Bruckner: Symphony No. 7 Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich, Paavo Järvi (Alpha)

Bruckner: Symphony No. 7 Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich, Paavo Järvi (Alpha)

Parsifal Suite London Philharmonic Orchestra/Andrew Gourlay (Orchid Classics)

There are many things to like about this sleek performance of Bruckner 7. The playing of the Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich under Paavo Järvi is polished, and the speeds are well-chosen, Järvi especially good at managing the transitions between the different blocks of music. He’s blessed with a fabulous brass section, and it’s a joy to hear the tuba quintet at the start of the “Adagio” singing so clearly, the individual voices so well delineated. Järvi sensibly includes the cymbal crash and triangle at the movement’s climax, and the funereal coda is haunting. Badly-handled Bruckner can feel perfunctory and dull; Järvi’s players sound like true believers. Those shifting brass chords before the percussion enter are spine-tingling here, Järvi cannily tightening the screws so that the big C major moment really hits home. The rest is good too, the scherzo’s folksy stomp fast and furious, the quirky finale hanging together nicely. Alpha’s engineering, the work taped live in January 2022, is suitably rich.

All of which prompted me to investigate conductor Andrew Gourlay’s Parsifal Suite, a glowing seven-movement work lasting 47 minutes in this performance. The prospect of four and a half hours of uncut Wagner fills me with trepidation, so what booklet essayist Joanna Wyld describes here as “judiciously pruned excerpts” sound pretty wonderful to me; I’ve added getting to know the complete opera to my list of this year’s jobs. Gourlay’s London Philharmonic play like gods, bringing out the score’s very distinct character. This is Wagner dripping with soul, without a hint of bluster. The “Prelude” unwinds like a Bruckner adagio and there’s some sublime string playing at the start of the Act 3 transformation music. Lower brass roar in the Act 2 prelude, and Gourlay’s digitally created church bells are highly effective in the second section. It flows beautifully. Gourlay’s score is available for perusal on the publisher Schott’s website. Do investigate – this is a beautiful disc.

All of which prompted me to investigate conductor Andrew Gourlay’s Parsifal Suite, a glowing seven-movement work lasting 47 minutes in this performance. The prospect of four and a half hours of uncut Wagner fills me with trepidation, so what booklet essayist Joanna Wyld describes here as “judiciously pruned excerpts” sound pretty wonderful to me; I’ve added getting to know the complete opera to my list of this year’s jobs. Gourlay’s London Philharmonic play like gods, bringing out the score’s very distinct character. This is Wagner dripping with soul, without a hint of bluster. The “Prelude” unwinds like a Bruckner adagio and there’s some sublime string playing at the start of the Act 3 transformation music. Lower brass roar in the Act 2 prelude, and Gourlay’s digitally created church bells are highly effective in the second section. It flows beautifully. Gourlay’s score is available for perusal on the publisher Schott’s website. Do investigate – this is a beautiful disc.

John Cage: Choral Works Latvian Radio Choir/Sigvards Kļava (Ondine)

John Cage: Choral Works Latvian Radio Choir/Sigvards Kļava (Ondine)

I had absolutely no idea what to expect from a CD of John Cage choral music. He’s not really associated with this often conservative genre, and only came to writing choral music in his 60s. And of the four pieces here, only two are actually designed for voices – the others have open scorings which happen to work vocally. Also, interestingly, for a composer with this self-professed blind-spot, these pieces show a late engagement with the world of harmony. Hymns and Variations takes two hymns by an 18th century American composer and bleaches the tonality out of them, some notes deleted while other notes are stretched, so meditation meets unpredictability with a kind of Feldman-meets-Pärt result. My favourite piece is the opener, Five, from 1988 (Cage died in 1992): the droning notes are coloured with overtones and a rich, evolving dissonance.

