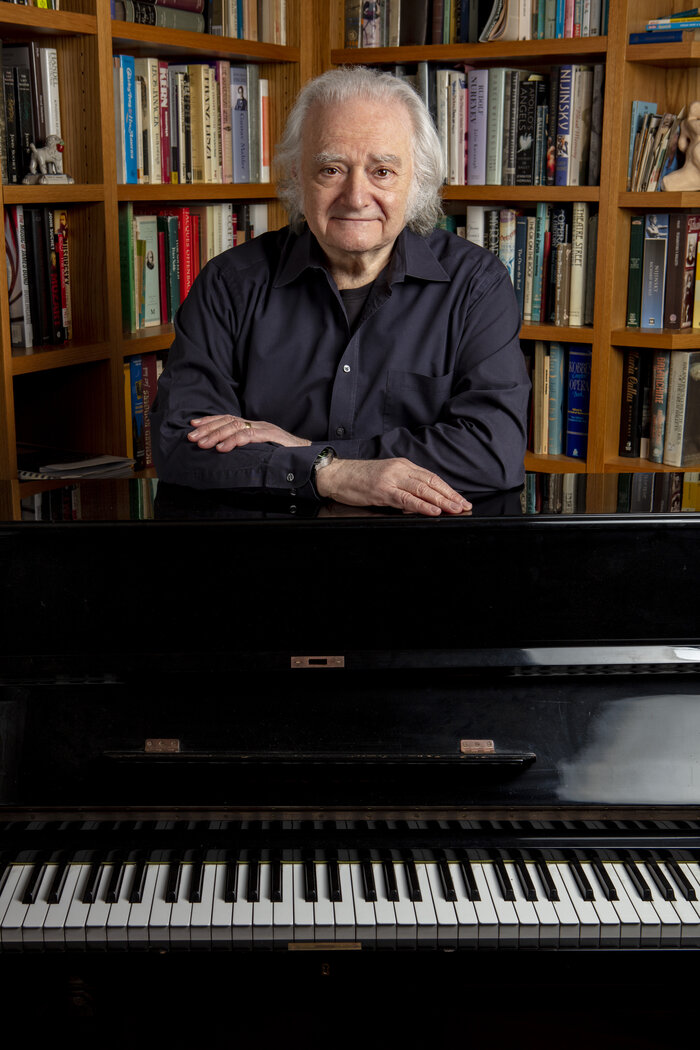

Composer and conductor Carl Davis, 1936-2023 | reviews, news & interviews

Composer and conductor Carl Davis, 1936-2023

Composer and conductor Carl Davis, 1936-2023

theartsdesk Q&A from 2021 with the silent film specialist on shot lists, bass drums and projection speeds

May 2021 should have seen the appearance on Netflix of a new restoration of Abel Gance’s silent epic Napoleon, lasting nearly seven hours and timed to coincide with the 200th anniversary of Napoleon’s death. The release was delayed, but, in anticipation, theartsdesk spoke to the composer and conductor Carl Davis, who has died aged 86.

GRAHAM RICKSON: I became aware of your name in the 1980s, when the Thames Television series was being broadcast, and I’d seen snippets of The World at War.

CARL DAVIS: The earlier series premiered in 1972. It’s still being shown! The live aspect of composing for complete silent films began with a showing of Napoleon . That changed everything – for me, for the curators and for the public. The very idea that you could show a film like that, in a sizeable venue to a large audience. It sent out a lot of arrows.

How did you become interested in silent cinema?

I was nine years old at a summer camp, where they showed a Chaplin short with someone hacking away at a piano. Even at that early age, something must have clicked – I had the concept in my mind. Then I came to London from New York in 1960, and the National Film Theatre was the only place which then showed silent films, with an improviser on piano. My active involvement started in the late 1970s when I was commissioned to write music for a Thames Television series called Hollywood: A Celebration of the American Silent Film. It was based on a book by film historian Kevin Brownlow. A fan of that book was producer Jeremy Isaacs, who at the point we met had just produced The World at War. His next plan was to given Brownlow a chunk of money to go to Hollywood to catch all those involved in silent films who were still around - the actors, the technicians, the writers, and to do it while they were still capable of talking! I was shipped out to track down the musicians, some of whom were still playing in old age. That series blew things wide open, creating a surge of interest in silent cinema.

