Keggie Carew: Beastly review - the history of animals and us | reviews, news & interviews

Keggie Carew: Beastly review - the history of animals and us

Keggie Carew: Beastly review - the history of animals and us

Are we more beastly than the beasts?

There’s been an avalanche of books about animals and trees. The more species disappear and forests are felled, the more titles are published: laments, celebrations, extinction alarms and rhapsodic accounts of animal sentience. Beastly is all of these rolled into one.

Keggie Carew’s book comes from a place many of us will identify with: a malaise about the present and the future, a sense of loss and grief. There’s a sense of disorientation, fuelled by the growing heat of climate change: what is our relationship with nature? Are we part of it or not? Are we animals or something else? Are we facing human extinction as well as the collapse of natural systems that have sustained us? The kids known as "furries”, who daily dress up as animals in US high schools, are a strange and yet fitting manifestation of this collective unease. I recently heard of a Californian teenager who wanted to change high schools: there were far too many ‘furries’ in hers, and some of the human “cats” had demanded the provision of litter trays in the lavatories.

Although the ‘furries’ don’t appear in Beastly, it’s just the sort of story that Keggie Carew might have included in her vast and wide-reaching compendium of real-life tales (as well as illuminating fictions) that describe our complex relationship with animals of all kinds: from horrific accounts of factory pig-farming, the luckless creatures totally immobilised in the cause of capitalist profit, to the loving rescue of big cats and the re-population of forests depleted by excessive hunting; from the mindless over-fishing of the oceans to the latest and promising attempts at rewilding.

Keggie Carew (pictured above) and her husband Jonathan are far from being just talk: they are themselves rewilding a patch of land in the English West Country. They really do care. Beastly is written with great passion. The author shares her sense of wonder as well as her fury. A recurring and telling element in her story is the work of Simona Kossak, a profoundly engaged zoologist who lives in the depths of Poland’s ancient Bialowieža Forest, and communes with the raven Korasek and the wild boar Zabka. There are some touching photographs, sadly not as well reproduced as they might be – for reasons of cost no doubt. This is a forest that has been a hunting ground for centuries, for Hermann Goering in Nazi times and communist party officials later.

Hunting is one of the subjects that Carew addresses, very vividly indeed – going back to the apparent respect that paleolithic peoples held for animals and their spirits, the subject of the powerful cave paintings we know so well, and aghast at the way in which today’s hunters speak of caring for the animals they kill. This is a fiendishly complicated subject, and not one that’s easily reducible to clearly defined right and wrong. To be fair, Carew doesn’t condemn all hunting, and admits to eating the ‘right kind of meat’. It isn’t possible – for me at least – to think about hunting without reference to Greek and Roman myth, in which Artemis and Diana are goddesses of the hunt as well as the ones who protect animals and look after their young. A paradox, but one which speaks profoundly about the human condition, not just in ancient times but throughout history and across cultures.

The origins of the myth of Artemis the huntress reach back to the matriarchal traditions – described with reference to “Old Europe” (Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans) by the Lithuanian archaeologist and anthropologist Marija Gimbutas. She finds the Great Goddess widely represented across this area of agrarian settlement, in the millennia that preceded the invasions of warror Aryans who brought male gods with them. The Goddess was Lady of the Beasts, who drew her power from an association with the animal world and its spirits, in a respectful system of belief and rituals that was more balanced than what followed with patriarchy. Carew doesn’t choose to allude to this, but there is a whole strand of eco-feminism, from the 1970s on that connected the already visible eco-catastrophe with not just capitalism but patriarchy. It’s now commonly accepted that the idea of humanity needing to conquer, control and exploit nature is rooted in Judeo-Christian monotheism. One God, male, wieding thunderbolts. Nature untamed, and needing to be subdued.

Carew is keenly aware of many of the paradoxes that unsetle us when we look into our relationship with animals and nature: the naturalist Wallace, for instance, a contemporary of Darwin, couldn’t help himself from killing immense numbers of specimens, not least butterflies, in a frenzy of collecting. Simultaneously, as the author points out, Wallace was in total awe before those creatures in full life, rather than lined up dead in glass cabinets. We find something of the same paradox in the ambiguous (or some would say hypocritical) discourse of the hunters we vilify, or reflected in the imagination of the Ancients those goddesses who were at once cruel and kind.

Keggie Carew is a great story-teller, and, along with the recurring anger, Beastly is a cornucopia of revealing tales – the multiplicity of which can feel at time disorientating. There’s plenty of startling material in her book, from the extinct sea-cows of Greenland to the startling fact that the ideas at the heart of Darwin’s theory of evolution were anticipated by a 9th century Baghdad polymath, Al-Jahiz. Carew has chosen a structure that sometimes feel like collage, with some very short sections, followed by longer ones, jokey chapter and paragraph titles that often refer to popular culture, movies TV and songs (the distinguished, if a little eccentric, entomologist Miriam Rothschild introduced as “Flea Girl”, the recurring title “Love, Actually). There are times when the omnipresnece of facile puns feels as if the author were relying - perhaps unnecessarily - on the need for light relief and a little silliness, in the face of harsh realities.

