Oslo is a winter wonderland, and adults seem to be outnumbered by children, flocking from all over Norway to Disney on Ice. It’s the deep snow and the silence in pockets of the city rather than the kids which make me wonder if anyone has set Handel’s Alcina in the icy lair of C S Lewis’s White Witch, with hero Ruggiero as Edmund fed Turkish delight from the magic phial. There's even a captive lion. Francesco Negrin’s straightforwardly magical production - look, no metatext! - at the sparkling newish Oslo Opera House does a fine job conjuring a snow-free magic island full of adult sexual shenanigans and the singing ranges from average to inspired. But I’m here to focus my attention on the pit, where violinist Bjarte Eike and harpsichordist Christopher Bucknall are joint-directing Eike’s Barokksolistene.

Why, you might wonder, when we have plenty of fine baroque bands visiting and based in the UK; might I not just be out for a jolly jaunt? Well, it’s true that I’ve wanted to visit the award-winning Opera House on the harbour since it opened in 2008. But I’ve just been captivated by a disc in a thousand, Eike’s The Image of Melancholy, one of those genuinely thoughtful programmes where Dowland, Holborne, Byrd and Eike’s exquisite playing of a Biber sonata movement somehow mesh with bittersweet Norwegian wedding marches and Celtic moods (if you don’t believe my enthusiasm, read Graham Rickson’s review).

When I meet Eike for a coffee in the stunning foyer of the breathtaking opera house (pictured right) – Olafur Eliasson’s ice-crystal panels offsetting the infinite oak of the “Wave Wall” leading into the auditorium – he adds to what he’s so eloquently written in the CD booklet. Not only is the disc dedicated to his father; the first copy arrived only five minutes before he received the phone call about Eike senior's death. When I wax lyrical especially about the last track, Niel Gow’s Lament, which strikes me as more of a vibrant apotheosis after the grief-quotient in the programme - and as Graham points out, this is not an all-sombre disc - Eike enthuses: “It’s my favourite piece ever”. And he tells me that it was his father’s too; at their last meeting the funeral plans were broached. “He wanted that Niel Gow piece, and the rest of it was up to me.

When I meet Eike for a coffee in the stunning foyer of the breathtaking opera house (pictured right) – Olafur Eliasson’s ice-crystal panels offsetting the infinite oak of the “Wave Wall” leading into the auditorium – he adds to what he’s so eloquently written in the CD booklet. Not only is the disc dedicated to his father; the first copy arrived only five minutes before he received the phone call about Eike senior's death. When I wax lyrical especially about the last track, Niel Gow’s Lament, which strikes me as more of a vibrant apotheosis after the grief-quotient in the programme - and as Graham points out, this is not an all-sombre disc - Eike enthuses: “It’s my favourite piece ever”. And he tells me that it was his father’s too; at their last meeting the funeral plans were broached. “He wanted that Niel Gow piece, and the rest of it was up to me.

“I had a week to organise the funeral and I thought, I can’t play alone, so I wrote to a lot of musicians around Europe who knew my father, who’d made friends with them all, asking if they’d come, and they said yes. So they came to this little town in Norway and I had people from London, Copenhagen, Malmö, Oslo, north Norway, they sang and played, and I arranged it with the minister. I made the links, even did improvisations on the psalms and went into some melancholic piece afterwards. Then the wake was completely different, he was a very humorous guy, so we played a lot of music, told a lot of stories, people were laughing, all in his spirit, so it was a good ending”.

Eike is rightly proud of the disc, which he produced in collaboration with Barokksolistene's experienced guide and recording master Malcolm Bruno. He thinks it’s important to make not just a document but something truly personal. He’d noted the melancholic tone in the Scandinavian folk tradition, finding the same physical impulse in Holborne and Dowland, and compiled a list of beloved numbers over years. The emphasis on reflection is also unusual, but Eike thinks it's the Zeitgeist. "There are streams of melancholy in our society and people are tired that everything’s going so fast. You can see it in pop music in Scandinavia, it’s back to the singer songwriter making simple things, it’s not so pumped up any more. In that sense I’m just part of my own time.”

Eike is rightly proud of the disc, which he produced in collaboration with Barokksolistene's experienced guide and recording master Malcolm Bruno. He thinks it’s important to make not just a document but something truly personal. He’d noted the melancholic tone in the Scandinavian folk tradition, finding the same physical impulse in Holborne and Dowland, and compiled a list of beloved numbers over years. The emphasis on reflection is also unusual, but Eike thinks it's the Zeitgeist. "There are streams of melancholy in our society and people are tired that everything’s going so fast. You can see it in pop music in Scandinavia, it’s back to the singer songwriter making simple things, it’s not so pumped up any more. In that sense I’m just part of my own time.”

The sound on the CD, as Graham has also remarked, is layered and beautiful. I was surprised, on my first evening at a “Baroque Extravaganza” concert in the Opera House the night before the Alcina, how the tone quality of the players came across as no less ravishing. “We’ve developed a way of playing which has a lot to do with really going in to the strings and capturing overtones, it’s really deep playing. This is the only way I can describe it, slow bowing and hardly ever the usual fast superficial stroke. We've worked hard to get this special contact so that you can really hear the wood and guts and grain."

As a self-confessed networker “before the term was even invented”, Eike has got to know musicians on his travels with whom he felt especially in sympathy, so he’s been able to handpick. “It removes a lot of frustration and you save time in rehearsals, especially for the sort of concert like last night’s which we had to throw together, if people are wanting the same thing. I don’t need to use my elbows.”

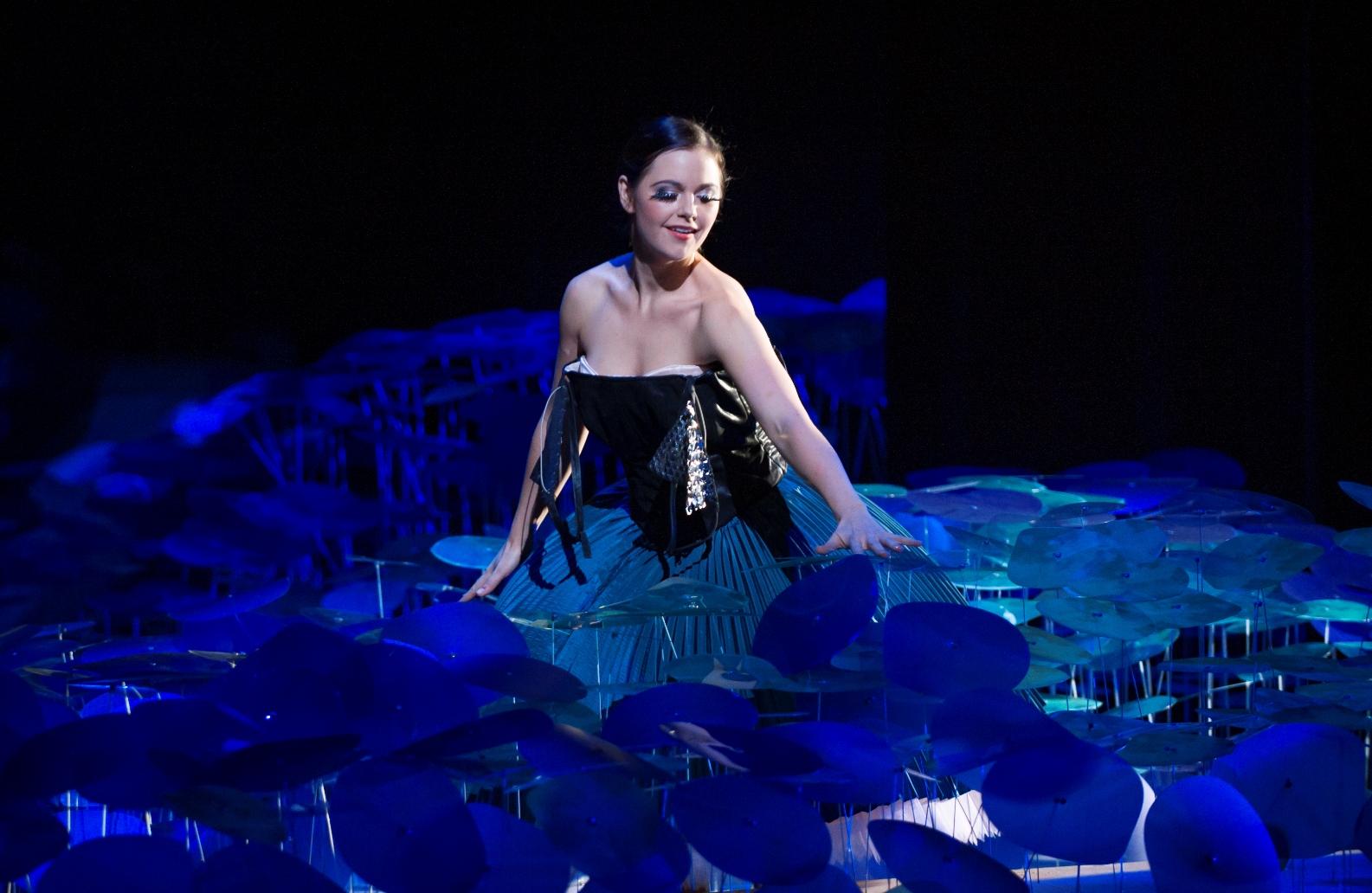

There’s also a refreshing honesty about the relatively simple needs of Handel. The Barokksolistene’s slogan has always been “it’s just old pop music”, the logo of the team’s first disc, London Calling, with mezzo Tuva Semmingsen (pictured right as Ruggiero with Nicole Heaston as Alcina - all production images by Jörg Wiesner). Eike holds to that: “in Handel especially, the structure is so basic – you need a groovy bass line which is walking, it has to be steady, and swinging”; I’ve already complemented him on the rocking double basses, the equivalent of the two wonderful Italians in the Göttingen Festival Orchestra I first heard in 2010. “Then you have these beautiful melodies, you have some interesting middle parts but it’s not like Bach, it’s not complicated, it is pop music. And if you lose the rhythmic element, there is nothing left for me in Handel. I don’t think you should lose it in Verdi either, but that's a whole different story”.

There’s also a refreshing honesty about the relatively simple needs of Handel. The Barokksolistene’s slogan has always been “it’s just old pop music”, the logo of the team’s first disc, London Calling, with mezzo Tuva Semmingsen (pictured right as Ruggiero with Nicole Heaston as Alcina - all production images by Jörg Wiesner). Eike holds to that: “in Handel especially, the structure is so basic – you need a groovy bass line which is walking, it has to be steady, and swinging”; I’ve already complemented him on the rocking double basses, the equivalent of the two wonderful Italians in the Göttingen Festival Orchestra I first heard in 2010. “Then you have these beautiful melodies, you have some interesting middle parts but it’s not like Bach, it’s not complicated, it is pop music. And if you lose the rhythmic element, there is nothing left for me in Handel. I don’t think you should lose it in Verdi either, but that's a whole different story”.

He talks about the clarion tenor singing Oronte in Alcina, Marius Roth Christensen, who has one of the most bewitchingly staged scenes in the opera, a real love sequence in Act Three with Silvia Moi’s shapely Morgana (pictured left). “He’s one of several in the cast who’d not sung baroque music before. He was quite worried early on, asking for help with tempi. He plays in one of the most successful underground cult bands in Norway. I told him, 'you just have to remember the timing when you play guitar and sing. Straight on the beat, not waiting for any impulse – you give it.' "

He talks about the clarion tenor singing Oronte in Alcina, Marius Roth Christensen, who has one of the most bewitchingly staged scenes in the opera, a real love sequence in Act Three with Silvia Moi’s shapely Morgana (pictured left). “He’s one of several in the cast who’d not sung baroque music before. He was quite worried early on, asking for help with tempi. He plays in one of the most successful underground cult bands in Norway. I told him, 'you just have to remember the timing when you play guitar and sing. Straight on the beat, not waiting for any impulse – you give it.' "

What’s so impressive about the Alcina, when I see it some time into the run that evening, is the incredibly close co-ordination between the singers and Eike’s band (Barokksolistene pictured below by Tatjana Dachsel). It comes from the sort of Utopian results that only usually happen in a place like Glyndebourne, where Vladimir Jurowski would be present from the first rehearsal (and surely his successor Robin Ticciati will be the same). “In discussing how it would work, I told Per Boye [Hansen, the National Opera boss] that it was important we keep the musical directorship with me because that is the sound, and it would be too frustrating to have some conductor coming in at the end. Otherwise just find a so called baroque expert and work with your own orchestra. I was quite clear and he was prepared to take the risk.

"Then Chris [Bucknall, harpsichordist and co-conductor] and I came and we only had two and a half weeks of stage rehearsals, very little; we were interrupted by the Christmas break. But we’ve been working with the singers from day one with harpsichord and violin, and I asked for another repetiteur, our second harpsichordist, then we brought the continuo people in. Because it’s not us doing the music and the director doing the production separately. Francisco’s working on the drama, we gather round the harpsichord, maybe we have to adapt some of our musical ideas to his stage ones and vice versa. We only decided on the cadenzas, for instance, after we saw what kind of characters he was looking for and what singers we had.”

"Then Chris [Bucknall, harpsichordist and co-conductor] and I came and we only had two and a half weeks of stage rehearsals, very little; we were interrupted by the Christmas break. But we’ve been working with the singers from day one with harpsichord and violin, and I asked for another repetiteur, our second harpsichordist, then we brought the continuo people in. Because it’s not us doing the music and the director doing the production separately. Francisco’s working on the drama, we gather round the harpsichord, maybe we have to adapt some of our musical ideas to his stage ones and vice versa. We only decided on the cadenzas, for instance, after we saw what kind of characters he was looking for and what singers we had.”

And it’s telling in performance. Maybe there’s less purely show-offishness than you might expect in Handel: that has happened in the gala with flashy countertenor David Hansen, whose top notes send a much noisier audience whooping with delight, no doubt as those of Farinelli used to. Not to my taste at all, and he didn’t exactly “own” his sparkly jacket, bobbing around like a puppet whose strings have been cut like Bostridge used to; but I’ve never witnessed this level of audience participation at home. The highlights of the “gala” for me were the incredible metrical changes and buffets of a superbly-executed Rebel dance suite, for all the world like Stravinsky’s Pulcinella before its time, and baritone Johannes Weisser taking over a Bartoli favourite, “Gelido in ogni vena” from Vivaldi’s Farnace.

No doubt about the high point of this Alcina, either: American soprano Nicole Heaston’s “Ah mio cor”, a lacerating display of fine-tuned star quality (Heaston pictured left). But its impact would have been so much less without the perfect musical-dramatic flow of everything in Act Two which led up to it, including the arias executed with dramatic vividness by Semmingsen’s Ruggiero - looking weirdly like the fabulous Vod in Fresh Meat, hope they see that in Norway - and Kristina Hammarström’s Bradamante. And always there was the orchestra to remind us of Handel’s little scraps of genius. I’ve never heard more exciting crescendi in this music; and Eike’s solos were, as expected, ravishing.

No doubt about the high point of this Alcina, either: American soprano Nicole Heaston’s “Ah mio cor”, a lacerating display of fine-tuned star quality (Heaston pictured left). But its impact would have been so much less without the perfect musical-dramatic flow of everything in Act Two which led up to it, including the arias executed with dramatic vividness by Semmingsen’s Ruggiero - looking weirdly like the fabulous Vod in Fresh Meat, hope they see that in Norway - and Kristina Hammarström’s Bradamante. And always there was the orchestra to remind us of Handel’s little scraps of genius. I’ve never heard more exciting crescendi in this music; and Eike’s solos were, as expected, ravishing.

Was the Opera House too big a venue? I can’t really judge as I was so close to the stage. But Louis Désiré’s fantasy designs certainly brightened the austere auditorium, with its ammonia-stained oak in such dark contrast to the gold-brown strain outside and that icy, compelling chandelier of 5800 hand-cut crystals you can see in the lead photo, designed by the architectural company Snøhetta responsible for the whole building (pictured below).

There were exoticisms in the foyer you might not see elsewhere, like operagoers arriving to park their skis in the open cloakroom, or a group proudly dressed in Sami traditional costume. I’d have liked to have been here to see all the spaces used as they were in the baroque-inspired ballet quadruple bill which Eike collaborated on last November. And an "alehouse" event in which he meets up with jazz and folk pals and improvises sounds like a must. We’ll enjoy something of the sort at the Spitalfields Festival this summer, by which time the whole of our conversation deserves to make an appearance as an Arts Desk Q&A.

There were exoticisms in the foyer you might not see elsewhere, like operagoers arriving to park their skis in the open cloakroom, or a group proudly dressed in Sami traditional costume. I’d have liked to have been here to see all the spaces used as they were in the baroque-inspired ballet quadruple bill which Eike collaborated on last November. And an "alehouse" event in which he meets up with jazz and folk pals and improvises sounds like a must. We’ll enjoy something of the sort at the Spitalfields Festival this summer, by which time the whole of our conversation deserves to make an appearance as an Arts Desk Q&A.

There was so much else in snowy Oslo to explore in limited time: the Akershus Fortress in deep snow, the 1930s murals of the amazing City Hall, the avenues and parks leading up to the Royal Palace, the Munchs and Novgorod icons of the National Gallery which, like the Munch House collection, will be moving to sleek new venues in due course. We didn't even get to the peninsula boasting a whole raft of museums or (top of my list but impractical given on-the-hour timings) the guided tour round Ibsen's apartment.Still, there was always his statue, larger than life, outside the National Theatre.

The abiding impression, though, was of the Norwegians' easy going respectfulness and openness , which is not quite what you might anticipate. But then the extrovert brilliance of the Barokksolistene is as good a clue as any as to what expectations might be confounded when you come to Oslo. It’s a different city in the spring and summer, I’m told, but our winter taste could hardly have been more beguiling. The White Witch’s domain with its many delights is fine by me.

Add comment