We’ve recently seen how Formula One heroes Ayrton Senna, Niki Lauda and James Hunt can become box office gold, in the form of Senna and Rush.

This is the most frustrating film. It’s probably no fault of the makers, but it’s rare to have to assess a documentary for what it doesn’t have. Over nearly two hours of celebrating the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band Beatles period – late 1966 to their record label Apple taking off in 1968 – there is not a note of the group’s music.

Well, alright, in the opening animated credits you detect a phrasal shimmer of George Harrison’s sitar-driven “Within You Without You”, but that’s it. The score, by Andre Barreau and Evan Jolly, is a confection of atmospherics and rhythms that could be the Beatles but absolutely isn’t.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is the most famous album of the 20th century. The LP practically defines the last part of it. On paper, it makes real sense to release a half-century anniversary documentary about the trailblazer. But it’s asking a lot of someone aware of the Beatles brand and familiar with, say, a handful of their best-known songs to be amused by or engaged in chitchat about – the here non-heard – “Being for the Benefit of Mr Kite!” or “Lovely Rita” if they don’t know them. Unfortunately, that is a legacy downside of the group’s global reach: Apple Corps, representing the interests of Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr and the estates of John Lennon and George Harrison, will – putting it simply – just say no to anyone seeking to broadcast or exploit Beatles originals in the public domain, unless four parts are in total agreement and involved. So it was that, by contrast, Ron Howard last year stole a march on Alan G. Parker, maker of this new film, by having – with the help of producer George Martin’s son Giles and presumably Apple – original live sound in Eight Days A Week, about the touring years, as well as new spoken contributions from McCartney and Starr. Neither appears in It Was Years Fifty Ago Today! Who does?

Unfortunately, that is a legacy downside of the group’s global reach: Apple Corps, representing the interests of Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr and the estates of John Lennon and George Harrison, will – putting it simply – just say no to anyone seeking to broadcast or exploit Beatles originals in the public domain, unless four parts are in total agreement and involved. So it was that, by contrast, Ron Howard last year stole a march on Alan G. Parker, maker of this new film, by having – with the help of producer George Martin’s son Giles and presumably Apple – original live sound in Eight Days A Week, about the touring years, as well as new spoken contributions from McCartney and Starr. Neither appears in It Was Years Fifty Ago Today! Who does?

