To create this strikingly original portrait of the man some (though not Frank Sinatra) liked to call "the greatest movie actor of all time", writer/director Stevan Riley has plundered a remarkable trove of Brando's own audio recordings and used them to create a kind of self-narrating autobiography. The notion that we're hearing Brando telling his own story from some post-corporeal ether is reinforced by the device of opening the film with a computerised 3D talking head, based on a digital image of Brando's own head made in the 1980s. "Actors are not going to be real," it predicts, in Brando's voice. "They're going to be inside a computer. You watch."

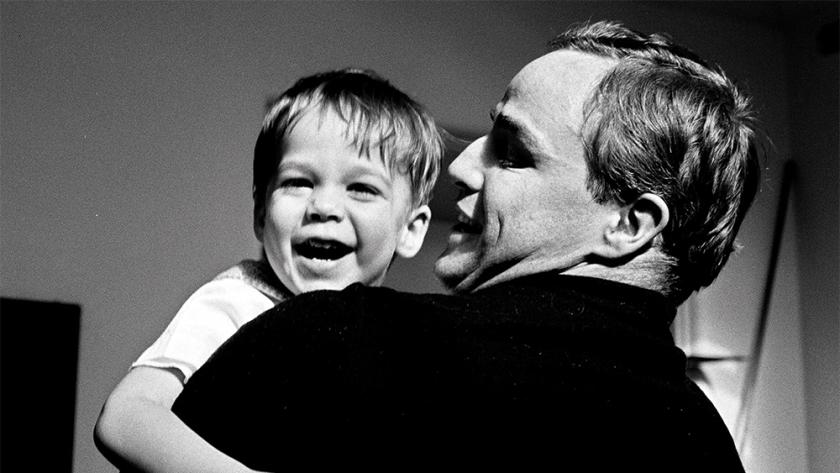

Via this crafty sleight of hand, Riley slips us into a dreamlike world where we experience the main events of Brando's life and career through a seamless montage of scenes from his films, home movies, news clips and interviews. As the narrative moves across events and phases of his life, it's shaped by Brando's commentary. The fact that the variable quality of the soundtrack reveals how it has been assembled from recordings made across several decades gives the film a layered resonance eminently fitting for such a massive yet enigmatic figure (Brando in On the Waterfront, pictured below).

Much as Brando loathed stardom (he resented how it prevented him from leading a normal life) and strenuously avoided public exposure, privately he was a compulsive worrier and self-analyser. Much of the voice-over has been lifted from the self-analysis sessions Brando conducted on himself, and he talks with painful frankness about the way his macho, bullying father used to beat him, and his shame at how his alcoholic mother was known as "the town drunk". Yet he also felt a great tenderness towards her, her sense of independence and her artistic gifts, which included being an actress and theatre administrator. After he became famous, Brando used to do TV interviews with his father as a sort of mutually mocking double act. We see him laughing about it, but only through gritted teeth.

Much as Brando loathed stardom (he resented how it prevented him from leading a normal life) and strenuously avoided public exposure, privately he was a compulsive worrier and self-analyser. Much of the voice-over has been lifted from the self-analysis sessions Brando conducted on himself, and he talks with painful frankness about the way his macho, bullying father used to beat him, and his shame at how his alcoholic mother was known as "the town drunk". Yet he also felt a great tenderness towards her, her sense of independence and her artistic gifts, which included being an actress and theatre administrator. After he became famous, Brando used to do TV interviews with his father as a sort of mutually mocking double act. We see him laughing about it, but only through gritted teeth.

Brando also laments his own lack of education, saying he "wished he knew more". He was much influenced by acting coach Stella Adler (a ringer for a young Angela Lansbury, judging by clips included here), who introduced him to the Stanislavski method. Watching him again in his protean prime, in landmark pieces like A Streetcar Named Desire and On the Waterfront, the feral energy and sexual charge still come peeling off the screen in waves ("past a certain point the penis has its own agenda," remarks the actor). But it would be misguided to mistake the actor for the role, and Brando was explicit about how much he detested – and how little he personally resembled – his character Stanley Kowalski in Streetcar.

After his great early triumphs, Brando never again seemed certain of his direction. His performance as Fletcher Christian in Mutiny on the Bounty (1962) represents a watershed, the point where he tipped from screen icon to unmanageable prima-donna. Here, though, the emphasis is on Brando telling us how he became bewitched by Tahiti and its natives during the Bounty shoot, and how 20-year-old actress Tarita Teriipaia became his third wife.

After his great early triumphs, Brando never again seemed certain of his direction. His performance as Fletcher Christian in Mutiny on the Bounty (1962) represents a watershed, the point where he tipped from screen icon to unmanageable prima-donna. Here, though, the emphasis is on Brando telling us how he became bewitched by Tahiti and its natives during the Bounty shoot, and how 20-year-old actress Tarita Teriipaia became his third wife.

The big comeback pieces are covered – The Godfather (pictured above), Last Tango in Paris and Apocalypse Now, where director Francis Coppola was shocked by Brando's grotesque bulk – but a long string of clunkers is left unremarked. Meanwhile Brando's South Pacific idyll ended in bleakest nightmare, with the couple's daughter Cheyenne committing suicide in 1995, her half-brother Christian having been jailed for killing her boyfriend five years earlier. The news film of Brando trapped in the midst of these horrific events depicts a broken man barely able to carry on.

It's left to Brando to write his own coda, describing himself in the third person: "He's a troubled man, alone, beset with memories, in a state of confusion and sadness, isolation, disorder..." Inside Brando's skull, real or digitised, is not a place you'd have wanted to be.

Add comment