Richard Thompson has been stretching boundaries and defying expectations for almost half a century. An unassuming 63-year-old with a neat beard whose sole concession to showbiz is his jaunty black beret, though nominally a folk artist Thompson remains doggedly unaffiliated to any scene, trend or ethos.

While still a teenager, with Fairport Convention Thompson was instrumental in concocting an organic blend of folk and rock. With his first wife, Linda, he plumbed the emotional depths of confessional singer-songwriting while also writing rude songs about licking lollipops. He has since scored films for Werner Herzog, made instrumental albums combining music from North Africa with Duke Ellington's "Rockin' in Rhythm", and written an extended piece of musical narrative scored for a chamber orchestra.

His music taps into vaudeville, classical and Tin Pan Alley. His One Thousand Years of Popular Music show travels from 13th-century smash hit “Sumer Is Icumen In” to Britney's “Oops, I Did It Again” via Henry Purcell, Gilbert and Sullivan, Hoagy Carmichael, Abba and Prince. In 2010 he curated the Meltdown festival at the Southbank. An endlessly inventive guitarist, he favours Arabic and African scales – and Celtic drones – over blues notes.

His music taps into vaudeville, classical and Tin Pan Alley. His One Thousand Years of Popular Music show travels from 13th-century smash hit “Sumer Is Icumen In” to Britney's “Oops, I Did It Again” via Henry Purcell, Gilbert and Sullivan, Hoagy Carmichael, Abba and Prince. In 2010 he curated the Meltdown festival at the Southbank. An endlessly inventive guitarist, he favours Arabic and African scales – and Celtic drones – over blues notes.

He may look like the quintessential suburban Englishman, but looks can be deceiving. Thompson has now lived in Los Angeles for nearly half his life. Once a devotee of Sufism, he remains a practising Muslim. In recent years he has become the capo of a growing musical dynasty. Son Teddy and daughter Kami from his marriage to Linda are both musicians. His youngest son from his second marriage is at university but shaping up to be a mean bass player, and then there’s “a grandson who will probably end up as a musician very soon. He’s very talented. It’s always great to play with them all, and to see them perform as well. It’s just the way it should be.”

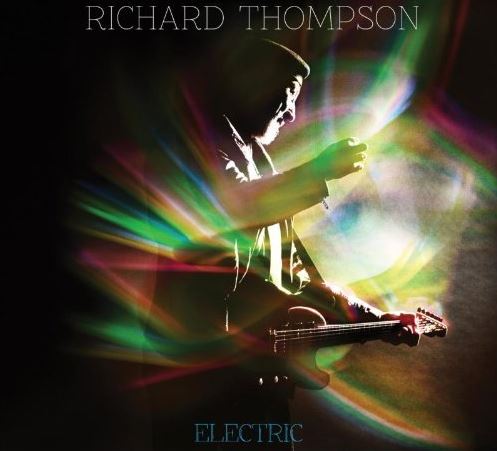

Serious, with flashes of dry humour, Thompson thinks deeply about music, its function in society, and both how and why it impacts on artist and audience. His latest album, Electric, was recorded in Nashville with Buddy Miller. It almost goes without saying that it is superb. He spoke to theartsdesk on one of his regular trips back to London.

GRAEME THOMSON: Electric is quite a loaded title, but also slightly misleading. The album rocks hard yet it also has some of your most poignant moments.

RICHARD THOMPSON: You’re assuming it was my title! It’s not really my title, it was a record company title. That’s OK, that’s fine. I usually get to choose my own titles but they said they had this great idea, we can do great things with this title, so I said, "Off you go." It’s some sort of strange, bizarre marketing exercise. I’m sure in weeks to come it will all become clear...

Given the state of the industry these days, do you ever question the value of making albums?

I like records, I like album-length CDs. I like collections of songs, just like I like collections of poems. I like things assembled in digestible chunks rather than a couple of tracks downloaded. I’m always trying to make an album that hangs together and is appealing. I’m just addicted to an old format. I think it’s worked before and – hey! - it could work again...

How much forethought goes into planning an album?

How much forethought goes into planning an album?

There are different ways of doing it. I’ll take it any way it comes. Sometimes it’s just the latest pile of songs you happen to have. In this case I wrote all these songs in just a couple of months, because I wanted to do a record as a folk-power trio. We’d been doing some shows as a three-piece and I thought it was an interesting format: so perhaps I should write some things specifically for this so we can stretch it and see what we could do. I mean, at some point you just write a song, but the idea here was specifically to do a trio record and in terms of arrangements I was always thinking of the three amigos. We recorded as a trio and then we might add a rhythm guitar or a texture here and there – and we were recording in the house of a famous guitar player [Buddy Miller], so I thought he could add some guitar here and there. But it was minimal additions. I hope it sounds spontaneous, because it really was. We cut 16 tracks in four days, which is stupidly quick. We had rehearsed a couple of days beforehand, and having really great musicians helps, too. We have been playing together enough now that we know each other’s disgusting habits and that helps to streamline things.

Having self-produced the last few records it was probably time for a change, and I thought working with Buddy would be the most interesting. I knew him but I hadn’t been in the studio with him. I listened to the records he had done with Solomon Burke, Shawn Colvin and Robert Plant and thought that was the kind of sound I wanted: slightly garagey, a record that sounds like it has been recorded in a house. Funny that! We had to schlep our equipment all the way to Nashville, which was a bit of a pain, but it was really fun. He’s a really good musician and producer, and he tends to leave his ego at home – oh hang on, he was at home. He tends to leave his ego... in the shed, and whatever a track requires he will bring that. He’s very flexible and has a good pair of ears.

In terms of your writing, do you go through lean spells?

I’m always trying to write stuff. More and more I tend to write in bursts. I used to be more steady. Now I tend to think of an interesting project and I get rolling with something in mind. And other stuff trickles in when you’re doing that that don’t fit into any category. They get set aside to see if they might fit somewhere. There is at least a 50 percent disposal rate, of things that get started and either don’t get finished or just don’t make the cut. But you can always use them for spare parts, take a bridge you liked and stick it in another song. Frankenstein your music. Tchaikovsky was doing that all the time - a good idea is a good idea.

It’s a really healthy thing when the traditional get closer to the mainstream

Do you still practise? If so, what do you do?

Oh yes I do. As a guitar player I try and play as much as possible – a few hours a day if I can. It’s fun, and apart from just keeping your fingers moving and your calluses thick, you have to be exploring. I’ll hear things and try to work out how to play it. It might be something on another instrument, for instance, like an interesting chord on the piano, and you try to find a way to voice that on guitar. Or you might hear a singer singing a phrase and you think, How could I do that on guitar? Maybe by bending notes. Or you hear a piece of classical music and you think, How can I play that harmonic idea on the guitar? Or you’re writing a song and you’re thinking about tunings, keys, the accompaniment – things like that.

The female voice has been a significant thread throughout your career, from Sandy Denny, Linda Thompson and Judith Owen to, on this record, Alison Krauss and Siobhan Maher Kennedy. What draws you to that sound?

I really like female voices. I’m a baritone so it’s nice to have a higher voice - just sonically in the mix, it sits nicely. And there is an emotion to women’s voices that is just wonderful. On this album I asked Buddy if he knew any singers in Nashville who don’t twang, who don’t sound like they’ve just stepped out of the hills. He said, "There is Siobhan, who is basically Irish-English." She was great and she sang most of the harmony. Then just as were leaving town Buddy said, "Do you fancy putting Alison on this track?" I said, "It's a great idea, but I’m going to have to trust you because I'm leaving town, so just do it and if it works that’s great." So it works and it’s great.

Watch Richard and Linda Thompson singing "A Heart Needs a Home" in 1975

Why no twang?

It’s just not appropriate for the music. I didn’t go to Nashville to make a Nashville record. I went to sit in a house! My music is too English, or British, to have too much twang there. There is a little bit, inevitably, if you’re in Nashville – some of the fiddle is a little bit countrified, but on the whole I like British singers.

That sense of Britishness is still key to what you do. Even though you’ve lived in Santa Monica for three decades, you would never know it from your music.

I’m less influenced by what I consider the outside stuff – where I physically am. I’m more concerned with this inner landscape of where the drama happens. I like that landscape as a setting for songs. I always picture some windswept moor somewhere as the setting for the characters, or a grey suburb... sometimes it’s the 1950s or the 1960s, as well. That’s what you imagine in your mind as the songs are coming together. I like the cadences of British speech: the things you hear on the street in Glasgow or London or Liverpool, and they tend to sneak into songs. As a writer you create this landscape and there’s not much you can do about that. You are kind of stuck with it. I can make a real effort and make a Beach Boys type song, but maybe I won’t bother.

These days physical proximity is less of a factor, things that are far can seem really near. Certainly in terms of culture I really keep in touch with the UK very easily. I have Radio 4 on my laptop and I read the English papers online, I’m up to date with news and politics. If you live away from a place you see it more in perspective, you have it at arm's length and you see how it relates to the rest of the world and what it really means. Whereas if you’re immersed in a culture sometimes you don’t quite get it. Being away a lot and then coming back helps me to understand the culture I come from and also who I am, and also who my parents were, who my grandparents were. It all helps to put the picture together. A lot of songwriting is trying to answer those questions: who am I? Where do I come from? How come my parents were the way they were?

These days physical proximity is less of a factor, things that are far can seem really near. Certainly in terms of culture I really keep in touch with the UK very easily. I have Radio 4 on my laptop and I read the English papers online, I’m up to date with news and politics. If you live away from a place you see it more in perspective, you have it at arm's length and you see how it relates to the rest of the world and what it really means. Whereas if you’re immersed in a culture sometimes you don’t quite get it. Being away a lot and then coming back helps me to understand the culture I come from and also who I am, and also who my parents were, who my grandparents were. It all helps to put the picture together. A lot of songwriting is trying to answer those questions: who am I? Where do I come from? How come my parents were the way they were?

Would you call yourself a political writer?

There were a couple of political songs on the last record, but I tend to shy away. I think they tend to work better when they are a bit more subtle. If you use the analogy of a personal relationship to describe a political relationship, I think sometimes that’s stronger and you have a song that lasts longer. Of course, other times you have to stand up and be counted: "Out despots, now!" The song has to be like a placard in a street. There is a time and a place for that.

We are living through something of a folk revival in various permutations. Does that please you?

It’s great, it’s a really healthy thing when the traditional get closer to the mainstream. It goes in cycles. I’m always really thrilled to see younger people take an interest in tradition. It satisfies something very deep, there is a resonance to that music. Once you start singing the older songs it really does something to you that you don’t forget. Singing something that is hundreds of years old is an extraordinary thing, it echoes through the centuries and is very fulfilling. It gives you a kind of cross-reference, it almost tells you where you are on earth and what your culture is and what the possibilities are. It’s like the roots of where you are. I’ve always liked those kind of songs. I grew up on those old, dark Border ballads. As a kid my father had them up on the book shelf and I would read them on a Sunday afternoon. I used to enjoy them, but it’s fairly bleak and dark – there’s a lot of murder, a bit of incest, and a lot of magic, being carried off by the fairies and strange supernatural stuff. I think I just grew up to think that was normal. To me, pop music is this kind of fluffy stuff and traditional music is just... normal. I’m only just putting this all together now. I’d forgotten what I did as a kid, and it’s only now I really see that the roots of it go back to when I was eight, nine or 10 years old.

Watch Richard Thompson perform "Salford Sunday" from his new album Electric

Add comment