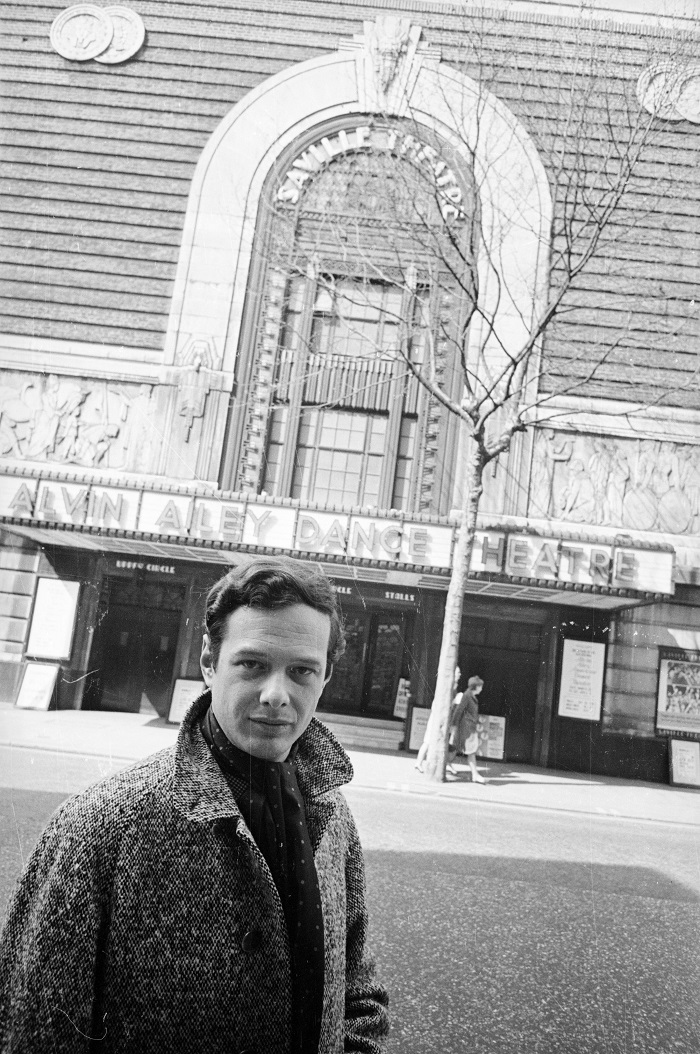

The four themselves, of course, in black and white, from various clips amassing from 1963 in the form of cheeky and, increasingly in 1966, combative press conferences. Many of these can be found on YouTube. One of the more intensive periods of defence-before-the-press was as they headed for the last-ever tour, of America in August 1966. Lennon had set the fires blazing in the Bible Belt by a casual comparison to Christ and the Beatles being more popular… It was really the turning-point in the band’s relation to their gargantuan public. After horrible experiences in the US (and, just before, in the Philippines) they vanished from view. What emerged in 1967 was a completely refashioned quartet, an utterly different sound world and, from behind closed doors, astonishingly innovative recording techniques.

This is the frame for Parker’s film: historical, cultural, anecdotal. Analysis of the Pepper music is of necessity skimpy, as the film gives us in that respect nothing to listen to. Useful and largely articulate talk comes from well-known Beatles commentators such as biographers Philip Norman and Hunter Davies and journalist Ray Connolly, and from – until now – relative unknowns such as Barbara O’Donnell, who worked for manager Brian Epstein, and Jenny Boyd, sister of Harrison’s first wife Pattie, coming across still as a cut-glass 1960s charmer. Rather sweetly, a groomed, smiling, 75-year-old Pete Best, sacked as drummer in 1962, has some screen-time to praise his three long-lost friends, though this is inessential as of course he had nothing to do with Pepper or, indeed, the recorded legacy.

This is the frame for Parker’s film: historical, cultural, anecdotal. Analysis of the Pepper music is of necessity skimpy, as the film gives us in that respect nothing to listen to. Useful and largely articulate talk comes from well-known Beatles commentators such as biographers Philip Norman and Hunter Davies and journalist Ray Connolly, and from – until now – relative unknowns such as Barbara O’Donnell, who worked for manager Brian Epstein, and Jenny Boyd, sister of Harrison’s first wife Pattie, coming across still as a cut-glass 1960s charmer. Rather sweetly, a groomed, smiling, 75-year-old Pete Best, sacked as drummer in 1962, has some screen-time to praise his three long-lost friends, though this is inessential as of course he had nothing to do with Pepper or, indeed, the recorded legacy.

Most interesting of all is ex-pop manager Simon Napier-Bell, fearsomely intelligent, who reckons he was the last person to “hear” Brian Epstein. Epstein’s death from pills and booze in August 1967 was a complicated affair, as traumatic to the four as the death threats of 1966. He, too, hadn’t had much to do with Pepper and without question was feeling sidelined. In his last days he was, if Napier-Bell remembers right, hoping to get the younger man into bed, but Napier-Bell was in Ireland (and never, anyway, going to do Epstein’s bidding). He had invented an early version of the answerphone. On his return to London he heard a succession of blurred messages from the 32-year-old, left through the evening of his death. What Napier-Bell reveals next, one of the more jolting moments in the film, would amount to a spoiler...

Two significant survivors drastically missing here are Epstein’s lieutenant Peter Brown and McCartney’s girlfriend for most of the Beatles era, Jane Asher. Both are alive and thriving, can claim to have been in the eye of the storm from 1963 and would, as interviewees, have been not just feathers in Parker’s cap but lightning-bolt scoops. Alas, they are as likely to talk as Parker was of getting even two seconds of “A Day in the Life”. But those two saw it all.

We must be content with some rare footage not of Pepper-making – that would be gold-dust – but of events early in the Apple years: glimpses of each Beatle in a world even further removed from the protective luxuries and early-form showbiz high security of the touring years. After Pepper they rocketed into, even for them, entirely untested territory of fame. The main virtue of It Was Fifty Years Ago Today! is to remind us how they shaped not only the late 1960s but, in senses more than musical, the very culture of the 20th century’s last third.

Overleaf: watch the trailer to It Was Fifty Years Ago Today!

Inversion may not be the catchiest of titles, but in the case of Iranian director Behnam Behzadi’s film its associations are multifarious. On the immediate level it refers to the “thermal inversion” that generates the smogs that engulf his location, Tehran, and also direct his story. Meteorologically, the phenomenon happens when a layer of warm air sits over one of cold, preventing it from rising, and trapping pollutants in the atmosphere.

But there’s surely a deeper relevance in this story of family conflict – in particular sibling antagonism – that relates to the position of women in Iranian society, how their assertions of independence can be easily blocked by the society (and not only by the men) that surrounds them. The stand-off in the Earth’s atmosphere compares, at least loosely, with the human oppositions that Behzadi depicts in his film.