The 30-minute-long Four6 adds a wider range of vocal effects to the mix, an evocative texture where the sustained notes dissolve into trills, swells, warbles and Morse-code-like rhythmic patterns – I swear I even heard a pretty convincing “miaow”. It’s a bit like Bartók’s “night music” translated into a strange animalistic soundscape. The adventurous Latvian Radio Choir are fully committed and immerse themselves in this peculiar music. It’s strange, for sure, but utterly compelling. – Bernard Hughes

Songs by Warlock and Howe Anna Harvey (mezzo-soprano), Mark Austin (piano) (Rubicon)

Songs by Warlock and Howe Anna Harvey (mezzo-soprano), Mark Austin (piano) (Rubicon)

The title of this CD sounds like a boast about its quality: “Warlock, and how!” In fact, the Howe is Frederick Howe, a British composer (b.1951) whose folksong arrangements here complement a selection of solo songs by Peter Warlock. Howe says he hears folksong features in Warlock, where other commentators feel he owes less to that tradition than others of his generation – say, Butterworth, or Gurney. This album makes a plausible case. The 21 Warlock songs include two getting their premiere recording. “Little Trotty Wagtail” is perky, the piano part articulated with great character by Mark Austin. The poem of “The Magpie” tells of a thwarted romance, with fairytale overtones – and a hint of #MeToo – and is dispatched vigorously by Anna Harvey, who elsewhere finds a languor (“Late Summer”) and poignant archaism (“The First Mercy”). “Adam lay ybounden” is better known in its later choral version, but I’m not sure I don’t prefer this voice-and-piano original, performed with subtle give-and-take between singer and pianist.

Frederick Howe’s songs are enjoyable, if modest in ambition. Stylistically there is nothing there that mightn’t have been written by Warlock, and there isn't the strong identity of Britten’s folksong arrangements. But the impressionistic “The Banks of Sweet Primroses” is delightful, Harvey’s line beautifully controlled, and “Geordie” has a similar approach to Judith Weir’s Scotch Minstrelsy. – Bernard Hughes

Harpsichord Concertos by Martinů, Krása and Kalabis Mahan Esfahani (harpsichord), Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra/Alexander Liebreich (Hyperion)

Harpsichord Concertos by Martinů, Krása and Kalabis Mahan Esfahani (harpsichord), Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra/Alexander Liebreich (Hyperion)

The harpsichord is difficult to balance against a modern orchestra, and it’s fun hearing how three 20th century Czech composers approach the challenge. Martinů’s 1935 Concerto for harpsichord and small orchestra is an effervescent jewel, the soloist pitted against a small ensemble including piano. Hearing the two keyboard instruments conversing in the pithy first movement is a delight. The six-minute finale is echt-Martinů, opening like a concertino for piano and chamber orchestra before soloist Mahan Esfahani enters, immediately racing off at a tangent. If you love this composer (if you don’t, you really should), this disc is mandatory listening. Then there’s the Kammermusik for harpsichord and 7 instruments, written in 1936 by Hans Krása. Krása’s flourishing career was cut short upon his arrest by the Nazis in 1942; he was sent to the Theresienstadt Ghetto and was murdered at Auschwitz two years later. The Kammermusik is immediately appealing: just two movements lasting less than 15 minutes, Stravinsky and Weill among the influences (check out the second movement’s haunting bluesy opening). Three clarinets and an alto saxophone give the work its character, the harpsichord more of an ensemble player than a soloist.

Viktor Kalabis was the composer husband of the great Czech harpsichordist Zuzana Růžičková. She died in 2017, and Esfahani was her last pupil. Kalabis’s Concerto for Harpsichord and String Orchestra dates from 1975 and was dedicated to his wife. The pair collaborated on the work’s first recording (still available on Supraphon); Esfahani’s reading is fractionally slower but no less incisive. This large scale, three-movement work is a masterpiece. Serious, playful and gravely beautiful by turns, Esfahani sees it as a reflection of the couple’s relationship. The finale’s close is magical, Kalabis eschewing fireworks for something more mysterious and introspective. This is a wonderful anthology, brilliantly performed and recorded, with Alexander Liebreich’s Prague Radio Forces providing taut, colourful support.

