theartsdesk at Bard Summerscape Festival 2019: unknown treasures and crosscurrents galore | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk at Bard Summerscape Festival 2019: unknown treasures and crosscurrents galore

theartsdesk at Bard Summerscape Festival 2019: unknown treasures and crosscurrents galore

'Korngold and His World' explores a heady confluence of old and new

There could be no greater gift to any festival director than Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Where the exploration of his life, times and contemporaries is concerned, this composer is a veritable Spaghetti Junction for different strands of genre, development and fates.

One of the most remarkable child prodigy composers in history, Korngold (pictured below in 1916, c AKG-Images/Bard) was the son of the Viennese music critic Julius Korngold. He studied with Zemlinsky (on Mahler’s advice) and enjoyed a meteoric rise to fame; his opera Die tote Stadt, premiered when he was 20, was a smash hit in the 1920s. Desperation to escape his father’s monstrous control-freakery also led him to work for some years in operetta. With the Nazis’ rise to power he was fortunate, being Jewish, to move to Hollywood; he later credited Warner Brothers with saving his life and those of his family.

He wrote relatively few film scores, but won two Oscars and was largely responsible for creating the sound that was long considered typical “film music” - the truth, of course, is not that Korngold sounds like film music, but that film music sounds like Korngold. In 1950, though, he attempted a comeback in Vienna, only to find that not only was his presence an unwelcome reminder of a shameful past era, but that his style was considered an anachronism. He died aged only 60 in Hollywood, believing himself forgotten. In the past few decades, changing times and evolving attitudes have allowed his distinctive voice with its emotional and melodic largesse to be fully appreciated on its own terms - often for the first time.

He wrote relatively few film scores, but won two Oscars and was largely responsible for creating the sound that was long considered typical “film music” - the truth, of course, is not that Korngold sounds like film music, but that film music sounds like Korngold. In 1950, though, he attempted a comeback in Vienna, only to find that not only was his presence an unwelcome reminder of a shameful past era, but that his style was considered an anachronism. He died aged only 60 in Hollywood, believing himself forgotten. In the past few decades, changing times and evolving attitudes have allowed his distinctive voice with its emotional and melodic largesse to be fully appreciated on its own terms - often for the first time.

Mix together the child prodigy years, the melting pot of influences; the splices of the serious and the "light": the fading 19th century and horrifying development of the 20th; and the worlds of Mahler’s Vienna, 1940s Hollywood and shattered post-war Europe. There’s enough material to keep any festival going for probably a year.

At Bard Summerscape, the co-artistic directors - the conductor Leon Botstein and the musicologist Christopher Gibbs - build the programme around a composer and his/her hinterland each year. The Bard College campus in upstate New York, close by the Hudson River and the Catskills, is blessed with an arts centre - to give it its full name, the Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts - designed by Frank Gehry (pictured below).  The one problem for a visiting Korngold fan from London is that because the festival is spread out over several intensive patches, I was only able to attend a few days of it. It had begun with the first-ever US staging of Korngold’s most ambitious and arguably greatest opera Das Wunder der Heliane - 92 years after its 1927 world premiere - and continued with two long weekends of concerts, talks and discussions. I arrived in time for the first weekend (I took part in the symposium on the child prodigy phenomenon), but not Heliane - however, I’m reliably informed that the run exceeded box office expectations and struck powerful resonances with its dystopian tale of spiritual and emotional resistance in a vicious totalitarian state. If Das Wunder der Heliane has become relevant, that says something terrifying about our own times.

The one problem for a visiting Korngold fan from London is that because the festival is spread out over several intensive patches, I was only able to attend a few days of it. It had begun with the first-ever US staging of Korngold’s most ambitious and arguably greatest opera Das Wunder der Heliane - 92 years after its 1927 world premiere - and continued with two long weekends of concerts, talks and discussions. I arrived in time for the first weekend (I took part in the symposium on the child prodigy phenomenon), but not Heliane - however, I’m reliably informed that the run exceeded box office expectations and struck powerful resonances with its dystopian tale of spiritual and emotional resistance in a vicious totalitarian state. If Das Wunder der Heliane has become relevant, that says something terrifying about our own times.

Friday evening began with an introduction from Botstein himself, a powerful articulation of some of the central arguments that surround Korngold: most of all, perhaps, the matter of how the arts should, can and do respond to heinous politics. The concert itself was dedicated entirely to Korngold music of many genres: some enchanting pieces from his ballet Der Schneemann, written when he was 11 and played with spirit by the pianist Anna Polonsky; extracts from the Op.9 Sechs einfache Lieder, early teenage works yet irresistibly melodic and sensitive, with the soprano Erica Petrocelli; and a lucid, streamlined account of the Piano Quintet of 1921 with luxury casting of the pianist Piers Lane and the Parker String Quartet (pictured below).

Then: off to the movies. The Overture from The Sea Hawk, the Cello Concerto Op. 37 (first created for the Bette Davis film Deception) and the short cantata Tomorrow (from The Constant Nymph) were each preceded by the appropriate Warner Brothers trailer. Hearing music from three scores side by side also provided a chance to appreciate how very different they are and how thoroughly Korngold could capture the essences of a drama, whatever its nature. Soloist Nicholas Canellakis flew through the Cello Concerto (pictured below) with immense fire and lyricism; Stephanie Blythe’s megawatt mezzo-soprano lifted Tomorrow to whole new levels of heartrending (pictured further below).

"The Orchestral Imagination" programme, with the American Symphony Orchestra under Botstein, made a promising start, having assembled an intriguing selection of works by Julius Bittner, Franz Schreker, Korngold and Zemlinsky’s Lyric Symphony. The Bittner story is worth telling: a close friend of Korngold’s, the composer suffered from diabetes and eventually both his legs were amputated. Korngold – who deserves an extra accolade as one of the best human beings in musical history – made over some of the royalties from his Strauss-based operetta Walzer aus Wien to him by way of support. The work, happily, was reinvented in the US as The Great Waltz.

Bittner’s Prelude to Der Musikant was lively and affectionate, and Schreker’s settings of Walt Whitman in translation, Von ewigen Leben, was superbly sung by Petrocelli amid orchestration that glimmers and glows like an aural Klimt. Unfortunately, though, the Korngold Piano Concerto for the left hand was the sort of car-crash that must be any festival’s worst nightmare. Pianist Orion Weiss was an heroic soloist, but his plane had been cancelled and he had arrived in time only for a fraction of the planned rehearsal. Maybe the orchestra had looked at the piece, but it did not sound like it.

The afternoon offered "Korngold and fellow conservatives" of the pre-war years - among them Schmidt, Braunfels, Dohnányi, Schoek and Josef Labor, whose Quintet for clarinet, piano and strings was a special treat: its almost disingenuous charm was delivered with all the necessary space and light by pianist Danny Driver, Antunes and Canellakis with violinist Aaron Boyd and violist Marka Gustavsson. Korngold’s ambitious Suite for left-hand piano and string trio was a fitting climax for the afternoon - but I can’t help wondering if it is wholly accurate to describe Korngold as a "conservative". It’s true that he did not write 12-tone music - but as a child prodigy, his music shocked his father, teacher and peers with what some described as its “dubious modernity”. It was far too radical for their tastes.

And so to operetta - a programme cleverly themed around the view of America presented in Viennese works of the time, notably Rosen aus Florida (started by Leo Fall and completed by Korngold) and Kálmán’s Die Herzogin von Chicago - namely, “America? Get rich quick!” The second half was devoted to just the prologue from the Kálmán: an inspired choice that articulated the era’s changing musical tastes, pulling in everything from The Blue Danube to burgeoning enthusiasm (and sometimes hatred) for the saxophone, plus a foxtrot based on Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, all of it culminating in the triumph of…the good old Hungarian czárdas. Korngold’s tenure at the Theater an der Wien, arranging and conducting operetta, sometimes in collaboration with the stage director Max Reinhardt, must have been not only a good source of financial independence, but also a heck of a lot of fun.

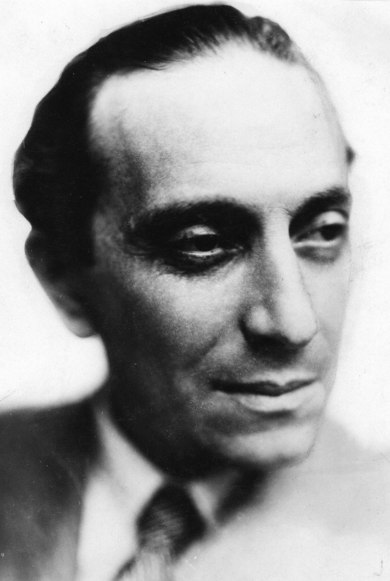

Proof, too, that music of this ever-underrated genre can be as inspired and memorable as anything ‘serious’ – sometimes more so. In Paul Abraham's exquisitely beautiful tenor song "Reich mir zum AbschiedW (from Viktoria un ihr Husar of 1930) we sense, with hindsight, a goodnight to a vanishing Europe that was soon destroyed in the conflagration of World War 2. A highly successful operetta composer, the Hungarian Jewish Abraham (pictured right in 1931) escaped to Cuba and then the US, but in 1946 experienced a devastating breakdown, attempting to conduct an invisible orchestra amid the ferocious traffic of Madison Avenue, New York. He spent the rest of his life in mental hospitals, including a spell in Germany being treated by an ex-Nazi. Now at last some of his jazz-age operettas are being revived by Barrie Kosky at the Komische Oper, Berlin, where we hear audiences can’t get enough of the likes of Roxy und ihr Wunderteam– in which an English bride runs away with the Hungarian national football team.

Proof, too, that music of this ever-underrated genre can be as inspired and memorable as anything ‘serious’ – sometimes more so. In Paul Abraham's exquisitely beautiful tenor song "Reich mir zum AbschiedW (from Viktoria un ihr Husar of 1930) we sense, with hindsight, a goodnight to a vanishing Europe that was soon destroyed in the conflagration of World War 2. A highly successful operetta composer, the Hungarian Jewish Abraham (pictured right in 1931) escaped to Cuba and then the US, but in 1946 experienced a devastating breakdown, attempting to conduct an invisible orchestra amid the ferocious traffic of Madison Avenue, New York. He spent the rest of his life in mental hospitals, including a spell in Germany being treated by an ex-Nazi. Now at last some of his jazz-age operettas are being revived by Barrie Kosky at the Komische Oper, Berlin, where we hear audiences can’t get enough of the likes of Roxy und ihr Wunderteam– in which an English bride runs away with the Hungarian national football team.

Bard Summerscape ends this weekend with music celebrating the emigré composers of Hollywood, "Art after the Catastrophe" with Hindemith, Strauss and Korngold’s Symphony in F sharp, and a concert performance of Die tote Stadt. The distance of time is finally allowing music that was suppressed for every reason other than its inherent nature to have its belated day in the sun

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Hallé John Adams festival, Bridgewater Hall / RNCM, Manchester review - standing ovations for today's music

From 1980 to 2025 with the West Coast’s pied piper and his eager following

Hallé John Adams festival, Bridgewater Hall / RNCM, Manchester review - standing ovations for today's music

From 1980 to 2025 with the West Coast’s pied piper and his eager following

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James's Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James's Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Add comment