There’s a conundrum at the heart of the book – reflected in the punning title: Beastly could just refer to that which appertains to animals –the word’s original meaning. Or “beastly” in the sense of acting with unkindness. What is the contrast between our cherishing pets, recognising that they are able to help heal us, and having them brutally killed in factories so we can produce cheap food? In French, the language of super-rationalist Descartes, bête (the translation of ‘beastly’) means plain stupid, like an animal. Worth thinking about.

There’s a conundrum at the heart of the book – reflected in the punning title: Beastly could just refer to that which appertains to animals –the word’s original meaning. Or “beastly” in the sense of acting with unkindness. What is the contrast between our cherishing pets, recognising that they are able to help heal us, and having them brutally killed in factories so we can produce cheap food? In French, the language of super-rationalist Descartes, bête (the translation of ‘beastly’) means plain stupid, like an animal. Worth thinking about.

Just how sentient or ‘intelligent’ animals are, Carew will wisely not state: we’re not, she says, in a position to know. Even if we follow in the footsteps of Charles Foster, author of Being a Beast (2016) and try to live as badgers or other wild animals, we can only guess at what they feel. Quite rightly, Carew is very sceptical about current (and past) attempts to decode animal languages, from whale to bird-song. All too often, we impose an anthropomorphic perspective, ignoring the possibility that animal sentience and communication may not be decipherable in terms that we readily understand. That may indeed be where the riches lie – in a radically different kind of consciousness and ‘intelligence”. A friend of mine, actively involved in research into human-animal communication recently told me that academics in the field mostly admit that there’s something going on, beyond science’s present anthropocentric paradigm. To admit that animals might have something akin to ESP, though, would threaten their academic status.

Carew is astonished that “the cleverest creature that has ever breathed” should have such a mess of the planet, revealing as she writes, a still widely held view that our scientific knowledge and technical know-how are superior to that whatever ‘intelligence’ is possessed by animals. She lists over-population, along with pollution, habitat, invasive species, as factors that has led to the mass extinction of species. And yet it’s our cherished medicine’s impact on health and human lifespan that has in part caused such an exponential population explosion. Would Carew, I wonder, accept that nature alone should regulate the imbalances that threaten humanity’s future? This would mean accepting that we stop seeking to lengthen human life. Might that not be too ‘beastly’?

While “Beastly” describes some of the horrors inflicted on animals (pictured above) – on a massive scale, in the industrial era – she does not tackle humanity’s abiding propensity for violence and murder towards fellow humans. Our perverse taste for torture, which seems to come with the package of being human, and has never abated, is cause for reflection, and perhaps relevant to the ways in which we treat animals. We may no longer execute criminals so much in the ‘advanced’ West, but what should we make, in the grander scheme of things, of the appalling and sadistic treatment of the prisoners in Guantanamo and elsewhere – in this case by one of the so-called most advanced nations of the world.

The book wends its way towards something of a conclusion: we must, Carew suggests, recognise nature’s capacity for self-regulation. Though, here too, there are no easy answers. Darwinian ‘survival of the fittest’, an ideology that reflected the passion for competition which fuelled the great capitalist leap forward in the 19th century, and which Carew seems to accept as ‘science’, fails to acknowledge, as many contemporary writers about nature suggest, the richness of ecological mutual interdependence and the revolutionary ideas put forward by Lynn Margulis, co-author of the Gaia Hypothesis (1972) for which James Lovelock has received more than his due credit. Margulis saw evolution as a work of symbiosis and cooperation rather than tooth-and-claw competition.

nature’s capacity for self-regulation. Though, here too, there are no easy answers. Darwinian ‘survival of the fittest’, an ideology that reflected the passion for competition which fuelled the great capitalist leap forward in the 19th century, and which Carew seems to accept as ‘science’, fails to acknowledge, as many contemporary writers about nature suggest, the richness of ecological mutual interdependence and the revolutionary ideas put forward by Lynn Margulis, co-author of the Gaia Hypothesis (1972) for which James Lovelock has received more than his due credit. Margulis saw evolution as a work of symbiosis and cooperation rather than tooth-and-claw competition.

We must, Keggie Carew argues, learn to respect the ways of nature left unto herself. Many instrumental and manipulative human attempts at saving species – animals or plant – have misfired as they didn't take account of nature’s own ‘intelligence’. Let's face it, we are not the smartest creature on earth. Our perspective – a form of intellectual colonialism – focuses in a way that all too often excludes an all-encompassing view of the whole. We need to re-evaluate what intelligence is all about, not least before we get carried away by a form of intelligence whose artificiality could primarily be the product of obsolete, narrow-focused thinking.

Keggie Carew might have written about the work of Ian McGilchrist. He suggests that our culture, reaching back way beyond Descartes to the ground-breaking classifications of Aristotle, is dominated by a predominantly left-brain view of the world. Simply put, McGilchrist writes that we focus primarily on analysing and manipulating the parts rather than taking in a wider view. It’s with this wider view that we may develop a new kind of intelligence, one that goes beyond mere intellect. In this way, animals would escape from the prison of our human perspective. McGilchrist isn't alone in pointing this out. Helen Taylor, an archaeologist and sociologist who works out of Cambridge and Strathclyde, has a new take on human evolution: from earliest times, she argues, there have been two kinds of intelligence, one that exploits and manipulates on the basis of existing knowledge and experience, and another, which she calls the “explorer mind”, an adventurous and open-minded approach that takes much more into consideration than does the mind of habit and tradition. This, she argues, is the kind of intelligence that will enable humanity to find creative solutions that are attuned to the intelligence of animals, and the consciousness that would seem to connect all living things – not just to the beasts.

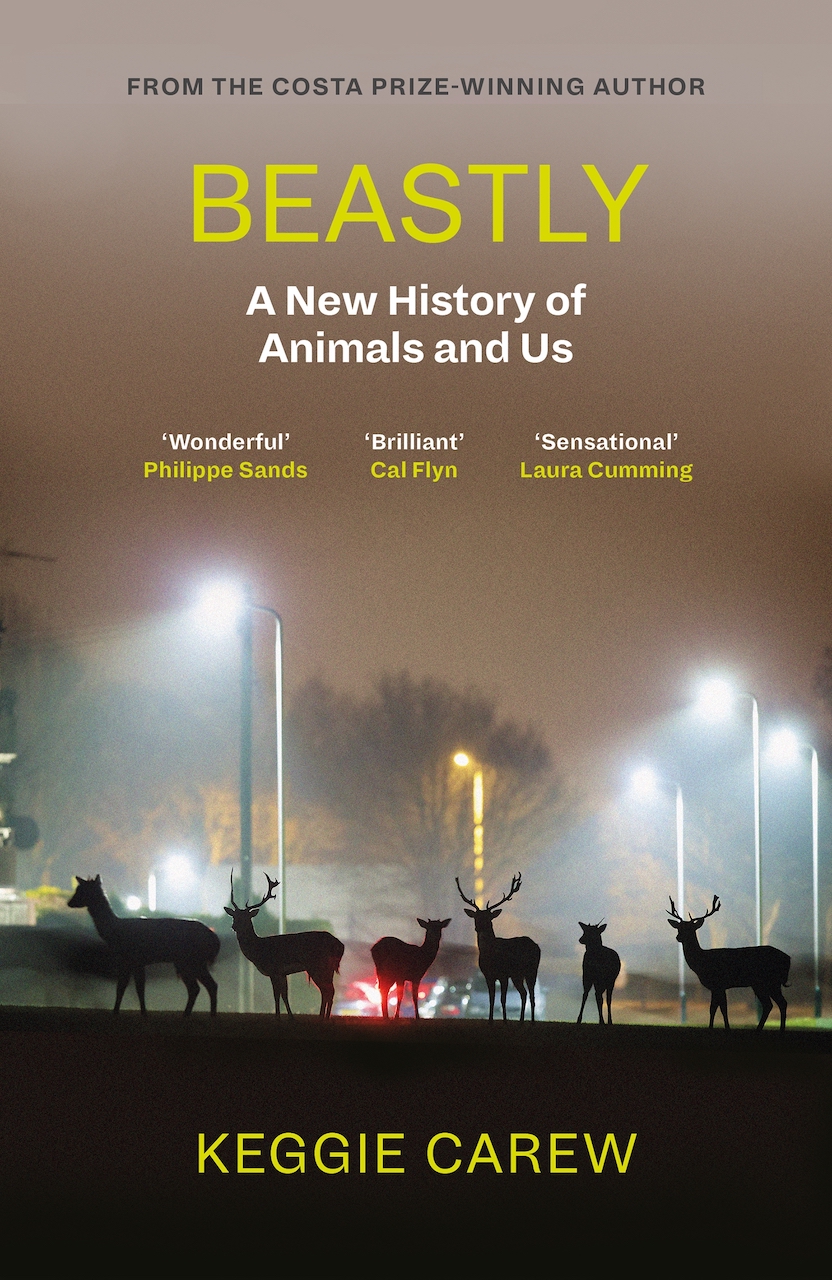

- Beastly, A New History of Animals and Us by Keggie Carew (Canongate, £20)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Comments

Thank you for this review. I