It details the struggles to negotiate the variety of complications that life throws up

However, its opening depicts a world in which women are existing rather comfortably on their own terms. Niloofar (Sahar Dolatshahi) lives with her mother Mahin (Shirin Yazdanbakhsh): she is the youngest child, and remains unmarried, while her older brother and sister have their own families. It’s not that she looks after the older woman, who lives a busy and independent life which is curtailed only by her health problems. When the Tehran smog is heavy, Niloofar tries to prevail on her mother to stay at home; the latter insists, almost skittishly, that as long as she has her medicine and oxygen with her, all will be well.

It’s a middle-class environment that allows Niloofar to live an independent life, running the tailoring business that belonged to her late father: she has developed it over more than a decade, and has further plans for expansion. There appear to be no restrictions in her professional world and, unknown to her family, she has renewed contact with a childhood friend who has returned to Tehran from abroad, and their interaction is beginning to look like they are dating. Again, it’s a process in which Niloofar is an equal player.

When the inevitable happens, and Mahin ends up in hospital, all that looks set to change. The doctor’s prognosis is uncompromising: Mahin must leave Tehran, or the consequences will be fatal. There isn’t so much a family conclave, as a decision, without discussion, by the two married siblings that Niloofar will accompany her, leaving her life and work in Tehran behind. “No husband, no children, so I don’t count?” is her retort, as the family encounters become increasingly confrontational (not least when her brother simply shuts her out of her work premises, to pay off his own debts). The older sister sees it as no less of a transaction: in return for going with the mother, Niloofar will receive an allowance. (Sahar Dolatshahi with Ali Mosaffa, playing her brother, pictured above)

When the inevitable happens, and Mahin ends up in hospital, all that looks set to change. The doctor’s prognosis is uncompromising: Mahin must leave Tehran, or the consequences will be fatal. There isn’t so much a family conclave, as a decision, without discussion, by the two married siblings that Niloofar will accompany her, leaving her life and work in Tehran behind. “No husband, no children, so I don’t count?” is her retort, as the family encounters become increasingly confrontational (not least when her brother simply shuts her out of her work premises, to pay off his own debts). The older sister sees it as no less of a transaction: in return for going with the mother, Niloofar will receive an allowance. (Sahar Dolatshahi with Ali Mosaffa, playing her brother, pictured above)

Yet these loyalties aren’t quite so one-sided. Niloofar’s teenage niece Saba (Setareh Hosseini) implicitly takes the side of her aunt (she can see how her own future might develop). The possibilities of the burgeoning romantic attachment may be tested when certain other dependencies are revealed, but such difficulties can be negotiated (it involves a great deal of to-and-froing on the Tehran mobile network). And, as the matriarch begins to recover she reveals a keener will than anyone had anticipated.

The elements of drama are strong, and give the film’s closely observed scenes – even when a touch of melodrama slips in, Inversion is still very much a work of realism – their power. It premiered at Cannes last year in the “Un Certain Regard” programme, and the quality of the acting impresses profoundly. Dolatshahi has a paradoxical combination of composure and vulnerability, and her face captivates the camera: she’s matched by the utterly natural Hosseini, the youngest presence on the screen, as well as by the scheming siblings, unsympathetic but still somehow understandable. Such a keen definition of character more than compensates for a budget we assume was modest. (Romantic interest: Sahar Dolatshahi with Ali Reza Aghakhani, pictured above)

The elements of drama are strong, and give the film’s closely observed scenes – even when a touch of melodrama slips in, Inversion is still very much a work of realism – their power. It premiered at Cannes last year in the “Un Certain Regard” programme, and the quality of the acting impresses profoundly. Dolatshahi has a paradoxical combination of composure and vulnerability, and her face captivates the camera: she’s matched by the utterly natural Hosseini, the youngest presence on the screen, as well as by the scheming siblings, unsympathetic but still somehow understandable. Such a keen definition of character more than compensates for a budget we assume was modest. (Romantic interest: Sahar Dolatshahi with Ali Reza Aghakhani, pictured above)

Inversion doesn’t quite fit into the arthouse strand of Iranian cinema that is best known in the West (and it certainly doesn’t belong to the mainstream that dominates the country’s film industry). Possibly, at home, it falls into what's called the “popular art” genre, and its concerns – detailing the struggles to negotiate the variety of complications that life throws up – are close to those of Asghar Farhadi’s recent The Salesman. Both deal with the consequences of a settled life being disrupted. Though European realism might also be another point of reference, Behzadi’s brisk conclusion consciously leaves any such allegiance behind – in a way that feels more accomplished cinematically than it does thematically.

