I was a strange child, I didn’t really fit in. I would twitch and distort my face into awkward shapes. I obsessively bit my fingers and knuckles till they bled. I collected leaflets and piled them high in neat stacks in the corner of my room. I was constantly bombarded with invasive thoughts that would leave me completely paralysed. Teachers would admonish me for ‘showing off’, people would stare, doctors would shrug.

It turns out I had Tourette’s Syndrome and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Finally learning what was "wrong" with me gave my strangeness context but didn’t stop me feeling like an outsider. Music became a way for me to escape. When I practiced or performed all of my symptoms would completely stop. I used music as a self-therapy and composition became an important creative outlet for me. It’s perhaps no surprise then that in my work as a composer I am often drawn to stories about outsiders; people who just don’t quite fit in, people who are misunderstood.

My first opera The Monstrous Child with librettist Francesca Simon based on her book of the same name, is about the ultimate outsider: the Norse goddess of the dead, Hel. The half-alive, half-dead daughter of Loki and sister to her monstrous brothers the snake Jörmungandr and the wolf Fenrir. She’s an angry, emo teenager with a sarcastic voice whose body is rotting from the waist down, banished to the underworld by the god Odin (pictured below by Stephen Cummiskey: a scene from the Royal Opera production).  Francesca and I have teamed up once again on a cantata for two singers and orchestra, The Faerie Bride, which has its first performance tonight at the Aldeburgh Festival. Written for Marta Fontanals-Simmons, Roderick Williams, and the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, it is inspired by the Welsh myth of Llyn y Fan Fach, a "lady of the lake" tale about a faerie who doesn’t fit in and refuses to conform. The piece begins at the lake, a liminal place where the human and faerie worlds meet.

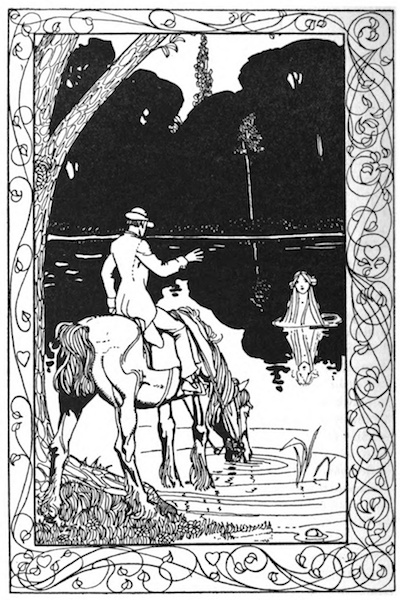

Francesca and I have teamed up once again on a cantata for two singers and orchestra, The Faerie Bride, which has its first performance tonight at the Aldeburgh Festival. Written for Marta Fontanals-Simmons, Roderick Williams, and the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, it is inspired by the Welsh myth of Llyn y Fan Fach, a "lady of the lake" tale about a faerie who doesn’t fit in and refuses to conform. The piece begins at the lake, a liminal place where the human and faerie worlds meet.

The Man sees The Woman sitting on the water and falls instantly in love. The Woman warns him "I am wild. It’s not easy to catch me", but agrees to marry him on one condition; that he does not strike her three times. If he does, she will return to the lake forever. He agrees — "not one blow, not ever" — but he has not listened carefully enough, he has misunderstood that not all blows are physical. She leaves the lake followed by a motley dowry of otherworldly cows, sheep, horses and pigs. They marry and move to the village, but she is too strange and doesn’t fit in. She runs barefoot, she swims naked, she waves at the moon, she talks to the cows, she sings strange songs.

At their neighbours' wedding The Woman, rather than dancing, sits quietly — she has faerie sight and can see an unhappy future for the couple. The Man questions her "faerie ways" and strikes the first heart-blow. At the christening of the neighbour’s child The Woman, rather than celebrating, cries and weeps — she has faerie sight and can see the child is not long for this world. The man chides her once more and strikes the second heart-blow. At the funeral of the child, rather than crying, The Woman laughs and sings – she has faerie sight and can see the child is in a better place now with the Tylwyth Teg (the Fair Folk). The Man is horrified and upbraids her, thus striking the third and final heart blow. She turns and walks back to the lake, calling her dowry to come home. The procession, including slaughtered pigs and cows that have "jumped down from the meat hook", follow her back into the watery depths, never to return.

At their neighbours' wedding The Woman, rather than dancing, sits quietly — she has faerie sight and can see an unhappy future for the couple. The Man questions her "faerie ways" and strikes the first heart-blow. At the christening of the neighbour’s child The Woman, rather than celebrating, cries and weeps — she has faerie sight and can see the child is not long for this world. The man chides her once more and strikes the second heart-blow. At the funeral of the child, rather than crying, The Woman laughs and sings – she has faerie sight and can see the child is in a better place now with the Tylwyth Teg (the Fair Folk). The Man is horrified and upbraids her, thus striking the third and final heart blow. She turns and walks back to the lake, calling her dowry to come home. The procession, including slaughtered pigs and cows that have "jumped down from the meat hook", follow her back into the watery depths, never to return.

The Welsh "lady of the lake" myth is just one of many "watery wife" tales from northern Europe that include the Mermaids of Ireland, the Kelpie of Scotland, and the Selkie of the Shetlands and Scandinavia (pictured below: Munch's Separation). However, in each of those the women are portrayed as either malevolent (pulling hapless men to their deaths), have something magical stolen from them which they plot to get back (seal skin, red cap, or silver bridle), or are captured by men and kept in human form. The faerie myths of Wales are unique in that the woman in each tale sets very clear conditions under which she agrees to marry the man (he shall not strike her three blows or hit her with clay), the breaking of which would result in her returning to the lake forever. The Welsh myths are empowering, with strong female characters who set their own agenda. There is no coercion, theft, or kidnap but rather misunderstandings and cultural differences.

The Faerie Bride is about compromise and respect in relationships, about understanding and accepting people as they are and not trying to change their nature. It’s about suspicion and fear of the outsider, and the societal pressures to conform in insular communities, something this faerie refuses to do.

But it’s also about the acceptance of death. At the end of the cantata The Women slips quietly back into the lake — "she was there, and then not there. Here, and then not here" — and ultimately The Man is left alone with his grief, hopelessly returning to the lake each day in the hope of catching a glimpse of her in the water, unable to let go.  As I write this my wonderful grandmother, Margaret, has just passed away. Growing up I always suspected there was something other-worldly about her. She was born not in a lake but in a forest. She would recite poems in a strange old language — Wully yudded varest zhip, thee ‘as more roits than oiy. Thoi c’ust wander where thy please, where’st oiy must walk on boiy. She would take handkerchiefs in her hands and dance around to brass band music. Like a leprechaun she could magic money from thin air. She was impish and mischievous and, like the faerie of our tale, she refused to conform; she was wild and impossible to catch.

As I write this my wonderful grandmother, Margaret, has just passed away. Growing up I always suspected there was something other-worldly about her. She was born not in a lake but in a forest. She would recite poems in a strange old language — Wully yudded varest zhip, thee ‘as more roits than oiy. Thoi c’ust wander where thy please, where’st oiy must walk on boiy. She would take handkerchiefs in her hands and dance around to brass band music. Like a leprechaun she could magic money from thin air. She was impish and mischievous and, like the faerie of our tale, she refused to conform; she was wild and impossible to catch.

She and my grandfather were together for nearly 70 years and in that time they never spent a single day apart. Her final days were full of love as he sat by her side stroking her face and combing her hair, trying to come to terms with the fact she would soon leave him forever. Despite her deterioration my granddad still believed she was a "strong woman" and might just pull through and get better. It was heart-breaking and desperately sad, but also the most beautiful thing; how many people can say they they’ve given a lifetime to someone? But coming to terms with that kind of loss is almost inconceivable. The passing of my strange and wondrous nan has made our world a little less colourful, but the stories we tell of her are recited in technicolor.

The cantata ends where it began, with The Man at the edge of the lake hoping to hear his faerie bride once more — "sometimes I think I hear her voice, as the wind whispers over the wate.". Like him, we will all eventually have to stand at that same lake between this world and the other and embrace the grief of losing those we love. But they can live on in the tales we tell and the music we sing.

- The Faerie Bride receives its world premiere at the Aldeburgh Festival tonight and will also be broadcast live on BBC Radio 3

- .Classical music reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment