Japanese director Hirokazu Kore-eda is a master of family drama, carrying on the traditions of his illustrious predecessors Yasujiro Ozu and Mikio Naruse. But these are not films of raised voices or open conflict, rather highly nuanced studies of the emotional dynamics between parents and children – differences across the generations – or partners whose relationships have cooled. There’s always a gently melancholic tinge, and Kore-eda has a particular gift for working with his child actors, movingly presenting their point of view on the issues that divide the adults who surround them.

In addition, Kore-eda has assembled almost a company of actors with whom he has regularly worked from film to film, creating the effect almost of a family in itself. It makes for a rare intimacy. In After the Storm his mother and son protagonists are played by Kirin Kiki and Hiroshi Abe, who played similar roles in his 2008 masterpiece Still Walking. Abe plays Ryota, something of a prodigal who has come back into the life of his mother, Yoshiko, after the death of his father. Well-aware of her son’s shortcomings – which seem to repeat many of those she put up with from her late husband – she accepts him without judgment.

Abe’s hangdog face is an expressive joy in itself

The same can’t be said for his estranged wife, Kyoko (Yoko Maki). Their meetings, arranged formally for the father to see his young son Shingo (Taiyo Yoshizawa, another child role masterfully drawn out by the director), are coloured every time by his failure to produce the maintenance payments he is supposed to. However, the closeness between father and son is powerfully felt, and reciprocal, even if Ryota struggles to give him the kind of gifts being offered by Kyoko’s new partner (and, perhaps, husband-to-be).

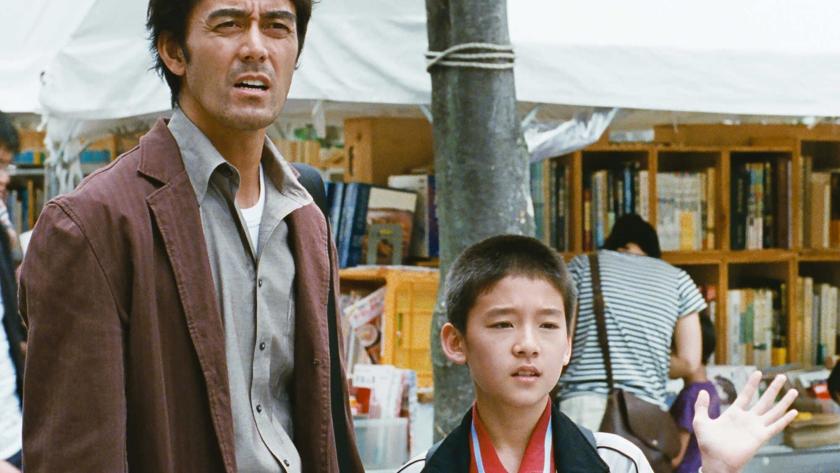

The context of divorce is one Kore-eda explored in his 2011 I Wish, while the nature of family loyalties were at the centre of his more complicated Like Father, Like Son, from 2013. But there’s something of a new element in After the Storm, a degree of rather macabre comedy less familiar from his work. Some 15 years earlier Ryota had published an acclaimed first novel, but his literary career has clearly stalled. For some time he’s been working for a detective agency, ostensibly claiming it as research for a new book, but it’s clear that he’s staying there because it’s the only source of the cash he needs to keep a roof over his head.

As well as the more mundane tasks of detective work like lost pets, the agency seems to specialise in divorce work, following unfaithful partners for evidence that they are cheating on their marriages, and the like. However, Ryota has made a personal speciality of exploiting such cases for his own ends – he’s an adept at blackmail, or selling incriminating evidence to the guilty party, even shaking down a kid for money to hush up a liaison. Abetted by a fresh-faced colleague, he’s unscrupulous in almost every respect, yet the repercussions of his actions never seem to catch up on him (in a different movie genre, he’d be up making some nasty enemies). He’s doing this, we discover, to feed his longterm gambling habit.

As well as the more mundane tasks of detective work like lost pets, the agency seems to specialise in divorce work, following unfaithful partners for evidence that they are cheating on their marriages, and the like. However, Ryota has made a personal speciality of exploiting such cases for his own ends – he’s an adept at blackmail, or selling incriminating evidence to the guilty party, even shaking down a kid for money to hush up a liaison. Abetted by a fresh-faced colleague, he’s unscrupulous in almost every respect, yet the repercussions of his actions never seem to catch up on him (in a different movie genre, he’d be up making some nasty enemies). He’s doing this, we discover, to feed his longterm gambling habit.

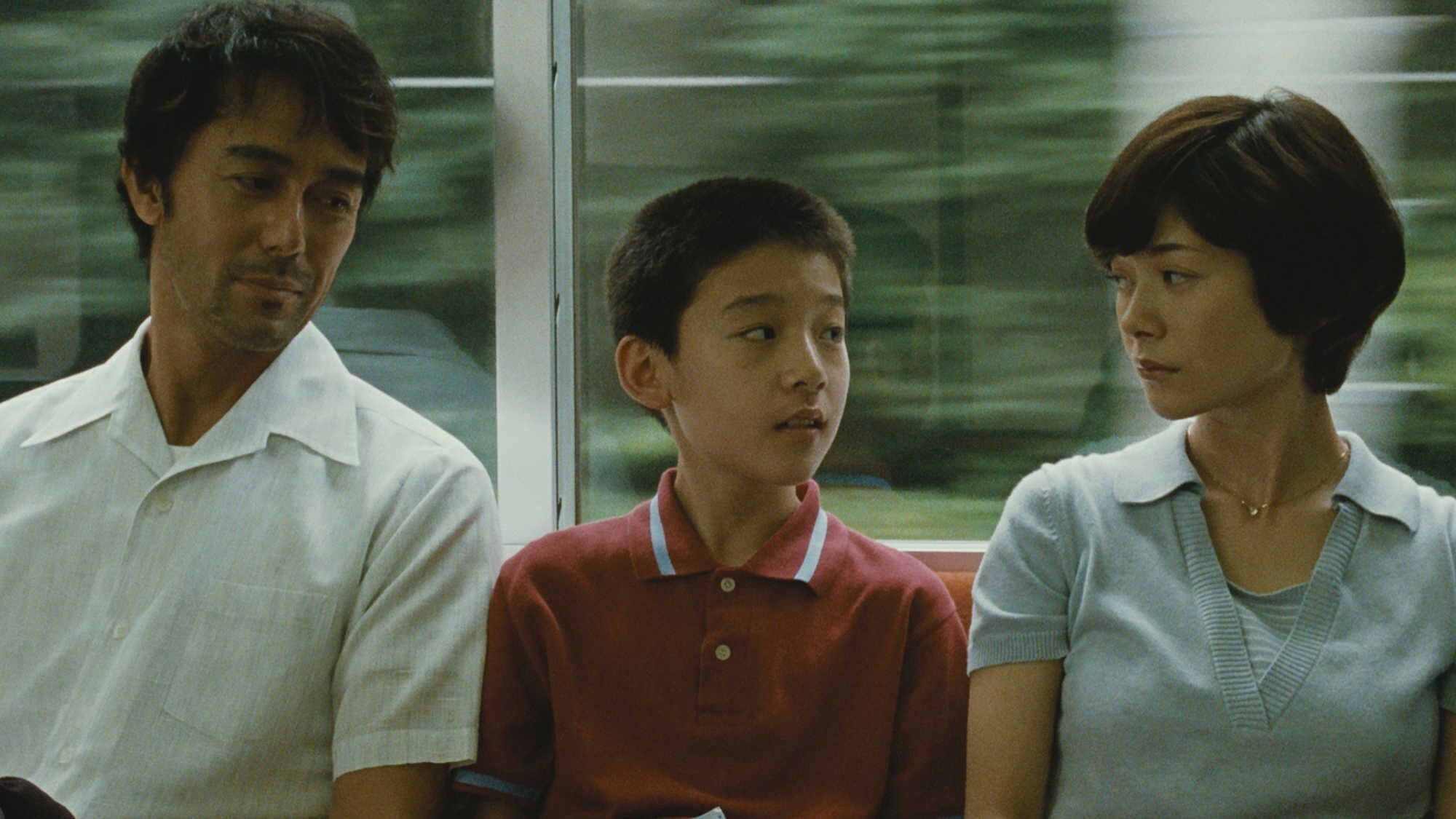

He has even been sleuthing on Kyoko, as well as drawing facts about her new life out of Shingo. All of this is background context for a day in which the paths of the trio cross, first as father and son spend time together in the city, then when the three of them end up in Yoshiko’s humble flat. We’ve been aware of typhoon warnings throughout the film, and when one finally breaks, they are forced to spend the night there, giving rise to a series of conversations that reassess the past, the hopes with which each character had started, and where they have ended up. The storm may be raging outside, but its still centre for Kore-eda is playing out with a potent intimacy within these cramped apartment walls. (Pictured below: Hiroshi Abe, Taiyo Yoshizawa, Yoko Maki)

It gives rise to a moving denouement, one which even offers hints, however tentative, of hope for the future. Yoshiko may be aware of her encroaching end (“new friends at my age only mean more funerals”), yet hasn’t lost interest in life, even joining a classical music group to discuss Beethoven (she has a soft spot for the teacher, too). Abe’s hangdog face (pictured, top) is an expressive joy in itself, and we somehow can’t help feeling for this undoubted scamp who nevertheless doesn’t seem to mean any harm (“How did my life get so screwed up?” he asks himself). Yoshizawa as the sensitive Shingo beautifully captures the complicated nuances of the child’s love for his unreliable dad, which makes for a loyalty that endures regardless of what he gets up to.

It gives rise to a moving denouement, one which even offers hints, however tentative, of hope for the future. Yoshiko may be aware of her encroaching end (“new friends at my age only mean more funerals”), yet hasn’t lost interest in life, even joining a classical music group to discuss Beethoven (she has a soft spot for the teacher, too). Abe’s hangdog face (pictured, top) is an expressive joy in itself, and we somehow can’t help feeling for this undoubted scamp who nevertheless doesn’t seem to mean any harm (“How did my life get so screwed up?” he asks himself). Yoshizawa as the sensitive Shingo beautifully captures the complicated nuances of the child’s love for his unreliable dad, which makes for a loyalty that endures regardless of what he gets up to.

Played in a plangent, minor key, After the Storm is rich in whimsy, with Hanaregumi’s score drawing plentifully on whistling, to give the sense of an everyday amble through life’s unpredictabilities. It’s set in a dormitory suburb of Tokyo, Kiyose, where Kore-eda spent part of his youth, a slightly down-on-its-luck neighbourhood that life seems to have in some sense passed by, just as it has the director’s protagonists. It’s a perfect location for a film that ruefully captures a sense of life's tribulations, as well as its occasional small joys.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for After the Storm

Add comment