It’s quite unusual for the extras on a DVD release to talk down the main attraction. But that appears to be the case with the BFI’s package for Equus, Sidney Lumet’s 1977 adaptation of Peter Shaffer’s acclaimed stage play.

“I didn’t like it,” mumbles actor Peter Firth of the film (in a new audio interview), having originated the part of disturbed youngster Alan Strang on stage in London, before taking the play to Broadway, then onto screen. And even Lumet, in a 1981 Guardian lecture, dismisses his work as a “brave attempt that should never have been made”.

Their misgivings relate in part to an anomaly that has always attached itself to Equus. Usually a film adaptation of a play is criticised for being “too theatrical”, for failing to ditch its stagey antecedent; here, Lumet was criticised for attempting to bring cinematic naturalism to the mix, notably to the infamous scene in which Strang blinds six horses with a metal spike.

On stage the horses were played by men wearing huge equine heads; on the film’s release it was widely felt that in introducing real horses and using screen effects and editing to depict their gory demise, Lumet turned people’s stomachs at the expense of the play’s mythic quality.

I would largely disagree with the naysayers. Today Equus might seem talky, Seventies-drab, overwrought; and yet it’s also a compellingly strange film. Shaffer’s rich mix of psychiatry and theology, sexual confusion and violence, a young anti-hero trapped in the pincer movement of parental fuckwittery and medical presumption, and the matching existential crises of teenage boy and middle-aged therapist exerts a perverse, fascinating, thought-provoking hold.

I would largely disagree with the naysayers. Today Equus might seem talky, Seventies-drab, overwrought; and yet it’s also a compellingly strange film. Shaffer’s rich mix of psychiatry and theology, sexual confusion and violence, a young anti-hero trapped in the pincer movement of parental fuckwittery and medical presumption, and the matching existential crises of teenage boy and middle-aged therapist exerts a perverse, fascinating, thought-provoking hold.

And then, of course, there’s Richard Burton.

This is one of Burton’s greatest screen performances. It’s also one that adds an irony to the whole debate about stage and screen, given you could close your eyes through every one of his magnificent monologues and still feel the forbidding power of Shaffer’s writing. With Burton, we could almost make do with radio; almost, but not quite, because the man had a rapport with the camera, too, and an unacknowledged lack of vanity that allowed every pockmark to yell of his inner torment. If there were one reason to see this, it would be the Welshman at his coruscating best.

Burton is Martin Dysart, a child psychologist at a provincial hospital. A friend and magistrate (Eileen Atkins) has just tried the case of the 17-year-old stable boy Alan, shortly after his inexplicably evil deed. The lad is now on remand. She wants Dysart to treat the boy, discover his motivations, in the hope of a lenient sentence.

Although initially reluctant, Dysart takes on the task with impressive vigour, quizzing Alan’s extremely liable parents (religious zealotry from one, sexual repression the other) and outraged, distraught employer, and playing a cat and mouse with the boy himself. But the deeper the psychiatrist delves into his patient’s trauma, the more he must confront his loss of faith in his profession, and thereby himself.  Poor Alan has worked himself into a torturous psychological knot, confusing Christ for ‘Equus’, devotion for sexual attraction, with ultimately appalling consequences. Dysart understands that in forcing Alan to confront his wrongdoing, and in untying those highly personalised knots, he’ll effectively dispossess the lad of a striking individuality.

Poor Alan has worked himself into a torturous psychological knot, confusing Christ for ‘Equus’, devotion for sexual attraction, with ultimately appalling consequences. Dysart understands that in forcing Alan to confront his wrongdoing, and in untying those highly personalised knots, he’ll effectively dispossess the lad of a striking individuality.

“If normal is the indispensable, the murderous god of health, then I am its priest,” spits Burton. Who knows, could these also be the words of an actor who believes he’s sold his own individuality to the Hollywood machine and, in particular, for money? Burton played Dysart on stage and apparently fought hard to win the role on screen; it perhaps spoke to him more than we can know.

I think Lumet, one of cinema’s most versatile directors, judged all this pretty well, not least by being led by the text. In his hands, the onstage monologue becomes the warts-and-all close-up and mid-shot, Burton hypnotic as he breaks the fourth wall to ask, “What am I doing here?” and revealing that, “I’m lost. I’m wearing that horse’s head myself.”

The director also creates an intriguing juxtaposition between the drab period interiors and Alan’s distinctly odd, romanticised relationship with horses, from his first encounter with one on a beach (Firth working wonders as a pre-pubescent) to the long sequence in which the young man rides one of the stable horses naked in the night. All told, it’s a potent portrait of a personality distorted by all the wrong influences and compulsions.

