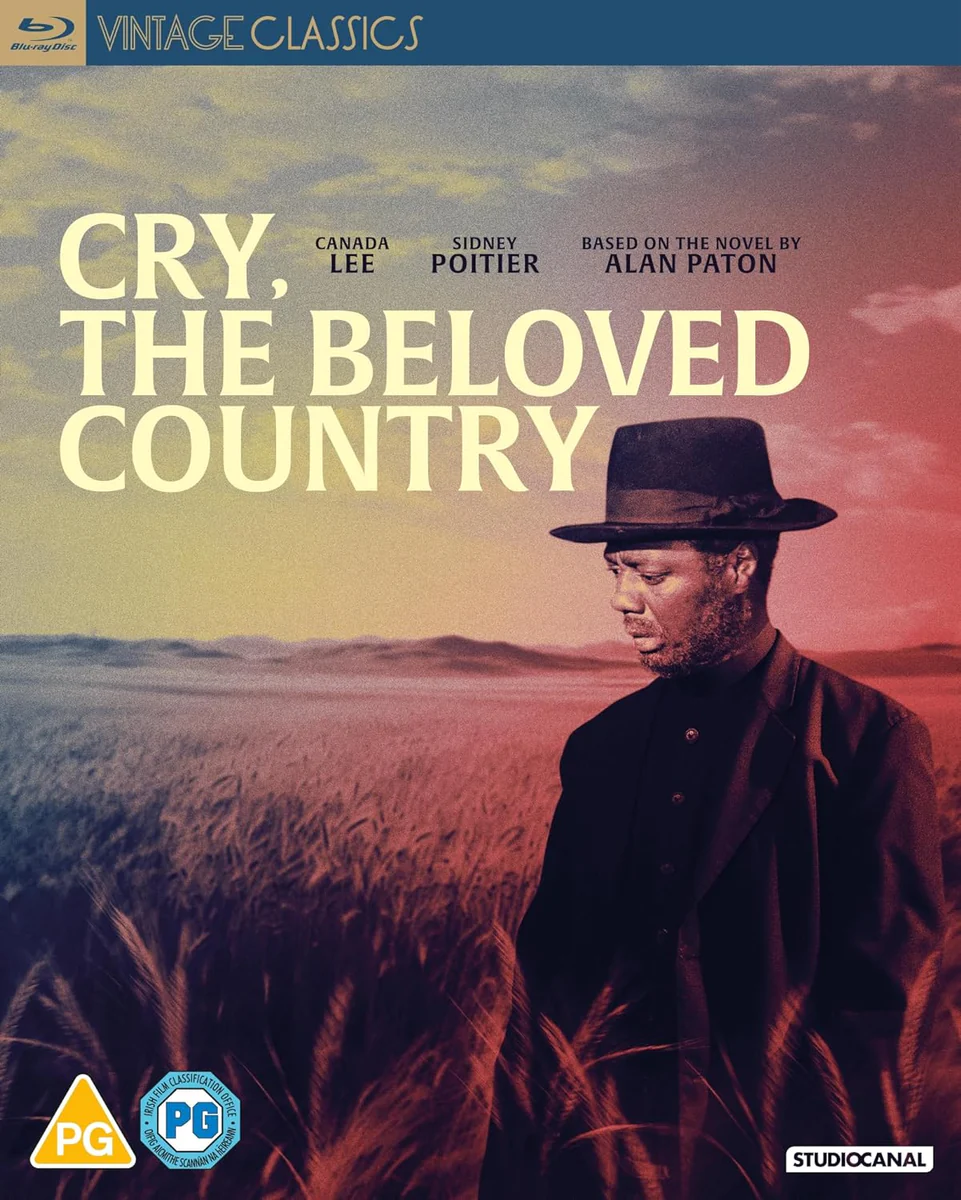

Movie Blu-rays and DVDs brim with superficially engaging extras that frequently fail to illuminate the main attraction. The opposite is true of Cry, the Beloved Country, which has been restored in 4K and newly released in StudioCanal’s Vintage Classics series of British films. The disc’s extras have been carefully chosen to contextualise Zoltán Korda’s potent 1951 drama as the first film to condemn apartheid.

The white activist Alan Paton’s bestselling novel, published in Britain and the United States in February 1948, warned the world about the clampdown looming for the black majority in South Africa. Four months later the Reunited National Party won the general election and began implementing its policy of authoritarian racial segregation and discrimination.

A director passionate about Africa, Korda hired the blacklisted (and at the time uncredited) Hollywood screenwriter John Howard Lawson to work with Paton on Cry, the Beloved Country's script; Lawson had previously woven a socialist subtext into Korda’s Sahara (1943). When Korda brought his African-American stars Canada Lee and Sidney Poitier to film exteriors in South Africa, he had to pass them off as his indentured servants; interiors were filmed at Shepperton Studios in Surrey.