Kaiju Crescendo – An Evening of Japanese Monster Music (Supertrain Records)

Kaiju Crescendo – An Evening of Japanese Monster Music (Supertrain Records)

Two discs of music taken from Japanese monster movies. What’s not to love? Well, the minimal sleeve notes (white on a black background) are near-impossible to read, and the playing of the pick-up orchestra has a few rough edges. Otherwise, this is a highly enjoyable collection. "Kaiju" is the generic Japanese term for giant monsters, and this fan-funded album was taped at a 2019 concert in Stokie, Illinois, conducting duties shared between composers John DeSentis and Michiru Oshima. It’s fun to hear excerpts from the great Akira Ifukube’s 1950s Godzilla score, the offbeat brass and percussion thwacks paying homage to Stravinsky’s “Augurs of Spring”, and the opening to the flying dinosaur epic Rodan is a soft, impressionistic cloud of sound. Not for long, though; things get noisier very quickly and there’s plenty more Stravinskian pastiche. We get cues from Masaru Sato, famed as a long-time Kurosawa collaborator. 1967’s Son of Godzilla opens along Ifukubian lines before taking a left turn into late 60s lounge music. It’s nuts, but irresistibly so. A suite from Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla follows a similar path, vocalist Meghan Guse blasting out an untranslated power ballad along the way.

Oshima’s compositions fill the second CD. Her first kaiju soundtracks date from the early 2000s and follow a similarly noisy and brassy template, though I missed the quirkiness of the Sato cues. Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla includes an appealingly schmaltzy love theme before the whooping horns return. Guse’s vocalise in Godzilla: Tokyo SOS is a nice touch. Trailers and extended clips from most of the films are available on YouTube. A winner.

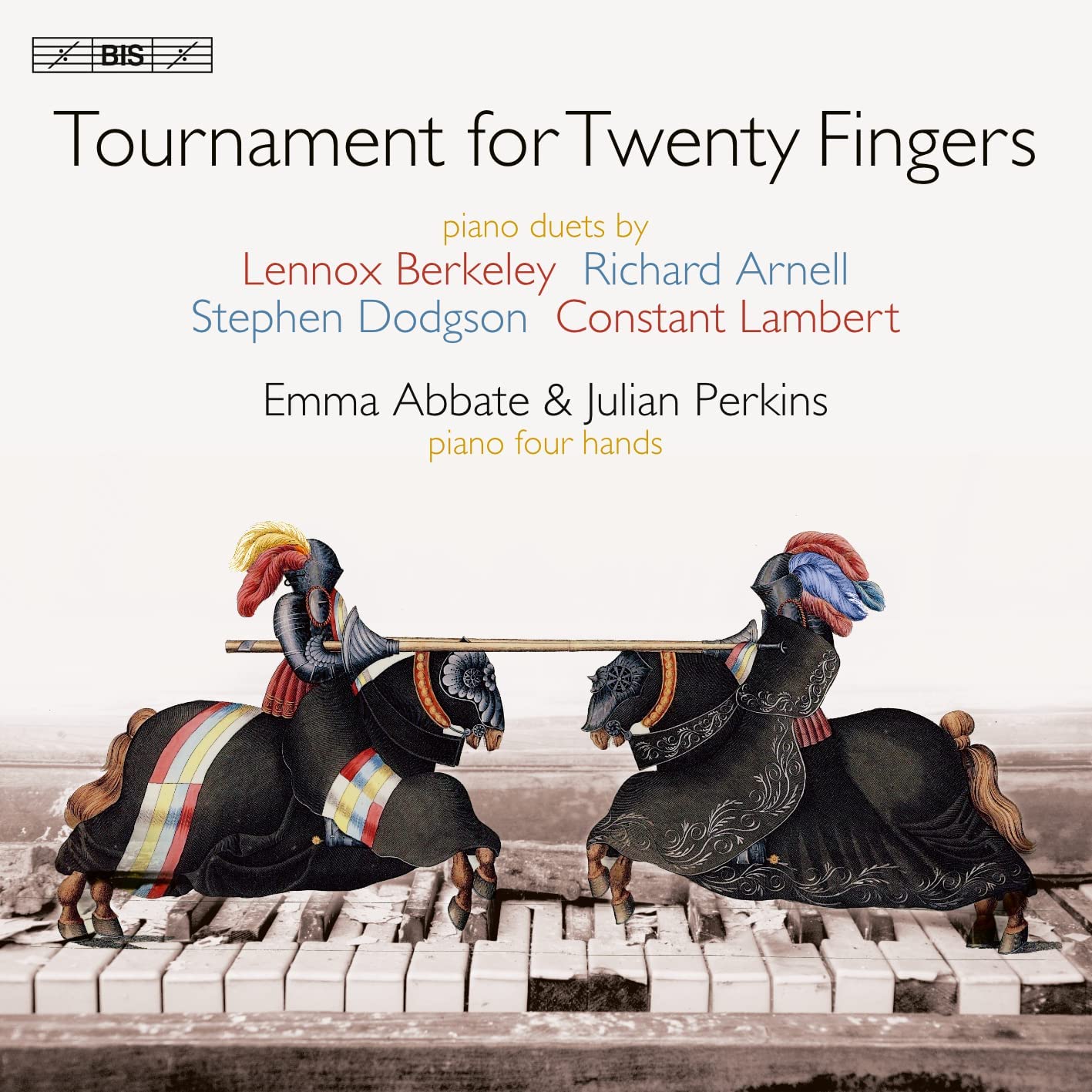

Tournament for Twenty Fingers – Piano duets by Lennox Berkeley, Richard Arnell, Stephen Dodgson and Constant Lambert Emma Abbate and Julian Perkins (BIS)

Tournament for Twenty Fingers – Piano duets by Lennox Berkeley, Richard Arnell, Stephen Dodgson and Constant Lambert Emma Abbate and Julian Perkins (BIS)

This album has already been out for a few months now, and the BIS label may have already moved into its 50th year celebrations (Skål and above all Tack så mycket!)... but this collection certainly deserves some attention. The four-hands piano duo Emma Abbate and Julian Perkins have taken the trouble to understand this repertoire; they are able to tell a totally convincing story with every piece. They have performed the album's 1952-4 title work, a seven-piece sequence by Stephen Dodgson (1924-2013), several times in concert (and to the composer when he was alive), and are completely alert to its well-crafted charm. They give the work its premiere recording here, and have built a fascinating programme around it. Most of the pieces in Dodgson's "Tournament" are characterful, short, and light-footed. The last of them, "A Bohemian Entertainment" carries a dedication to Dvořák and is delightfully melodic and, under Abbate and Perkins's hands, exquisitely paced. The 1949 Dodgson Sonata is more weighty, and starts and ends in thoughtful mode.

There is a fascinating "Sonatina" by Richard Arnell, dedicated to George Balanchine, plus some delightful jazz-inspired pieces from Constant Lambert. I have found myself, above all, going back to the three works by Lennox Berkeley which show his range: from a Satie-esque "Palm Court Waltz" to a knottier "Sonatina", probably from 1954, to the amazing sense of light versus shade, dense counterpoint versus simplicity and natural expression of a “Theme and Variations” from 1968. That might be the masterpiece lurking in this collection. Stephen Johnson's excellent programme note sums up one of the Berkeley works with the sentence "seriousness is constantly balanced with playfulness.” Abbate and Perkins always find ways to strike that balance, and do so exquisitely. – Sebastian Scotney

Add comment