The Strang parents are well played by Joan Plowright and, particularly, Colin Blakeley (both of whose characters you’d like to give a good slap) and Eileen Atkins an appealing presence as the friend and idealist who would make a far better partner than Dysart’s wife. In the small but key role as Alan's fellow stable worker, Jenny Agutter (pictured below with Firth) was at that period in her early career when she offered her slightly posh girl-next-door image as a highly effective counterpoint to challenging material.  As for Firth, he knew the part inside out by the time he faced his third Dysart (having played against Alec McCowen and Anthony Hopkins on stage). Seeing this again, it’s remarkable how much he reminds one of the young Malcolm McDowell, another Yorkshireman with an anarchic streak, who 10 years earlier had made his own killer debut in If…

As for Firth, he knew the part inside out by the time he faced his third Dysart (having played against Alec McCowen and Anthony Hopkins on stage). Seeing this again, it’s remarkable how much he reminds one of the young Malcolm McDowell, another Yorkshireman with an anarchic streak, who 10 years earlier had made his own killer debut in If…

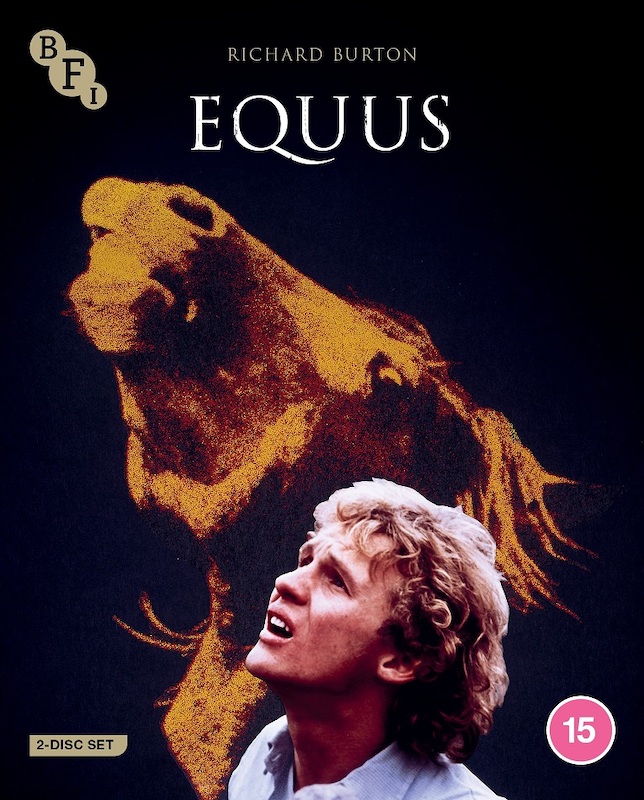

Firth here is cherubically beautiful, with his own ‘mane’ lending an appropriately Dionysian aspect to the character (Shaffer’s busy script airs that old battle between the Apollonian and Dionysian). He has fun with Alan’s initial hostility towards the psychiatrist – rattling out a string of advertising ditties as defensive barbs – and is movingly vulnerable as the lad slowly allows Dysart in.

Both Firth and Burton were Oscar nominated, as was Shaffer for his own adaptation; one of Britain’s most revered playwrights, he'd later win for the more generally lauded film of his Amadeus.

This limited edition Blu-ray offers a plethora of extras. Some are a little perplexing. The audio interview with Firth (now best-known as gloomy spymaster Harry Pearce in Spooks) is played over a stills gallery from the film that begins to feel stretched; and while Firth is an engaging interviewee, the conversation focuses too much on his experience as a young man thrust into the spotlight, too little on the themes and process of the work; and I’d have liked more probing into his comparison of three such different, though equally formidable co-stars.

The interview with Lumet is also presented in audio only, and this time it’s a mistake to have a career conversation playing over one film, Equus, which features just briefly as a subject.

Tony Palmer’s 1998 documentary, In From the Cold? A Portrait of Richard Burton offers a different kind of frustration, in that while charting the well-trod topic of his supposedly wasted talent, it does too little to explore and enjoy the great deal of brilliant work that he did produce.

But one can’t fault the eclecticism on show with these extras, which include a 1951 public information film about farm horses and a 1940 documentary short about the role of religion in British society at the time. And it all feeds into the experience of a feature that singularly refuses to fit into a box, horse or otherwise.

Add comment