Not thinking that much would happen after that, I mentioned to colleagues that I’d written music for 300 silent film clips and that I’d like to score a complete film. The initial plan was to present a one-off screening of Abel Gance’s Napoleon (pictured, right) which the director never completed. In 1980 we ended up with just under five hours, as assembled by Brownlow. We chose to combine film, orchestra and audience at the Empire Leicester Square, which had originally been a silent cinema. That first screening wasn’t flawless, but it was still electrifying. It opened the wave. Isaacs went on to found Channel 4, and we kept looking at Napoleon, which was growing. Extra footage was discovered when it was the 20-year anniversary. That film won’t lie down!

Not thinking that much would happen after that, I mentioned to colleagues that I’d written music for 300 silent film clips and that I’d like to score a complete film. The initial plan was to present a one-off screening of Abel Gance’s Napoleon (pictured, right) which the director never completed. In 1980 we ended up with just under five hours, as assembled by Brownlow. We chose to combine film, orchestra and audience at the Empire Leicester Square, which had originally been a silent cinema. That first screening wasn’t flawless, but it was still electrifying. It opened the wave. Isaacs went on to found Channel 4, and we kept looking at Napoleon, which was growing. Extra footage was discovered when it was the 20-year anniversary. That film won’t lie down!

Watching the restored print of Buster Keaton’s Steamboat Bill, Jr. with your score is a little like following a seamless full-length ballet.

Yes - the relationship between film and ballet is striking, and I find myself composing more and more ballet scores now, something which the film work has made me much better at. Though in ballet, you have to give the dancers more time; with film you have cuts. Though both are narratives, both genres have stories. I ask myself what is the film about – a romance, a war film, a comedy? If it’s based on something, I do my research. The first important question has to be ‘”is there a budget’? Can I use lots of players? With an epic like Ben Hur or The Thief of Baghdad (pictured, above left), you can’t cheat. But with a comedy, you don’t need 80 players – it can work with just a piano. I prefer having an ensemble though.

Yes - the relationship between film and ballet is striking, and I find myself composing more and more ballet scores now, something which the film work has made me much better at. Though in ballet, you have to give the dancers more time; with film you have cuts. Though both are narratives, both genres have stories. I ask myself what is the film about – a romance, a war film, a comedy? If it’s based on something, I do my research. The first important question has to be ‘”is there a budget’? Can I use lots of players? With an epic like Ben Hur or The Thief of Baghdad (pictured, above left), you can’t cheat. But with a comedy, you don’t need 80 players – it can work with just a piano. I prefer having an ensemble though.

The film has to be measured. How long do the chases and love scenes take? I make myself a map, a 'shot list’ and have a notebook with the timings, so I know what space I have to cover. What is a scene’s character, and where is it in the film? With a silent film, you’re plugging a huge gap with music. Sometimes I use sound effects – a pratfall in a comedy can be suggested with a bass drum. I treat any sound effects as elements of the score. With a contemporary film, there’s always a lot of discussion about where the music will be needed. With a silent film, and this is a great release for me, the music has to cover every scene! If you do have silences, they have be of great significance.

Your output is huge; it’s as if you’ve written several Ring Cycles! Can you sum up the differences between conducting a recording in a studio, and leading a live orchestra in a cinema?

The merit of recording is that you can do it again! One shock comes when you conduct these things live, and realise that you can’t go back. You have to keep going. Some conductors use click tracks and headphones. I’m old fashioned and don’t like being tied to machinery – I try to conduct these things with as little apparatus as possible. We can all agree when we’re going to start, and then it’s in my hands.

