ReMastered: Devil at the Crossroads, Netflix review - a story well told but marred by clichéd style | reviews, news & interviews

ReMastered: Devil at the Crossroads, Netflix review - a story well told but marred by clichéd style

ReMastered: Devil at the Crossroads, Netflix review - a story well told but marred by clichéd style

Robert Johnson: a pact with the devil? A myth de-constructed, yet enhanced

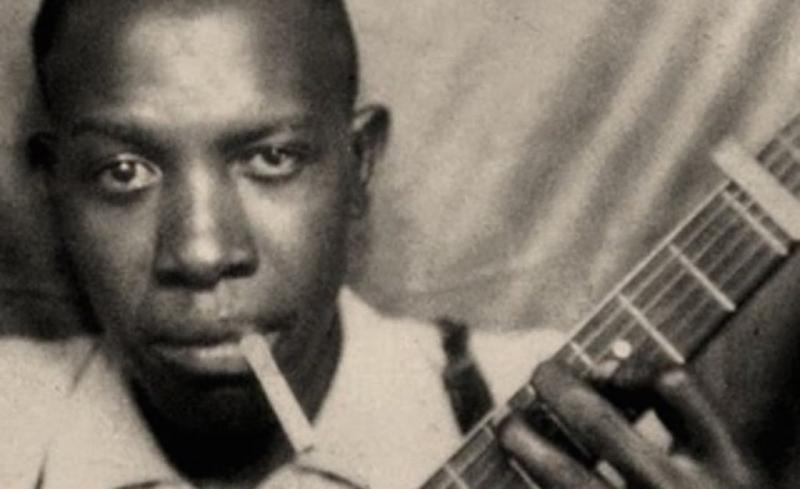

Mississippi bluesman Robert Johnson’s reputation was much enhanced by the story – never substantiated – that he’d met with the devil one night at a crossroads, and was miraculously taught exquisite guitar licks that astounded his juke-joint audiences and later the world.

There’s been much mythologising about Johnson, and in recent years, a vogue for deconstructing the myth: Johnson was talented, but he was just one of many extraordinarily inspired and gifted musicians – Willie Brown, Tommy Johnson, Son House, Blind Willie Johnson, Skip James, Blind Lemon Jefferson, to name just a few – who managed to transform the experience of sharecropping, poverty, racism and a culture of lynching into an art form of great sophistication.

This documentary, directed by Brian Oakes, relies mostly on musician, researcher and Johnson expert Bruce Conforth, and treaded a well-balanced path between fact and myth. When Johnson first came to general public attention in the 1960s with the release of the album Robert Johnson: King of the Delta Blues, several of his contemporaries, including Bukka White, Skip James, Mississippi John Hurt and Son House had recently been “found” still alive by blues enthusiasts. They had stories – some of them no doubt tall – to tell, but Johnson, who had a complex and virtuosic guitar-picking style of his own, a mournful tenor and sometimes falsetto voice, and poetic lyrics that spoke of sex and death, remained something of an unknown legend, with an aura of mystery around a man who had met his death unnaturally early.

Today, we know a great deal more about Robert Johnson, and the documentary reflected this increase in knowledge very well. The story is well told – by Conforth, two Johnson grandsons and other musicians with first or second-hand knowledge of the blues legend. We discovered that, rather than being taught by the devil, Johnson learned his guitar from bluesman Ike Zimmerman, a virtuoso who was never recorded. There were also some articulate historians and musicians who gave a very good account of the context: the terrible racism of the Deep South, the difficult peripatetic life of a musician playing what was regarded as the “devil’s music”, the often violent and drunken world of the juke-joint, where the bluesmen played for dances and women went to hang out with wild men, and the web of beliefs and practices around traditional sorcery and healing, the "hoodoo" to which Robert Johnson referred in his songs.

Today, we know a great deal more about Robert Johnson, and the documentary reflected this increase in knowledge very well. The story is well told – by Conforth, two Johnson grandsons and other musicians with first or second-hand knowledge of the blues legend. We discovered that, rather than being taught by the devil, Johnson learned his guitar from bluesman Ike Zimmerman, a virtuoso who was never recorded. There were also some articulate historians and musicians who gave a very good account of the context: the terrible racism of the Deep South, the difficult peripatetic life of a musician playing what was regarded as the “devil’s music”, the often violent and drunken world of the juke-joint, where the bluesmen played for dances and women went to hang out with wild men, and the web of beliefs and practices around traditional sorcery and healing, the "hoodoo" to which Robert Johnson referred in his songs.

Conforth put forward a very credible thesis: like the tragic yet super-talented rock musicians who form part of the 27 Club (Joplin, Winehouse, Morrison, Cobain and Hendrix), dying prematurely from drug or drink excess. Conforth reiterated the notion that such almost supernatural talent came with a price – the idea of a pact with the devil serving as a useful metaphor for this paradox. Johnson was both a little crazy, and driven outside and beyond the realm of an everyday life that could be sustained. It was a new take on Robert Johnson, and a very appealing one. It goes some way to explaining, in an original way, why he might have achieved a mythical status found again with those later martyrs – gifted yet damned – of rock'n'roll excess.

The film would not be complete without enthusiastic and reverential contributions from Keith Richards, Eric Clapton and John Hammond. And yet, for all these pluses, the subject was let down by an over-fussy visual style, with clichéd and over-dramatic shots of a faceless blues man, and animation that’s supposed to be evocative or help tell a story, but more often than not painfully literal. Such stylistic crutches unfortunately played to the myth that other parts of the documentary managed so well to deconstruct.

Various musicians delivered their versions of Johnson’s blues, but either as relatively soulless note-for-note copies, or in a more creative way that failed to communicate the intense minimalism of the originals. Myth-busting aside, Robert Johnson was an extraordinary musician, in a class of his own. Sadly, the film, for all its efforts, fell short of demonstrating this in a way that should have taken the breath away. There was a brief live clip of Mick Jagger singing “Love in Vain”, one of Johnson’s many masterpieces: to his credit, and he's a man of taste, he isn’t trying to be Robert Johnson. For those few seconds he taps into something of Johnson's cliff-edge emotion, gut-wrenching despair and tantalising eroticism, qualities never quite expressed in the film, but essential to the greatness of this outstanding creative talent and entertainer.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment