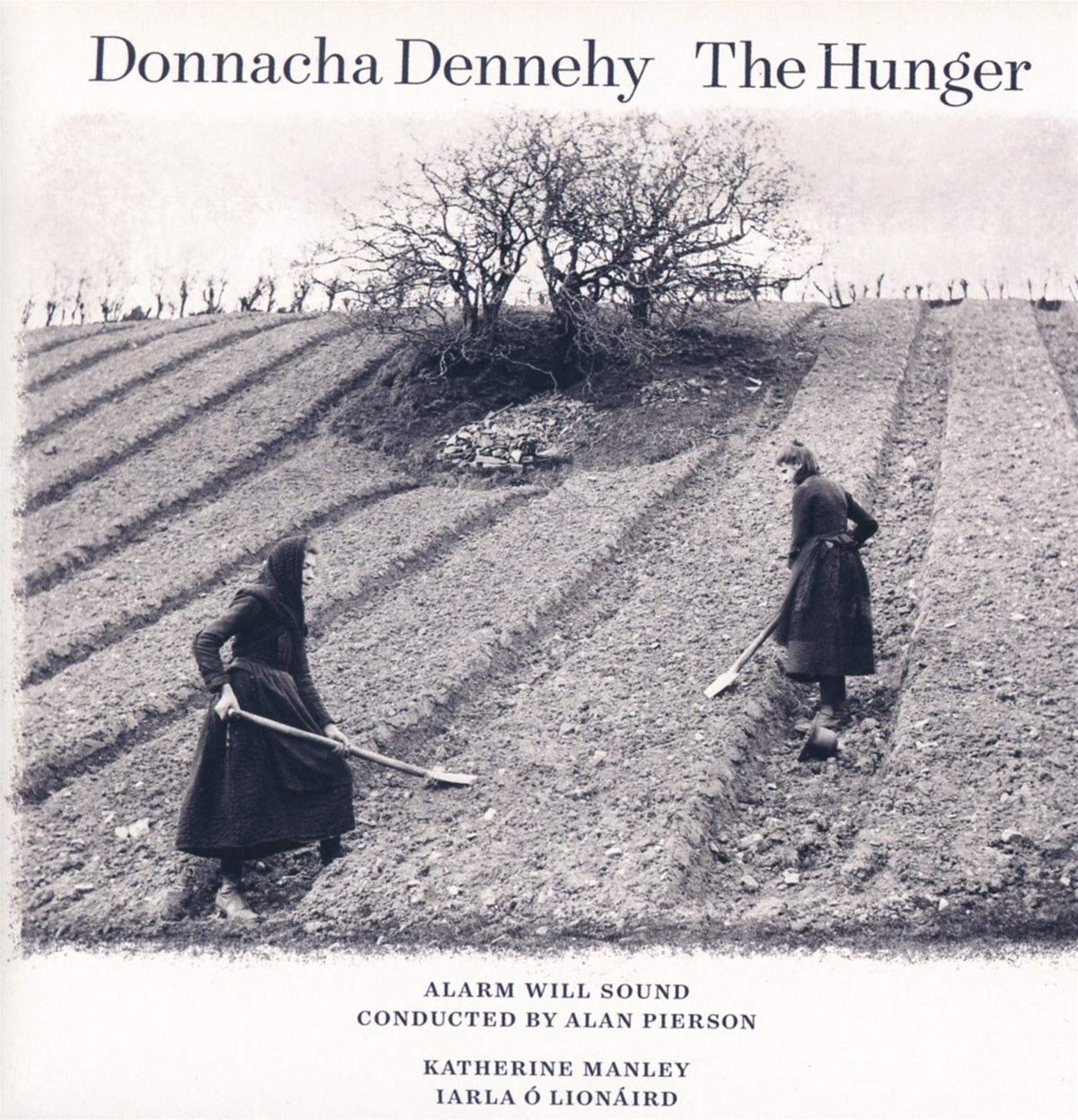

Donnacha Dennehy: The Hunger Alarm Will Sound/Alan Pierson, with Katherine Manley and Iarla Ó Lionáird (Nonesuch)

Donnacha Dennehy: The Hunger Alarm Will Sound/Alan Pierson, with Katherine Manley and Iarla Ó Lionáird (Nonesuch)

The Great Irish Famine of 1845-1852 resulted in the deaths of one million Irish citizens to starvation and prompted a further million to emigrate. In 1851, American social reformer Asenath Nicholson travelled across the Atlantic to document exactly what was happening, traversing the length of Ireland on foot. Nicholson’s text forms a substantial chunk of the libretto of Donnacha Dennehy’s The Hunger, extracts from her report interspersed with lyrics taken from the song Na Prátaí Dubha (“Black Potatoes”), the words written by one Máire Ní Dhroma from Wexford. The work is framed as a dialogue between Nicholson and a nameless elderly native.

It's a horrific tale, made more shocking by the realisation that exports of certain foods from Ireland actually increased during the famine, and Dennehy’s music is appropriately sombre. Nicholson hints at the cruel ineptitude of the British government; especially chilling are her descriptions of a ravaged landscape, her heart sickening “at looking over the utter wasting of all that was once cheerful, interesting and kind…” Soprano Katherine Manley takes the role of Nicholson is a sympathetic, pure-voiced observer, brilliantly partnered by vocalist Iarla Ó Lionáird as the anonymous old man. The fourth section’s lament for a dead child is devastating. Alan Pierson’s Alarm Will Sound tap into beauty and the suppressed anger of Dennehy's score.

Handel: Samson Dunedin Consort/John Butt (Linn)

Handel: Samson Dunedin Consort/John Butt (Linn)

Samson was premiered in Covent Garden in 1743, a hefty oratorio written by Handel in Dublin at the same time as Messiah, its libretto adapted from Milton’s Samson Agonistes. John Butt’s handsomely cast new recording makes a persuasive case for this big-boned, baggy work. Interestingly, the choruses exist in two versions here. On the CDs we get boys’ voices singing the soprano lines, though it's possible to download alternative takes featuring just Butt’s stellar cast of soloists, bolstered by a second alto. Both are effective, though I'm smitten with the sound made by the larger scale chorus, the boys’ voices (the excellent Tiffin Boys’ Choir) adding a thrilling edge to the fruitier moments. The most famous one comes near the close, soprano Mary Bevan’s “Let the Bright Seraphim” a treat, and blessed with some glorious natural trumpet playing.

Brisk speeds and agile accompaniments make this performance fly by. Joshua Ellicott’s Samson is an appealingly sympathetic character, delivering an eloquent “Total eclipse” in Act 1, Sophie Bevan's Dalila equally charismatic. There's fun alongside the drama too: sample the chorus of warring Israelites and Philistines which closes Act 2. Handsomely produced, with outstanding notes and glowing sound, this is a treat.

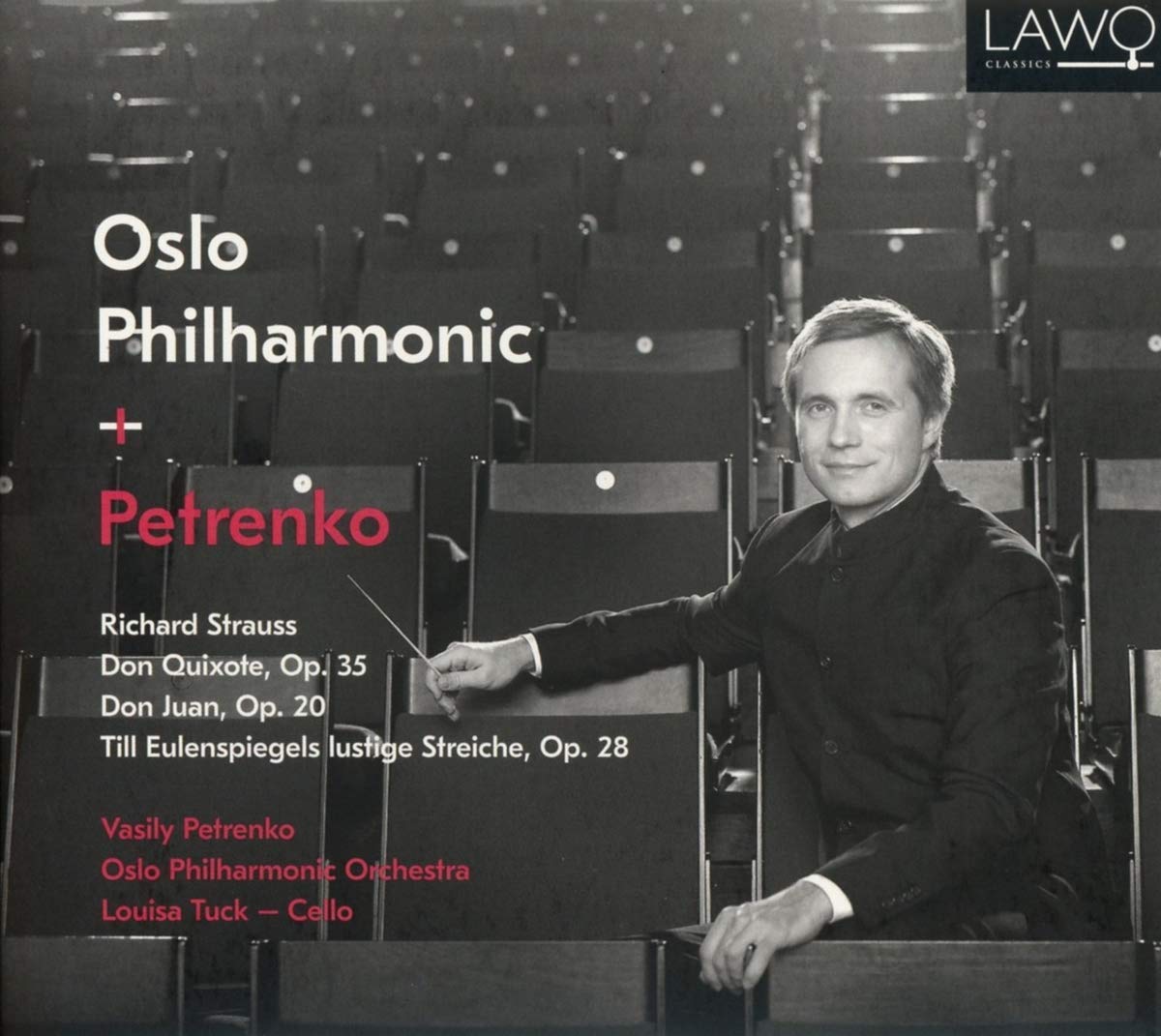

Strauss: Don Quixote, Don Juan, Till Eulenspiegel Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra/Vasily Petrenko (Lawo Classics)

Strauss: Don Quixote, Don Juan, Till Eulenspiegel Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra/Vasily Petrenko (Lawo Classics)

Don Juan and Till Eulenspiegel are concise marvels which set my pulse racing each time I hear them, but I'm now inclined to agree with a colleague: Strauss’s Don Quixote is the composer's deepest, most profound tone poem. Though extravagantly scored, there's no hint of bombast. And it's a structural marvel, Cervantes’ sprawling novel condensed into an elaborate orchestral work that's part double concerto, part variation sequence. Strauss’s gift for counterpoint reached a peak in the work’s extended introduction, a dazzling, playful overlaying of the three main themes. One of this performance’s joys is cellist Louisa Tuck – crucially not an imported celebrity soloist but the Oslo Philharmonic’s regular principal. Meaning that her exchanges invariably ring true; Quixote's bittersweet death is exquisite here, Vasily Petrenko capping it with the sweetest of codas. The orchestral playing is superb throughout: sheep, flying horses and windmills uncannily vivid. My new favourite Don Quixote, magnificently engineered.

Excellent couplings too: an impulsive, swaggering Don Juan, and a wonderfully nimble reading of Till. I'm still amazed at the sheer variety of incident packed into this work in barely 15 minutes; there's not a wasted note. Solo horn and clarinet are outstanding throughout, and notice how well Petrenko ramps up the tension when Till is sentenced just before the close. Though the actual ending isn't at all bleak, and it's difficult not to grin - Strauss's stated intention “to give people in the concert hall a good laugh for once,” borne out, handsomely so.

Add comment