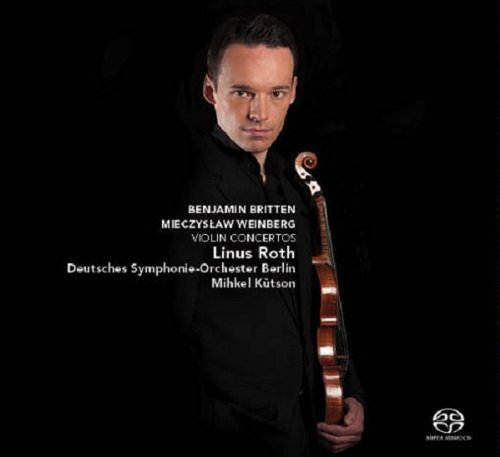

“I am a pupil of Shostakovich. Although I have never had lessons from him, I count myself as his pupil, as his flesh and blood.” Mieczysław Weinberg's close, complex relationship with his senior mentor continues to affect how we perceive his own music. Which is maddeningly inconsistent, and the jury's still out as to whether he's one of the great Soviet composers. But, when Weinberg is on form he can be terrific, and this 1959 Violin Concerto is a magnificent beast. It contains everything – dynamism, rhythmic punch and soaring lyricism. You'd be a chump not to find this work thrilling. If any performer can popularise the piece it has to be the phenomenal Linus Roth, whose unflagging energy makes this CD one of the best concerto discs in years. He's marvellous from the off – Weinberg's Allegro molto first movement unfolds with steely exuberance, accompanied with punch and swagger by Mihkel Kütson's Berlin forces. There's an exquisite slow movement, and the dry wit of the finale is transformed into something warm and bittersweet. The closing seconds are a joy. With Shostakovich, the humour is invariably ironic and sardonic; Weinberg's style is more conciliatory. We've all got favourite neglected works, but this one really does deserve to be better known. A masterpiece? Yes – trust me.

Roth also includes a stunning account of Britten's more familiar concerto. He's a touch more solemn than the superb James Ehnes, helped by gloriously rich, dark-toned orchestral playing which has the effect of placing the piece more firmly in the central European tradition. There's a wonderful lyrical passage six minutes into the first movement – it's extraordinary here, Roth and Kütson making time stand still. Britten's ferocious scherzo is capped by a startling, intense account of the Passacaglia. Unmissable, and recorded in sensational sound too.

Debussy's keyboard output lends itself to many approaches. A touch of fallibility can be fine, as long as the musical intent is present – and players who over-accentuate the technical demands can sound flashy and superficial. Michael Lewin's technique is phenomenal, but he's too generous a player to draw attention to himself at Debussy's expense. Sample his dazzling, thunderous traversal of Feux d'artifice – it's delirious, giddy stuff, both entertaining and terrifying. The radical elements in Debussy's orchestral music are smoothed over by the lusher textures, whereas the piano music still sounds bold and modern. Lewin gives us the second set of Préludes, each one carefully characterised. Feuilles mortes has a deathly chill, in contrast to Bruyéres' delicate grace. Canope has an eerie stillness, and Les tierces alternées provides oblique light relief.

Good couplings too – Lewin opens the disc with a tender transcription of Debussy's early song Beau Soir, following it with a sparkling account of L'isle joyeuse. Rarer is Debussy's last solo piano piece, a bleak, sombre Élégie composed in 1915. Lewin's playing strips away the composer's customary colour to powerful effect. Three waltzes complete the disc. This is an imaginatively planned, idiomatically performed Debussy anthology, and an ideal entry point for anyone curious about this repertoire. Lewin's notes are a model of lucid accessibility, and Sono Luminus's sound is rich and immediate. Schumann: The Four Symphonies Berliner Philharmoniker/Sir Simon Rattle (Berliner Philharmoniker Recordings)

Schumann: The Four Symphonies Berliner Philharmoniker/Sir Simon Rattle (Berliner Philharmoniker Recordings)

This first release from the Berliners' own label is an impressive artefact: a handsome, clothbound hardback book. The CDs are accompanied by a Blu-ray audio disc, a passcode for downloading the music as high-resolution sound files, plus a week's access to the orchestra's Digital Concert Hall. None of which would matter a jot if the music-making was flat-footed. Happily, these are splendid Schumann performances, Sir Simon Rattle excelling in the very repertoire his detractors would accuse him of having little sympathy with. But I loved his EMI Brahms cycle, so I'm biased. This set is better still; the performances unmannered, affectionate and immaculately played. There's plenty of air and colour in the orchestral sound; Schumann's style is miles away from Brahmsian heaviness. When the music's in full flight, it's difficult not to grin. Sample the quicksilver strings at the start of no 2's finale, or the perky dotted first subject of Symphony no 1. And Rattle is well-attuned to Schumann's dreamy flipside; the sudden sidesteps into the shadows which occasionally suggest that not all is well.

There's an interesting sleeve note comment from Rattle on the Rhenish Symphony's solemn fourth movement – for him, a place where “the extrovert joviality is silenced... a glimpse into the unfathomable depths of a soul...” The dark brass sonorities are judged to perfection. It's awe-inspiring stuff, but I don't agree with Rattle's view of the symphony's finale as offering false hope. These players make it sound powerfully upbeat, and the coda's joy feels thoroughly deserved. I like Rattle's swift, unpompous tempo for the first movement too. He gives us no 4 in its leaner, earlier form. I've always liked the more familiar revision, but the 1841 original is clearly a very different beast – in the conductor's eyes, “a symphony of lightness and grace”, compared to the heavier, darker rewrite. It really takes flight here, and you're made aware of Schumann's originality in joining the four movements so neatly. The expansive, introspective 2nd Symphony emerges as the boldest, most forward-looking of the set. Why aren't these works performed more often? A life-affirming set, exquisitely presented. Bequeath it to a loved one in your will.

Add comment