The more Wayne McGregor’s superb Woolf Works is staged, the richer it seems to become. It has started a third run at Covent Garden since its premiere there in 2015, which, considering the house lost over a year of performances, is some achievement. It is the mark of an instant modern classic.

The evening begins with the crystal-clear clipped tones of Virginia Woolf herself, recorded by the BBC in 1937, reading from her essay On Craftsmanship. It’s an uncanny start, like being lectured by a ghost. The essay considers the writer’s use of words, and decides new coinages won’t work with an “old” language like English, you have to make it work for you as it is.

This could almost be a guide to McGregor’s conception of Woolf Works, which has taken the “old” idea of a narrative ballet but reinvented it. What McGregor and his key collaborator, composer Max Richter, have fashioned is something much more compelling than an adaptation: a distillation of three of the novels, one per act, each with a different ethos and sound world. Similarly, the piece uses movement that echoes classical stylings yet is ultimately its own thing.

Alessandra Ferri (pictured right), now 59, is the focal character bookending the acts. (Natalia Osipova and Marianela Nunez dance the role later in the run.) McGregor first intended the role for Ferri, and it’s a perfect fit. She has the ideal combination of qualities for it, able to register an inner turbulence while outwardly impassive, her soulful eyes often cast down, always dignified, almost serene. When she gives in to her emotions, her elegant dancing is all the more impressive for both its total commitment and its control. She makes you see the virtue of the precept that less is more.

Alessandra Ferri (pictured right), now 59, is the focal character bookending the acts. (Natalia Osipova and Marianela Nunez dance the role later in the run.) McGregor first intended the role for Ferri, and it’s a perfect fit. She has the ideal combination of qualities for it, able to register an inner turbulence while outwardly impassive, her soulful eyes often cast down, always dignified, almost serene. When she gives in to her emotions, her elegant dancing is all the more impressive for both its total commitment and its control. She makes you see the virtue of the precept that less is more.

But who is this character she plays, who disappears entirely for the second act? In the first act, "I now, I then", inspired by Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, she is nominally the older Clarissa Dalloway, married to steady besuited Richard (Gary Avis), but plagued by memories of Peter (William Bracewell) and Sally (Francesca Hayward). Poignantly, both the older Clarissa and her younger self (Yasmin Naghdi) dance alongside each other with Sally. The set (by Ciguë) is three giant frames, which slowly revolve as characters lurk on them, watching the others.

Meanwhile, we see separately Septimus (Calvin Richardson), who has returned from the trenches to his wife Rezia (Anna Rose O’Sullivan); he’s a damaged man who has visions of his dead, much loved comrade Evans (Joseph Sissens). As the act draws to an end, Septimus is readying to jump from a window, a suicide theme that projects us forward to the third act, where the suicide is Woolf’s own.

The music here is simple and sober yet increasingly lush. In each act, Richter powers the action along with waves of sounds, minimal at first, then building layer upon layer. In the first act, the West End’s street sounds and tolling bells slowly grow into a theme that sweeps the permutations of dancers along, fading back at the end, as Ferri is left alone in her garden, performing a pensive solo.

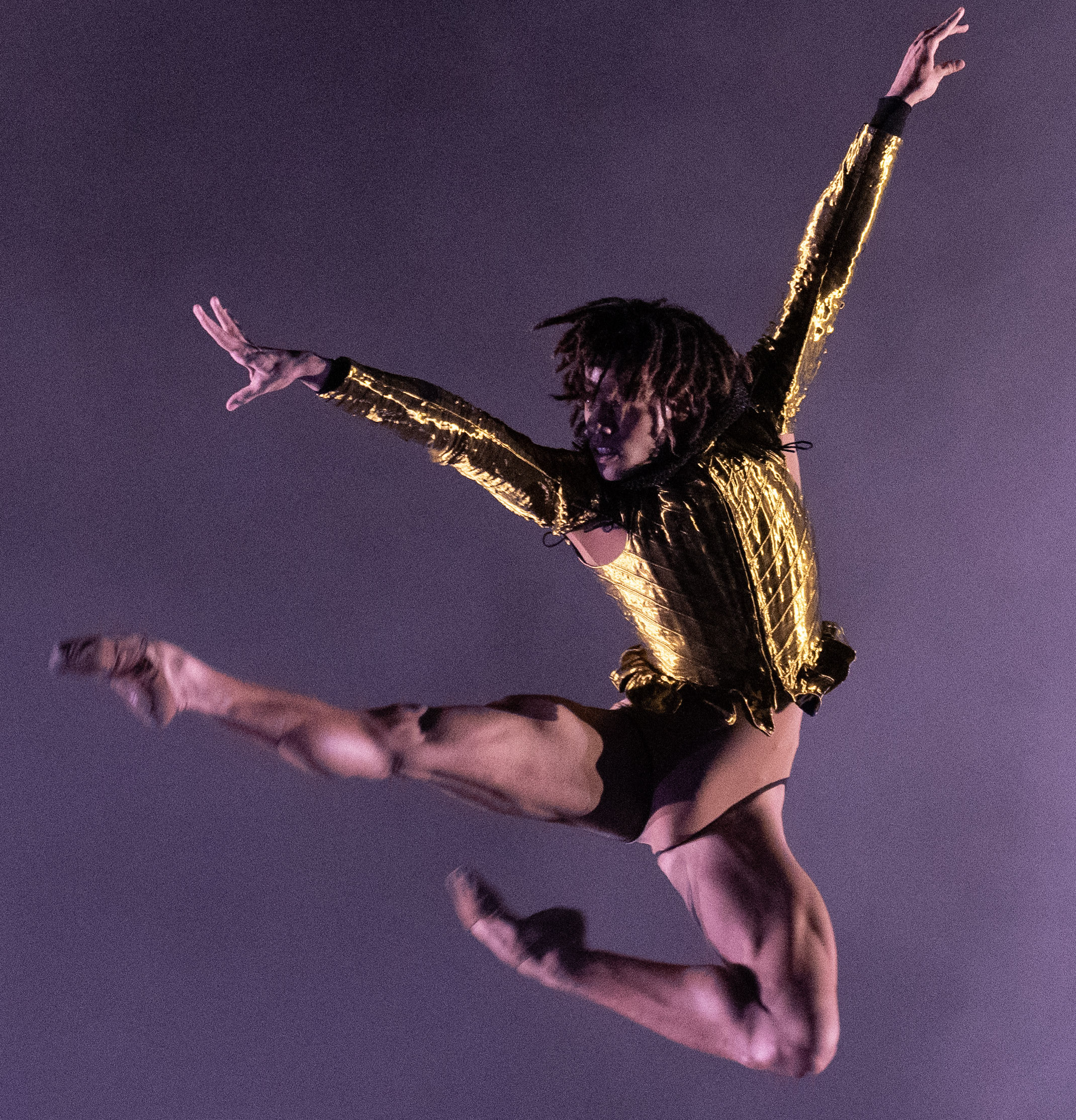

Richter’s music is the perfect grounding for McGregor’s choreography to grow on. Its signature move is a breathtaking sequence of lifts that slide effortlessly into the next, here varied so that each duet has its own flavour and standout moments: exuberant star-jumps for the younger Clarissa, springy bounces for Sally. Meanwhile, Septimus collapses and slumps, with Evans spinning onstage, supporting him briefly, but then spinning offstage even more wildly. (In such an excellent lineup, it’s hard to choose one dancer, but Sissens pictured below is electrifying in both this act and the next.)

The second act, "Becomings", switches us to a dark nowhereland (design by We Not I) lit by ever-changing laser beams, where a squad of androgynous dancers appears in black and gold ruffs, tutus and panniered overskirts that eventually mutate into flesh-coloured leotards. This is the world of Orlando, where time and gender are fluid, as are the moves, which grow increasingly frenetic (and sexy), all boggling extensions and leaps. The music is like a sci-fi film’s, with jangling harpsichord sounds and electronic burbling. All the dancers, who include the excellent principal Fumi Kaneko alongside members of the corps, execute the dynamic choreography with full force..

The second act, "Becomings", switches us to a dark nowhereland (design by We Not I) lit by ever-changing laser beams, where a squad of androgynous dancers appears in black and gold ruffs, tutus and panniered overskirts that eventually mutate into flesh-coloured leotards. This is the world of Orlando, where time and gender are fluid, as are the moves, which grow increasingly frenetic (and sexy), all boggling extensions and leaps. The music is like a sci-fi film’s, with jangling harpsichord sounds and electronic burbling. All the dancers, who include the excellent principal Fumi Kaneko alongside members of the corps, execute the dynamic choreography with full force..

In the third act, "Tuesday", the pace slows right down, its music marked by gently swelling strings and xylophone tinklings, amid which the ethereal sound of a soprano (Anush Hovhannisyan) starts to soar. The inspiration here is The Waves, and the set is aptly dominated by a stage-wide projection (by Ravi Deepres) of a monochrome churning sea in the slowest slow-motion, waves which Ferri’s character – now a version of Woolf herself, whose suicide note is heard in a voiceover by Gillian Anderson – is gradually sucked into.

This sequence has to be one of the most inventive in contemporary ballet. McGregor creates a company of sea creatures, designated visually just by their white spidery head-pieces but distinctive in their movements, who toss and tumble Ferri in swooping lifts and fish dives, until she is gradually submerged among them and comes to a standstill, arms outstretched. Bracewell then arrives to partner her in a final duet, before leaving her onstage alone again, as at curtain up.

Richter’s music has powered the piece to this moving conclusion, sweeping it along to crescendoing pitches of emotion along the way. He and McGregor are an ideal team, and the uniformly impressive Royal Ballet dancers do them proud. It’s probably too much to expect Ferri to dance at the next revival, but don’t miss her if she does.

Add comment