To say that a film opens up a world to us may seem a double-edged compliment. After all, why should we be surprised to recognise patterns of life in Tehran as somehow familiar – even if we think of Iran as “closed” in some way? Surprisingly, I’m drawn to comparisons with Jon Snow’s broadcasts for Channel 4 this week on the Iranian elections, which conveyed something, however briefly, of what life there, in all its contradictions, may be like. For almost an hour-and-a-half Inversion anchors us in Behzadi’s here-and-now. It is no small achievement.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Inversion

Guy Ritchie is back birthing turkeys. Who can remember/forget that triptych of stiffs Swept Away, Revolver and RocknRolla? Now, having redemptively bashed his CV back into shape with the assistance of Sherlock Holmes, the mockney rebel turns to another of England’s heritage icons in King Arthur: Legend of the Sword.

Do, however, dump that fantasy of yours of a triumphant return to the multiplex for medieval chivalry and courtly romance. Messrs Malory, Tennyson and dear old Lancelyn-Green can start rotating in their tombs now because King Arthur is basically Lock, Stock and One Stonking Sword, in which Ritchie filters national myth through the only aesthetic he knows: the stop-start gor-blimey rock video in which everyone channels their inner Winstone. We begin at max. vol. in Camelot, a bristling castle deep in the digitised heart of soundstageland where Uther Pendragon (Eric Bana) is ousted by his black-hearted sibling Vortigern (Jude Law), but not before sending his infant son off to float in a boat down-river to Londinium, where absolutely no one speaks Latin. Here the boy is adopted by a brothel, studies at the school of knocks and knockers before eventually growing up to assume the guise of Charlie Hunnam.

We begin at max. vol. in Camelot, a bristling castle deep in the digitised heart of soundstageland where Uther Pendragon (Eric Bana) is ousted by his black-hearted sibling Vortigern (Jude Law), but not before sending his infant son off to float in a boat down-river to Londinium, where absolutely no one speaks Latin. Here the boy is adopted by a brothel, studies at the school of knocks and knockers before eventually growing up to assume the guise of Charlie Hunnam.

Who, you may perhaps wonder, the hell is Charlie Hunnam? And where’s Elba, McAvoy or, sod it, Hiddleston when you want a screen hero to beg a selfie with at the prem? “Get me Hunnam” were not the words uttered by whoever was in charge at Warner Bros when the casting merry-go-round started six years ago. But on the first day of production he was the last man still in the vertical and to his credit he certainly looks the part. Whenever he takes off his car coat, that torso is a rubbly cluster of chamfered boulders scarcely contained within a plucked Tinseltown dermis. It’s only when he opens his mouth to declaim the script’s deathless poetry that you think, maybe don’t.

To be fair, that goes for everyone else in King Arthur: Legend of the Sword. Arfur falls in with a lairy cohort on secondment from the Two Smoking Barrels visitor experience. They're lads called Arthurian things like Goosefat Bill, Wet Stick, Mischief John. You can randomly generate these idiot names. Bob Cobblers, Perry Pliars, Def Geoffrey, Burkina Fatso, Sid Skidmark, Kung Fu Trev, “The Jizza”, Handjob Hannan, Strong and Stable Nige, David Beckham (yes he’s actually in it, pictured: Vinnie Jones can sleep easy).

To be fair, that goes for everyone else in King Arthur: Legend of the Sword. Arfur falls in with a lairy cohort on secondment from the Two Smoking Barrels visitor experience. They're lads called Arthurian things like Goosefat Bill, Wet Stick, Mischief John. You can randomly generate these idiot names. Bob Cobblers, Perry Pliars, Def Geoffrey, Burkina Fatso, Sid Skidmark, Kung Fu Trev, “The Jizza”, Handjob Hannan, Strong and Stable Nige, David Beckham (yes he’s actually in it, pictured: Vinnie Jones can sleep easy).

Meanwhile back at CGIamelot, whither Arfur must journey to draw a sword from a stone and thusly provoke avuncular wrath, Jude Law is holding the fort with just two scowling sidekicks and a thousand-strong army of pixellated stickmen (pictured above). The problem with Jude, whose task is to commit nephewcide so he can assume the powers of Excalibur, is that he’s just not dastardly enough, however much he does that wicked thing with his neck or slumps bolshily in his throne or knifes his loved ones, therein depleting the screen of its last but one speaking female. The only woman who gets to say much at all is called The Mage, which feels like a covert misspelling of Madge to whom Ritchie was once espoused. The Mage (Astrid Bergès-Frisbey, pictured below) has lighty-uppy eyes and telekinetic control over various fauna which make sundry plot interventions when the script can’t think how else to get Arfur and co out of yet another slap (and tickle: pickle).

Action comedy is the trickiest of hybrids. Ritchie goes at it with a unfit-for-purpose toolkit of mallets, ping-pong bats and one phallusy broadsword. When the script’s not being clever-clever or funny-funny it’s being stupid-stupid. Enormo-pachyderms, one jumbo basilisk and a three-headed lady octopus all continue cinema’s galloping mania for gigantism (see also Kong: Skull Island and Jurassic World). The plot, meanwhile, is a botched origami.

Action comedy is the trickiest of hybrids. Ritchie goes at it with a unfit-for-purpose toolkit of mallets, ping-pong bats and one phallusy broadsword. When the script’s not being clever-clever or funny-funny it’s being stupid-stupid. Enormo-pachyderms, one jumbo basilisk and a three-headed lady octopus all continue cinema’s galloping mania for gigantism (see also Kong: Skull Island and Jurassic World). The plot, meanwhile, is a botched origami.

The industry press is full of theories about the film’s calamitous opening weekend. One factor no one’s mentioned is Brexit. “You are addressing England!” Hunnam intones to a top-knotted delegation of Vikings at the end. Never mind that the best bits are filmed among rocky Celtic outcrops, the rest of the world isn’t that impressed by England these days, and maybe wants no truck with its self-vaunting myths, whether rebooted, mashed up or slapped inside sniggersome inverted commas. Ritchie’s Arthurian ledge has stripped itself of all context. Even the king's famous furniture is subjected to his belittling gift for bathos. “Wossat?” says one of the rainbow nation of newly ennobled knights in a final reveal. “It’s a table,” says Arfur. “You sit at it.” This will be the only sitting.

Overleaf: it's approximately this bad

It's the church wot done it! That's the unexceptional takeaway proffered by Jim Sheridan's first Irish film in 20 years, which is to say ever since the director of My Left Foot and The Boxer hit the big time. But despite a starry and often glamorous cast featuring Vanessa Redgrave (in prime form), Rooney Mara, Theo James, and Poldark's Aidan Turner, Sheridan's adaptation of Sebastian Barry's Man Booker-shortlisted novel begins portentously and spirals downwards from there.

There's limited fun to be had from watching Mara and Redgrave play two generations of the same unfortunate woman, Rose, who has been sequestered away in an asylum for more than a half-century. But Sheridan's script, co-written with Johnny Ferguson, and the thudding overinsistence of the direction soon make a spectator feel scarcely less incarcerated. If you've seen the Judi Dench vehicle Philomena or Peter Mullan's wonderful The Magdalene Sisters, you've been round this block before, and without lines like, "I can't imagine what it would be like to be locked up for 50 years". Wanna bet?  The central question is whether or not young Rose killed her newborn child with a rock, an act of infanticide which Mara denies early on as piano chords come crashing down around her. Her ageing, shining-eyed self hoves into view in the form of a gravely arresting Redgrave (pictured above) who, it turns out, herself plays a mean piano. Alas, it seems that Rose will soon have to find fresh musical environs given that the mental health hospital to which she has been confined is being turned into a spa hotel. (Frankly, I would just ask to stay on.) At which point, cue a strapping psychologist (Eric Bana) on hand to reassess Rose and to peruse the diaries that allow for the parallel structure that ensues. Guess what: he likes Beethoven, too.

The central question is whether or not young Rose killed her newborn child with a rock, an act of infanticide which Mara denies early on as piano chords come crashing down around her. Her ageing, shining-eyed self hoves into view in the form of a gravely arresting Redgrave (pictured above) who, it turns out, herself plays a mean piano. Alas, it seems that Rose will soon have to find fresh musical environs given that the mental health hospital to which she has been confined is being turned into a spa hotel. (Frankly, I would just ask to stay on.) At which point, cue a strapping psychologist (Eric Bana) on hand to reassess Rose and to peruse the diaries that allow for the parallel structure that ensues. Guess what: he likes Beethoven, too.

Rose's youth, it seems, consisted of parrying or at least juggling the advances of a motley crew of suitors, played by an array of modern-day celluloid "it boys", among them Theo James and a largely sidelined Aidan Turner. While an implacable Mara suggests a waitress wanting merely to get on with her business, these men have other ideas, though quite how James (pictured right with Jack Reynor) references being "a priest who wants to be a man" while keeping a straight face is an achievement worth pondering. In any case, gossipy, small-town village life bodes ill for the romance that develops between Rose and an RAF pilot, Michael (Reynor), whose arrival sets the cat among the politically riven pigeons. Small wonder that the Book of Job gets an onscreen workout, the so-called "secret scripture" of the title.

Rose's youth, it seems, consisted of parrying or at least juggling the advances of a motley crew of suitors, played by an array of modern-day celluloid "it boys", among them Theo James and a largely sidelined Aidan Turner. While an implacable Mara suggests a waitress wanting merely to get on with her business, these men have other ideas, though quite how James (pictured right with Jack Reynor) references being "a priest who wants to be a man" while keeping a straight face is an achievement worth pondering. In any case, gossipy, small-town village life bodes ill for the romance that develops between Rose and an RAF pilot, Michael (Reynor), whose arrival sets the cat among the politically riven pigeons. Small wonder that the Book of Job gets an onscreen workout, the so-called "secret scripture" of the title.

"My memories, my memories, they took my memories," bleats the senior Rose, who drifts in and out of lucidity and sedation and whom Redgrave invests with the singular intensity that has long been her signature. This ageless actress (who turned 80 in January) has for some while been scooping up films like Atonement and Foxcatcher and running with them. Sheridan grants her far more screen time than those two did, but it's a lost cause. As Bana's shrink presses Redgrave's furtive, fretful Rose for details about a life glimpsed in increasingly lurid fragments, you're tempted to wish all involved had abandoned the script and allowed a venerated performer to reflect on the many and happier acting opportunities that surely constitute her memories, and ours.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for The Secret Scripture

François Ozon’s Frantz is an exquisitely sad film, its crisp black and white cinematography shot through with mourning. The French director, in a work where the main language is German, engages with the aftermath of World War One, and the moment when the returning rhythms of life only emphasise what has been lost. The eponymous hero of his film is one of its casualties – we see Frantz only in flashbacks – and his death has left a gaping, if largely unarticulated wound. His erstwhile fiancée Anna (Paula Beer, a revelation) has become effectively his widow, living with Frantz’s parents. That element of company assuages both their grief and her own, but it’s a world in which the shutters have been drawn down, both literally and symbolically.

It’s an unusually subdued mood for Ozon, a prolific director accomplished across genres (Under the Sand, all the way back in 2000, was the last time he assayed such sombre territory). He works around the story of a 1932 film by Ernst Lubitsch, Broken Lullaby, itself adapted from a stage play by the French writer Maurice Rostand, although the transformations Ozon makes, especially in the second half, finally count for more than anything that he has borrowed. If terming the film “exquisite” implies a level of artifice, there is certainly an element of mannerism. Ozon’s subject is less grief itself than the secrets and lies that come to surround it: how we keep secrets to guard the feelings of others, and how such acts of apparent kindness easily shade into something profoundly damaging.

They are no longer defined through the memories of a dead man

The film’s opening scenes elegaically capture life in the quiet provincial German town where Anna’s existence revolves around her daily visits to Frantz’s grave (which is itself a fiction: his body, of course, never came back from the front). Her discovery that someone else is leaving flowers there leads to acquaintance with Adrien (Pierre Niney), the Frenchman who has come, he says, to remember the German friend he had known in Paris before the war. After uncompromising rejection by Frantz’s stern doctor father – “Every Frenchman is my son’s murderer,” he insists initially – the young man is gradually welcomed in by the family. His memories, of visits to the Louvre with Frantz, and their companionship in music (both are violinists), come to make his presence restorative for all (pictured below).

Ozon draws beautifully restrained playing from Ernst Stoetzner as Frantz’s father, and Marie Gruber as his mother; they are figures from an older, stricter generation, which only makes the sense of their feelings beginning to thaw more touching. As her world changes, Anna, who at the film’s opening has rejected the attentions of a well-meaning suitor offering companionship rather than love, finds prospects opening before her in a way she would never have imagined possible. As she walks with Adrien in the countryside, they talk – both are lovers of poetry, Verlaine a shared favourite – and gradually establish a bond that is their own; they are no longer defined through the memories of a dead man. But such foundations for any possible future will not withstand life’s harsher truths. Revealing them would be impossible, since Ozon is himself a storyteller who here, especially, plays with our expectations. He confounds (for those who know themes from the rest of his work) some of those on one level, and allows the visual reality of his film to flesh out a story that is itself illusory. Anna’s complicity in maintaining that version of events precipitates her journey to France in the second half (at which point Ozon leaves Lubitsch behind).

But such foundations for any possible future will not withstand life’s harsher truths. Revealing them would be impossible, since Ozon is himself a storyteller who here, especially, plays with our expectations. He confounds (for those who know themes from the rest of his work) some of those on one level, and allows the visual reality of his film to flesh out a story that is itself illusory. Anna’s complicity in maintaining that version of events precipitates her journey to France in the second half (at which point Ozon leaves Lubitsch behind).

There she begins to function as a fully independent character, dealing with a world far wider than the one from which she has come; she asserts her ability to engage with it on her own terms, however unexpected or cruel it proves. Rediscovering Adrien, we are left with a sense that war’s casualties include those who have survived the physical hell of the trenches no less than those whose lives ended there.

Paula Beer conveys the trajectory of Anna’s journey wonderfully, her character’s initial reticence gradually opening out to reveal reserves of inner strength. She conveys the unspoken gradations of feeling with a rare, subtle power, in a way comparable to Ozon’s use of colour. The black and white images of Frantz give the film its opening severity, but in fact Ozon and his cinematographer Pascal Marti vary that texture, allowing elements of distant, subdued colour to intrude and change the mood.

The effect is sometimes that we are witnessing life returning, however hesitatingly, to this dead landscape. Yet the colour is also there, paradoxically, in the film’s scenes of invention, when cinema is doing what is most natural to it, telling a story – but in this case, too, inventing a false narrative. The final scene has Anna in the Louvre, looking at Manet’s Le suicide. “It makes me want to live,” we hear her say. What a nuanced journey she has accomplished, how impressively shaded Beer’s performance. Ozon has achieved emotional depths that are rather new for him.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Frantz

For a demoralising period towards the start of Miss Sloane, it looks as if we’re in for a high-octane thriller about palm oil. That’s right, palm oil. Everything you never wanted to know about the ethics and economics of the palm oil market is splurged in frenetic, rat-a-tat, overlapping, school-of-Sorkin dialogue. After 10 minutes your ears need a rest on a park bench.

When Ridley Scott returned to his hideous intergalactic monster with Prometheus five years ago, he brought with him a new panoramic vision encompassing infinite space, several millennia of time and the entire history of human existence. With Alien: Covenant, he makes a more modest proposal.

To appreciate the full engaging silliness of Mindhorn, it helps to have been born no later than 1980. Those of the requisite vintage will have encountered the lame primetime pap it both salutes and satirises. Everyone else coming to this spoof will just have to take it on trust that things, admittedly not all of them British, were indeed this bad back in the day.

The eponymous detective of the adventure crime show wears a brown leather blouson, grey leather slip-ons and an eyepatch that allows him to see the truth. He’s a hot smoothie who hunts down bad guys alone, principally on the Isle of Man, with the help of a fast soft-top and some arthritic moves from the martial arts playbook. But that was the Eighties and now Richard Thorncroft, the actor who played him, is a balding tub of lard in a bedsit reduced to earning a crust endorsing surgical supports for the elderly. His agent has no work for him. He gets summoned to an audition to play a yardie as a result of a clerical error. Kenneth Branagh, one of several A listers recruited to play himself, is underwhelmed.

T hen a murder is committed on Detective Mindhorn’s old stomping ground and there’s only one person the presumed culprit (Russell Tovey) will communicate with. Thorncroft imagines this is an opportunity that can put him back in the game. Cue a frantic caper which mimics precisely the kind of naff storylines Mindhorn got mixed up in all those decades ago.

hen a murder is committed on Detective Mindhorn’s old stomping ground and there’s only one person the presumed culprit (Russell Tovey) will communicate with. Thorncroft imagines this is an opportunity that can put him back in the game. Cue a frantic caper which mimics precisely the kind of naff storylines Mindhorn got mixed up in all those decades ago.

The pleasure of this low-budget British comedy is very much centred on the charming, buffoonish performance of Julian Barratt, the funny one from The Mighty Boosh, as a washed-up old ham whose ego has somehow kept his estimation of himself intact. (See also Bill Nighy in Their Finest.) There is almost no delusion which doesn’t have Thorncroft in its grip. Chief among these is that his old lover and co-star Patricia Deville (Essie Davis) still has the hots for him. Humiliatingly she has married Thorncroft’s thinner Dutch stuntman Clive (played by Barrett’s co-scriptwriter Simon Farnaby, pictured above).

Loitering on the fringes are Andrea Riseborough as a policewoman, Nicholas Farrell as a villainous civic leader, Richard McCabe as a hollowed-out cokehead in a caravan, and Steve Coogan (looking freakishly thin and ripped) as Thorncroft’s creepy old supporting player. Mindhorn is directed by Sean Foley, tacking across from stage comedy and bringing in pals like Branagh to lighten up and have a good time.

Loitering on the fringes are Andrea Riseborough as a policewoman, Nicholas Farrell as a villainous civic leader, Richard McCabe as a hollowed-out cokehead in a caravan, and Steve Coogan (looking freakishly thin and ripped) as Thorncroft’s creepy old supporting player. Mindhorn is directed by Sean Foley, tacking across from stage comedy and bringing in pals like Branagh to lighten up and have a good time.

There are fun setpieces including a crap parade with a real shoot-out, plus some lovely lines too. Harriet Walter, ditching Thorncroft as her client, has a killer putdown which she administers over the phone: “I’ve left your headshots in reception.” It won’t win many awards or break many box office records, but Mindhorn doesn’t outstay its welcome and approaches the important business of spoofery with a practically academic attention to ridiculous detail. A hoot.

Overleaf: watch the trailer to Mindhorn

The original Guardians of the Galaxy from 2014 had a freshness to its humour and introduced audiences to a set of novel characters; unfortunately, the sequel is overstuffed with ageing movie stars trying to get a slice of the action. There’s always a camp knowingness about Marvel scripts, it's one of the studio's charms, but here the overt cynicism begins to drag with lines like "We’re really going to be able to jack up our price if we’re two-times galaxy saviours".

Foul-tempered Rocket the raccoon and two of the new characters are very welcome on screen – there's cute baby Groot who just wants to dance and Mantis (Pom Klementieff), a naive "Empath" who is adorned with antennae that sense everyone’s emotions. She makes an excellent comic foil for muscle man Drax (Dave Bautista) and definitely adds to the film's eclectic characters. But the old-time stars drafted in – Kurt Russell, Sylvester Stallone, David Hasselhoff – add little to this intergalactic party, other than queasiness watching their weirdly plasticky faces.

Crash cut to 34 years later on a planet far, far away...

Guardians of the Galaxy Vol 2 opens with one of those scenes where an older actor is recreated as their youthful self through the wonders of CGI – think Carrie Fisher in Rogue One: A Star War's Story. Here it’s Kurt Russell making the audience suffer the uncanny valley effect. He plays an out-of-town hunk with a flowing ‘70s hairdo, impregnating an innocent Missouri teenager in 1980. Crash cut to 34 years later on a planet far, far away, where Peter Quill (Chris Pratt) and his motley crew of Guardians are battling a giant squid with too many teeth while baby Groot boogies to ELO’s Mr Blue Sky – all this before the main titles.

The first movie was all about establishing the identities of these misfit space vagabonds, eavesdropping on their quarrelsome banter and enjoying their video-game inspired violence, set to a kitschy but infectious MOR soundtrack. But we know these characters now, and the sequel’s plot is bogged down in tedious family drama dynamics – Quill's quest for his mysterious dad (shades of Luke Skywalker/Darth Vader) and the rivalry between sisters Gamora (Zoe Saldana) and Nebula (Karen Gillan).

The movie stop-starts between fight-chase sequences played out against pop tunes from Quill’s beloved mix-tape; there's something a little alienating about the repeated use of dissonance between the cheery songs ("Come a Little Bit Closer" by Jay & The Americans) and the slomo violence meted out by the Guardians. The disjunction continues with dialogue scenes that flit between gags about turds, Cheers and douchebags and soppy/profound stuff about the true nature of fatherhood and friendship.

The movie stop-starts between fight-chase sequences played out against pop tunes from Quill’s beloved mix-tape; there's something a little alienating about the repeated use of dissonance between the cheery songs ("Come a Little Bit Closer" by Jay & The Americans) and the slomo violence meted out by the Guardians. The disjunction continues with dialogue scenes that flit between gags about turds, Cheers and douchebags and soppy/profound stuff about the true nature of fatherhood and friendship.

The art directors seem to have mined a mash-up of Roger Dean and Hipgnosis album covers for the overall look of the film, while the make-up artists' heavy-handed maquillage have rendered all but Pratt and Russell unrecognisable from their real-life selves. Elizabeth Debicki (pictured above), who exposed so much of her own skin in the designer dresses of The Night Manager, is completely coated in gold paint, while Michael Rooker’s Yondu is rendered Smurf blue with dodgy dentition and a detachable Mohican. His character, a quasi-father figure, gets more than his fair share of screen time. Fans will be rewarded with not one but two jokey cameos by Stan Lee and Howard the Duck; sitting through the end credits results in no less than five teaser trailers. It's hard though to warmly recommend the film to non-fans due to too many in-jokes and a general sense of complacency in script and direction. It’s simply not as much fun as the first film because it's a reprise rather than a reinvention.

Overleaf: watch the official trailer for Guardians of the Galaxy Vol 2