A ballet conductor friend described to me how the speed of a performance can vary according to how tired the dancers are, or the time of day.

Yes – when conducting ballet you have to have a rapport with your dancers. With live film, that’s never the case. The film is god. You might be tired, excited or nervous, but you have to be rigid. What does have to be agreed on is the projection speed. Things are easier now as more and more screenings are digital. There’s no faster or slower; it’s what it is. When you’re dealing with a 35mm print, the speed can vary, and that’s when you’re in trouble! If it’s being shown too fast, or too slow, ideas about synchronisation go out of the window. I always ask how a film is going to be projected.

Your work must be a little like restoring a painting? I’m struck by how much your scores respect an individual film’s genre and historical setting.

Yes. I don’t want to impose. I try to be at one with the film, and don’t want to add something which could spoil it. There are some films that transcend their time of creation, which are ahead of their time and don’t feel like products of the 1920s. Like Eric von Stroheim’s Greed (pictured, right), or Victor Seastrom’s The Wind. The feeling can be very contemporary, so I can bring in 20th century sensibilities, with more dissonance that might have been allowed at the time. I’m a respecter. If the costumes and sets reflect a period, I’ll go with that.

Yes. I don’t want to impose. I try to be at one with the film, and don’t want to add something which could spoil it. There are some films that transcend their time of creation, which are ahead of their time and don’t feel like products of the 1920s. Like Eric von Stroheim’s Greed (pictured, right), or Victor Seastrom’s The Wind. The feeling can be very contemporary, so I can bring in 20th century sensibilities, with more dissonance that might have been allowed at the time. I’m a respecter. If the costumes and sets reflect a period, I’ll go with that.

Where did your fluency come from, this ability to write so much, so quickly?

From childhood on, I was immersed in opera. Every Saturday afternoon in New York, I would listen to a broadcast from The Met. I was glued to the radio. I would make sure I had a score, borrowed from the public library. When I started piano lessons, I would play from the opera scores which I knew. So when I arrived in England at the age of 23, I already had an operatic feel, understanding that the drama lay in the score. Composing a long, romantic score can be like writing a Puccini opera. The emotions and colour are all in the orchestra. I dived in as a child, discovering how music could express emotion, mood and setting.

Are there particular projects which are still on your ‘to do’ list?

Oh yes. Every once in a while, a little door opens and someone asks me to play for a particular film which I might not have seen, but I end up realising that it’s fabulous. There’s still a vast amount of product from the silent era. Much was destroyed when sound came in, but there’s still a lot which survives. Conducting film scores has become an industry. It’s not just me – it’s become competitive! Incredible when I look back to where we were in 1980. Sadly, with the pandemic, it’s all come to a halt. I’ve had lots of performances cancelled as I can’t do any conducting. Instead, I’m busy with collections of piano pieces, and I’m reissuing my older recordings, I’ve just released a ballet score based on The Great Gatsby, full of tangos and dances. In a way, I’m quite occupied at the moment. Luckily I’m not dependent on my physical body. There’s no time limit to writing and conceiving music!

Oh yes. Every once in a while, a little door opens and someone asks me to play for a particular film which I might not have seen, but I end up realising that it’s fabulous. There’s still a vast amount of product from the silent era. Much was destroyed when sound came in, but there’s still a lot which survives. Conducting film scores has become an industry. It’s not just me – it’s become competitive! Incredible when I look back to where we were in 1980. Sadly, with the pandemic, it’s all come to a halt. I’ve had lots of performances cancelled as I can’t do any conducting. Instead, I’m busy with collections of piano pieces, and I’m reissuing my older recordings, I’ve just released a ballet score based on The Great Gatsby, full of tangos and dances. In a way, I’m quite occupied at the moment. Luckily I’m not dependent on my physical body. There’s no time limit to writing and conceiving music!

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment