and cultural categories: between “Black and white… rich and poor… thin and fat (as a woman)”. To be positioned “betwixt and between” these dominant demarcations – between hegemonic constructions we recognise to be as destructive as they are life-giving – is to be missed, neglected, marginalised and often othered. To speak from this liminality, however, is a radical act of self-definition, self-determination, self-reclamation and resistance. From the offset, Nolan’s voice rears up from the cracks in these artificially constituted formations; her words gain power when coming from the side-lines, holding court on the thresholds, stealing in from the indeterminate and intermediate interstitial spaces she so powerfully reclaims and, with each essay, vibrantly owns.

When writing from the interstices of selfhood, Nolan generously shares the simultaneous pain and pleasure, anxiety and excitement, power and oppression that such positionality entails. In “On the Sources of Cultural Identity”, we experience Nolan’s joy in what an Ivy League education, her abounding desire for knowledge and her excellence in learning, affords: a year-long exchange programme in Italy. Perfecting Italian to the point of local fluency, visiting the Trevi Fountain and the Villa Borghese, experiencing “racelessness in the way white people do” as a mixed-race Black woman, and living la dolce vita defines her time there – at least for a while. But slowly, the repeated question “What are you?” (Qual è la tua etnia?) grates, as does the ignorant reduction of African American identity to televisual performativity and stereotypes; and the anti-Black hostility she experiences from the mother of her Italian boyfriend assaults both her body and the near-to-bursting bubble that is her Roman holiday. That this Italian odyssey allows her to excel at one romantic language at the expense of another – the Spanish that her Black Mexican paternal-side of her family speak – not only demonstrates the continued liminality Nolan personally navigates and negotiates within herself, but also highlights the cultural and psychological erasure society expects; the subtle sacrifices hegemonic cultures imperialistically demand in order for “mixed” individuals to be “acceptable”, though never fully accepted.

When writing from the interstices of selfhood, Nolan generously shares the simultaneous pain and pleasure, anxiety and excitement, power and oppression that such positionality entails. In “On the Sources of Cultural Identity”, we experience Nolan’s joy in what an Ivy League education, her abounding desire for knowledge and her excellence in learning, affords: a year-long exchange programme in Italy. Perfecting Italian to the point of local fluency, visiting the Trevi Fountain and the Villa Borghese, experiencing “racelessness in the way white people do” as a mixed-race Black woman, and living la dolce vita defines her time there – at least for a while. But slowly, the repeated question “What are you?” (Qual è la tua etnia?) grates, as does the ignorant reduction of African American identity to televisual performativity and stereotypes; and the anti-Black hostility she experiences from the mother of her Italian boyfriend assaults both her body and the near-to-bursting bubble that is her Roman holiday. That this Italian odyssey allows her to excel at one romantic language at the expense of another – the Spanish that her Black Mexican paternal-side of her family speak – not only demonstrates the continued liminality Nolan personally navigates and negotiates within herself, but also highlights the cultural and psychological erasure society expects; the subtle sacrifices hegemonic cultures imperialistically demand in order for “mixed” individuals to be “acceptable”, though never fully accepted.

In fact, Nolan’s candid exploration of her own self-erasure because of and through her proximity to whiteness bookends the collection. In “On Dating White Guys While Me”, Nolan powerfully exposes white male exploitation and the fetishisation of Black female bodies whilst also examining her own internalisation of the white male gaze; in “Little Satin Bomber Body”, meanwhile, she expertly encapsulates and elegantly debunks white Eurocentric and fat-phobic beauty ideals by discarding a “Gwen Stefani-esque” garment. In locking off said white men and the male gaze she once desired, and disposing of such toxic ideals by donating the bomber jacket to the charity Goodwill, Nolan asserts her body, her sexuality, and her identity as a fat African American and Mexican woman who no longer needs to view herself through a white Eurocentric lens. Asserting this position – one born of having to endure and confront continual denigrations from the margins – does not move her away from the liminal; rather, it empowers liminality and those whose lives and identities do not fit neatly into one census box over another. It recreates and resets the limits, spaces, standards and visual fields she has been forced to occupy. And it encourages us to examine our own participation in the manifold myths of hegemony – particularly those of white supremacy (even when carefully concealed in a size 0 satin bomber).

For Nolan, it is often these myths of whiteness that chime with the first sense of the word “liminal”. That racism and racial acts of violence still have a minimal impact culturally, politically and legally demonstrates the attitude and stance of unfeeling that moves through the white western world today. The titular essay of the collection, “Don’t Let It Get You Down”, pits this liminality of white affectivity (the minimalism of sensation, reaction and action) against the deep-rooted feelings of Black and brown individuals in the face of racial violence and police brutality. Yet when her Black hairdresser replies “Don’t let it get you down” to Nolan after she has read out a headline on her phone (announcing that the police officer who shot 12-year old Tamir Rice will not face charges), we know this form of the liminal, this form of unfeeling, can and must be used by African American communities in order to survive.

Yet survival through disaffection and emotional protection is not a form of the liminal that Nolan’s collection always espouses. Thriving through the intermediary imaginary, through cultural recreation and emotive literary reconnection to the past, however violent, comes to life in her stunning narration of her African American ancestors: the three Black women enslaved by her white fifth-great grandfather on her maternal side. Using the “pleasure” of her imagination in “To Wit, and Also” – the same imagination that springs from and celebrates Black creativity throughout the collection – Nolan reconstructs the lives of Filliss, Grace and Peggy, and reserves a “shaded” place (again, the half-light and half-state of the liminal) for them in her life today. For it is in the shaded spaces and dimly lit intervals of life that we’re paradoxically able to make sense of the various parts of ourselves and our equally heterogenous (and often horrific) histories – not everything makes sense or heals in the broad light of day.

That Nolan gifts us revelations fought for from within liminal spaces, stages and situations of her own life is, in itself, a silent ritual, a rite of passage of the essay form itself. Weaving popular cultural references into her own stories and those of her father and wider family, and citing musicians like Kanye and Mos Def through to artists like Kandinsky and Michelangelo, Nolan proves a pro at traversing liminal’s third anthropological sense. As an essay writer who entwines the non-fictional facts of her life with near-fictional masterpieces, she joins some of the greatest African American writers who have also written from the liminal to make their stories heard. Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Maya Angelou, bell hooks, although they were also novelists or theorists, all made use of the essay form, revelling in its capacity for articulating the intermediary imaginary, for making seen the interstitially positioned experience. Like these women, Nolan speaks power from and on the margins; in doing so, she inherits a tradition of storytelling that centres the experiences of Black women, whether big or small, mixed or poor, or betwixt and between these polarities. Finding her voice, her faith, her self in the liminal, Nolan reclaims a mighty tradition and way of telling for us all.

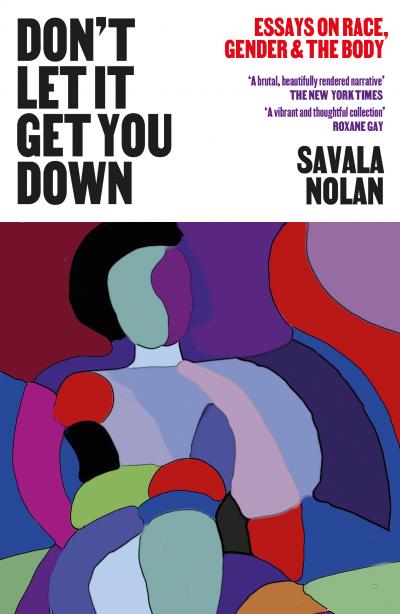

- Don't Let It Get You Down: Essays on Race, Gender & the Body by Savala Nolan (The Indigo Press, £12.99)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment