Asti would become the achingly beautiful muse of Before the Revolution, which traces the interlocking romantic and political failure of a 20-year-old bourgeois communist wannabe, Fabrizio (Francesco Barilli), whose dream of “a new sort of man” to inhabit the world is as idealistic as his incestuous love for his hopelessly seductive young aunt, Gina. The film prophesied the collapse of Bertolucci and Asti’s own marriage - in that sense she is Anna Karina to his Godard - but as a symbol of rebellion, however forlorn, it was successful, providing a famous rallying cry in the 1968 student revolt in Paris.

And Before the Revolution is nothing if not the film of a Godardian disciple, a work of enormous ideas and ambivalences, replete with jump cuts (sometimes within shots), stunning close-ups, sloganeering, Breathless-like plein air footage (Fabrizio and Gina seeking each other amid a crowd of milling Parma men) and textual references to auteurs and their movies; Fabrizio even goes to see Godard’s A Woman is a Woman - though we learn that he couldn’t concentrate on it because of his love confusion, and can’t, for that matter, focus on the ensuing conversation with his hilariously boring cinephile friend, who opines, “In 20 years, Anna Karina will be what Louise Brooks is to us now.” There’s a nod to Truffaut, too - Asti doing some delightful shtick with different pairs of glasses in homage to Jeanne Moreau in Jules et Jim.

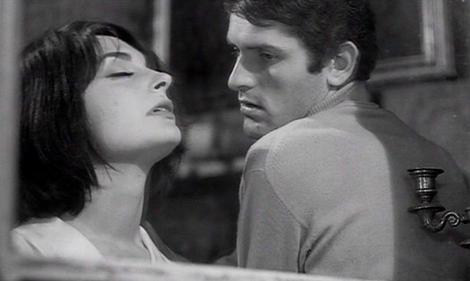

The self-involved Gina (pictured right), who knew Fabrizio as a child, returns to his life shortly after he has embraced communism, has rejected his lovely but dull upper-class fiancée Clelia (Cristina Pariset) - who is fittingly introduced in a montage of basilica statues, the church being synonymous in his view with loss of freedom - and while he is grieving for his handsome friend, Agostino (Allen Midgette). Presumably named for the Alberto Moravia short story and the hero of Pasolini collaborator Mauro Bolognini’s 1962 film version, Agostino is an epicene beauty whose longing for Fabrizio is palpable.

The self-involved Gina (pictured right), who knew Fabrizio as a child, returns to his life shortly after he has embraced communism, has rejected his lovely but dull upper-class fiancée Clelia (Cristina Pariset) - who is fittingly introduced in a montage of basilica statues, the church being synonymous in his view with loss of freedom - and while he is grieving for his handsome friend, Agostino (Allen Midgette). Presumably named for the Alberto Moravia short story and the hero of Pasolini collaborator Mauro Bolognini’s 1962 film version, Agostino is an epicene beauty whose longing for Fabrizio is palpable.

Agostino's off-screen suicide by drowning, attended by semi-naked boys, may signify Bertolucci’s jettisoning of Pasolini’s influence in favor of a more refined poetic style of his own, but it is the most elliptically haunting scene in the film. Subsequently, the aunt's invitation to sin, which equates to Fabrizio’s received revolutionary fervour as sexuality equates to rebellion in later Bertolucci films (including Last Tango in Paris and The Dreamers), is rhapsodically achieved, as is their actual lovemaking, notably through a three-minute shot in which they smooch in close-up in front of his oblivious father and sleeping grandmother. Fabrizio falls in love, and like most young men of 20 experiencing that sensory overload for the first time has no idea how to handle his feelings.

Gina loves Fabrizio back - as the duchess Gina loves her idealistic Napoleonic nobleman-soldier nephew Fabrice in Stendhal’s 1839 novel The Charterhouse of Parma - but she is naturally wiser than he is, as well as more grounded intellectually: as his Marxist mentor Cesare (played by the eminent film critic Morando Morandini) acknowledges, she’s a Proust reader, and she impudently cites Wilde - “Men… rage against materialism, forgetting that there has been no material improvement that has not spiritualised the world, and that there have been few, if any, spiritual awakenings that have not wasted the world’s faculties in barren hopes” - to rebut his pontifications about democracy and freedom. But she is too emotionally fragile to sustain an intense monogamous affair.

In her most revealingly Freudian moment, Gina drops out of a conversation to stand by a window and have an orgasmic panic attack. A practised fatalist, she recognises and, indeed, embodies the nebulousness of desire - “Clouds pursue clouds,” she almost sings, announcing her love for Fabrizio. “You pursue me pursuing you” - which mirrors his vague political views, and she forecasts the end of their brief relationship to herself while looking in a camera obscura at Fontanellata Castle. This self-consciously cinematic device provides the film with fleeting colour images, one of the otherwise humourless Fabrizio cavorting for her benefit on the street below, and another, as she imagines it in the coming September when they’ll no longer be together, at the same spot.

Watch a clip from Before the Revolution

The relationship founders when he finds her having just left a cheap Parma hotel with a man she picked up, having needed someone to talk to (and somehow this is believable), and later when she slaps him for insulting an older male friend of hers, a landowner who is about to lose his heavily mortgaged property by the polluted River Po, by priggishly calling him a privileged hypocrite.

It’s hardly giving anything away to say that it all ends in tears - hers, even though it’s she who leaves him, consigning him to Clelia and his bourgeois destiny. Fabrizio has become bitter but has grown in maturity. “I wanted to fill Gina with vitality. I filled her with anguish,” he tells Cesare. And then, in more or less the same breath, “For me, ideology was something of a holiday. I thought I was living the revolution. Instead, I lived the years before the revolution. Because for my sort it’s always before the revolution.” That line of dialogue was adapted from a Talleyrand quotation - “He who did not live in the years before the revolution cannot understand the sweetness of living" - that Bertolucci uses as an epigraph. One can imagine Fabrizio at 26 bemoaning the 1968 upheavals, before making anaemic love to his wife while fantasising about the mercurial but ineffably sexy aunt of his 20th spring.

- Before the Revolution is now in cinemas

- The Bertolucci season at BFI Southbank until 31 May

Find The Grim Reaper on Amazon

Find The Grim Reaper on Amazon

Add comment