Though it has the quality of a biblical parable, Cry, the Beloved Country is reminiscent of the era’s social problem pictures thanks to Robert Krasker’s black and white cinematography. It begins as a documentary, the narrator explaining that white control of arable land has spurred black migration to Johannesburg.

Stephen Kumalo (Lee), an unworldly Christian pastor in his early sixties, ventures to the urban well of corruption from his home in rural Natal to find his long-silent sister Gertrude (Ribbon Dhlamini) and son Absolom (Lionel Ngakane). Travelling by train, Stephen sees the mountainous “tailings” of toxic mine waste from gold extraction that has benefitted indigenous South Africans nothing

Stephen Kumalo (Lee), an unworldly Christian pastor in his early sixties, ventures to the urban well of corruption from his home in rural Natal to find his long-silent sister Gertrude (Ribbon Dhlamini) and son Absolom (Lionel Ngakane). Travelling by train, Stephen sees the mountainous “tailings” of toxic mine waste from gold extraction that has benefitted indigenous South Africans nothing

Helped by a no-nonsense local clergyman (Poitier), Stephen tracks down Gertrude, who has become a prostitute in a squalid black ghetto. Before he can find Absolom, the first in a series of connected tragedies occurs – the racist alienation of young black men having an all too familiar outcome.

These events lead Stephen to a symbolic rapprochement with the grieving white farmer James Jarvis (Charles Carson), a rich neighbour his own age, who renounces his bigotry and starts to work for the communal good; Joyce Carey, who played the station bartender in Brief Encounter (1945), plays Jarvis's ailing wife.

Facing bereavement himself, the devout Stephen knows that, though the lord taketh away, he also giveth – he will become the grandfather of the child carried by Absolom’s teenage girlfriend (Vivien Clifton). Acting in his last film, Lee was formidable, whether rendering Stephen’s personal anguish or his hopes for universal brotherhood.

But Lee suffered a heart attack at the end of filming in South Africa and was flown to London for a surgical procedure in January 1951. Himself a Civil Rights activist blacklisted as an “outstanding fellow traveller” (and harassed by the FBI for not betraying his friend Paul Robeson as a communist), Lee died of kidney disease in Manhattan at age 45 in May 1952, two weeks after Cry, the Beloved Country’s UK release.

The superb extras include an eye-opening commentary on Lee’s eventful life by his biographer Mona Z Smith. A lifelong activist, Lee was a musician, jockey, and boxer before he was an actor. He starred as Bigger Thomas in the stage version of Richard Wright’s Native Son, directed on Broadway by Orson Welles. Absolom's fate in Cry, the Beloved Country recalls Bigger’s, both works exposing how systemic racism stacks the odds against black men from birth.

Newsreel footage from Cry, the Beloved Country’s Johannesburg premiere at the Colosseum cinema shows that not a single black person was in attendance owing to segregation. Prime Minister DF Malan, the Afrikaner nationalist and apartheid absolutist, was present to shake hands hypocritically with Paton. The author sat next to Malan’s wife during the screening and later reported in his autobiography, Towards the Mountain: “She was clearly disturbed and said to me, ‘Surely, Mr. Paton, you don’t really think things are like that.’ I said to her: ‘Madam, I lived in that world for 13 years,’ but I did not add, ‘and you, madam, have never seen anything of it at all.’"

In a Reuters interview with Paton filmed in 1962, when he anticipated being put under house arrest for his activism, he vents his wrath at the white supremacist government and makes a heroically defiant statement about his refusal to knuckle under.

In a Reuters interview with Paton filmed in 1962, when he anticipated being put under house arrest for his activism, he vents his wrath at the white supremacist government and makes a heroically defiant statement about his refusal to knuckle under.

A rich archival feature on cinema under apartheid traces the influence of Donald Swanson’s Jim Comes to Jo’burg (aka African Jim, 1949), the first South African film with an all-black cast. There is also a remarkable interview with Ngakane (1928-2003), who not only played Absolom but was Korda’s assistant director. (Pictured above: Lee, Poitier, Michael Goodliffe as Absalom's reformatory supervisor, and Vivien Clifton)

Exiled to Britain, Ngakane continued to act and directed documentaries on apartheid and the award-winning dramatic short Jemima & Johnny (1965), inspired by the Notting Hill race riots. He attacks Richard Attenborough’s Cry Freedom (1987) for telling the story of Steve Biko’s murder through his friendship with the white journalist Donald Woods. Geoffrey Keen and Michael Goodliffe play decent whites in Cry, the Beloved Country, but they don't detract from Stephen Kumalo's journey or assuage his pain.

Add comment