Prokofiev: Symphonies 4 (Op.47) & 5, Dreams Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra/Kiril Karabits (Onyx)

Prokofiev: Symphonies 4 (Op.47) & 5, Dreams Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra/Kiril Karabits (Onyx)

Prokofiev was adept at recycling good ideas. His Symphony No. 3 is linked thematically to the opera The Fiery Angel, and the less abrasive No 4 shares some ideas with the ballet The Prodigal Son. The piece was radically revised in 1947 and became Prokofiev's Op 112, though I've always preferred the more compact earlier version. Composed in 1929, it's full of delectable ideas, the lyricism anticipating the scores written after his return to Russia in the mid-1930s. Like the beautiful woodwind chorale which opens the symphony, or the infectiously energetic theme which kicks off the movement's Allegro eroico. You can sense Prokofiev's symphonic technique developing; the transitions between themes are deftly handled and there are few longeurs. There's a beautiful Andante tranquillo and a charmer of a scherzo. Only the blustery finale slightly outstays its welcome, though you forgive it for a delicious final cadence which could only have come from Prokofiev's pen. Karabits' winds and brass excel, though the boomy recorded sound means there's a loss of detail.

Outstanding recordings of Prokofiev's Symphony No. 5 abound. This one is very decent, but Andrew Litton's recent Bergen CD is sharper and crisper; Karabits is smoother, downplaying the music's subversive edge. The slower, more self-consciously epic moments work best – the first movement's clangorous coda is superb, as is the Adagio's harrowing central climax. As a bonus we get the Op. 6 Dreams from 1910, a ripely-scored tone poem dedicated to Scriabin.

Smetana: String Quartets Pavel Haas Quartet (Supraphon)

Smetana: String Quartets Pavel Haas Quartet (Supraphon)

Bedrich Smetana’s severe deafness prevented him from enjoying the private first performance of his String Quartet No. 1, held in his secretary’s apartment with Dvořák playing the viola part. The quartet was written in 1876 after a move away from Prague; Smetana still hoped that his hearing loss was only temporary and composed this powerful, visceral work “for four instruments that, in a narrow circle of friends… talk about that which has moulded me.” Youthful energy and first love are suggested with startling accuracy. Smetana’s deafness is depicted with alarming realism: the pulsating last movement collapses into silence, followed by a shrill high E harmonic played by the first violin. It’s a thrilling, shocking coup de theatre, wonderfully realised here by the Pavel Haas Quartet. Smetana does give us a tender, consolatory coda, though the prevailing mood remains bleak. I’ve never heard such a sharply drawn performance. Sforzandi explode, and Smetana’s more upbeat ruminations are delightful. The second movement polka has irrestible bounce. A tender Largo sostenuto features some exquisite work from viola and cello. It grips, helped by Supraphon’s close, rich sound.

The Quartet No. 2 was also premiered privately, in 1883. Smetana’s diminishing self-confidence prompted him to write that “my musical ideas are slowly losing their vitality… everything is somewhat cloaked by a mist of despondency and grief.” He was mistaken; this taut, concise work is as striking as its predecessor. Barely 19 minutes long, it receives another startling reading. The first 20 seconds of the third movement alone are worth the disc price. You can smell the players’ sweat. Despite the angst, the mood is ultimately upbeat, and the quartet’s finale closes in a mood of defiant affirmation. Sensational performances of music which deserves to be far better known, and magnificently recorded.

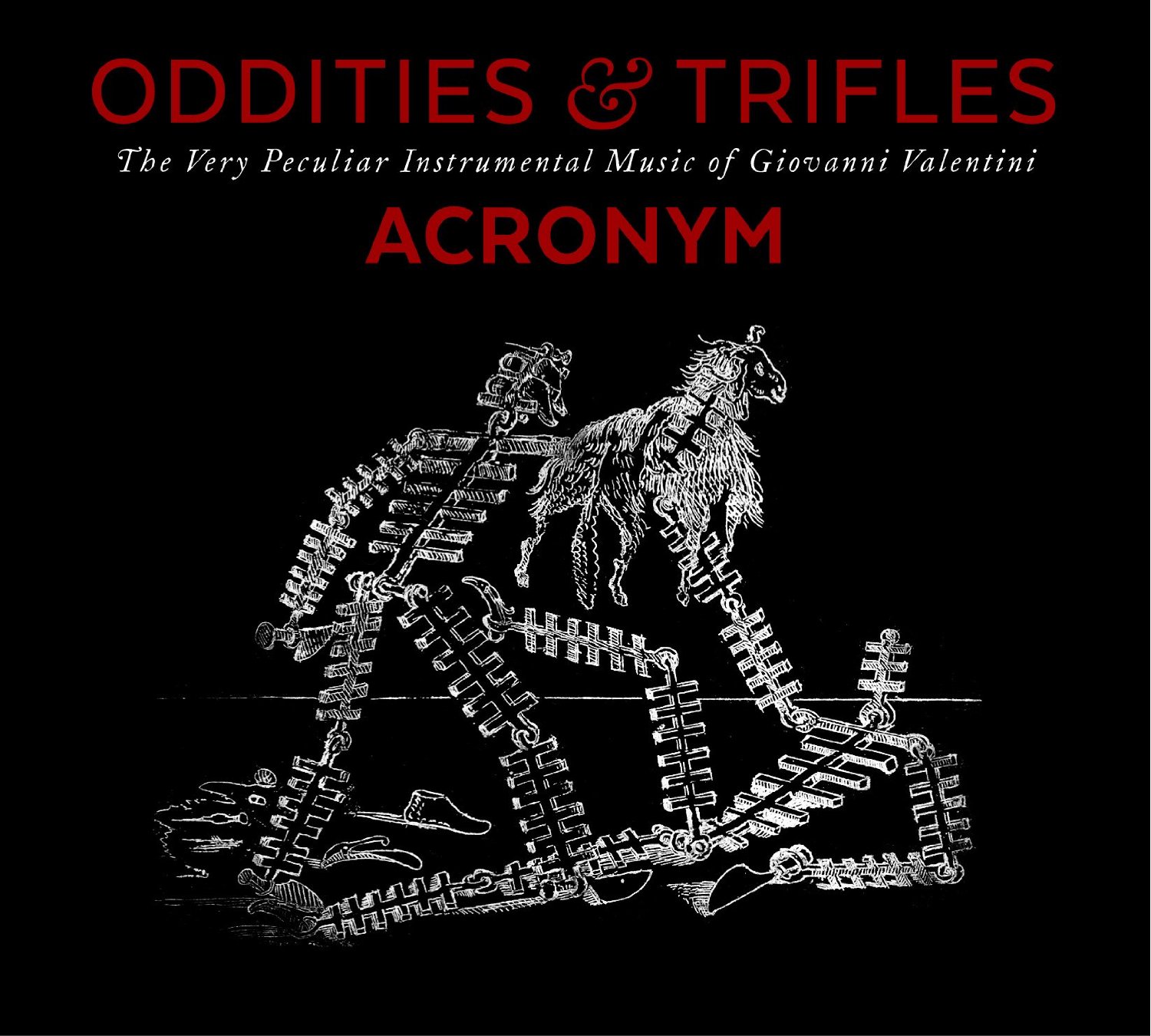

Oddities & Trifles: The Very Peculiar Instrumental Music of Giovanni Valentini ACRONYM (New Focus Recordings)

Oddities & Trifles: The Very Peculiar Instrumental Music of Giovanni Valentini ACRONYM (New Focus Recordings)

There are moments of such harmonic and rhythmic implausibility on this disc that it’s tempting to conclude that Giovanni Valentini’s music is a smart hoax. But no – he was definitely born in Venice in the late 16th century and may have been taught by Gabrieli. He was also a poet, and became Hofkapellmeister to the Viennese court in 1626, remaining influential in the city until his death in 1649. One of Valentini’s works has a notated part for water-filled clay bird whistles, and having access to enharmonic keyboard instruments (where Bb is not the same as A#) must have encouraged him to develop a freer approach to harmony.

The amount of legwork which must have gone into planning and researching this release is mindboggling. It would also be worthless if the music presented wasn’t up to scratch. Happily, it is, and this delightful release is one of the most striking things I’ve heard this year. The Sonata a5 which opens proceedings is a case in point: 45 seconds in, we’re simultaneously discombobulated and delighted by a chord progression which would still startle if it was written in the mid 20th century. Sample the descending chromatic melody which dominates the tiny Canzona a6. They’re all performed by the 12-piece string ensemble ACRONYM (you’ll have to read the booklet to find out what the letters stand for), negotiating Valentini’s tricky corners with ease. Violinist Beth Wenstrom is outstanding in a substantial solo sonata, and Elliot Figg’s dainty organ playing in a tiny Echo a3 is marvellous. The disc closes with a startling Sonata a4, full of strange sounds and containing, possibly, the first notated ppp in musical history. Fascinating, and fun - this is one of those discs that you’ll buy multiple copies of and thrust into the hands of friends and relatives.

Add comment