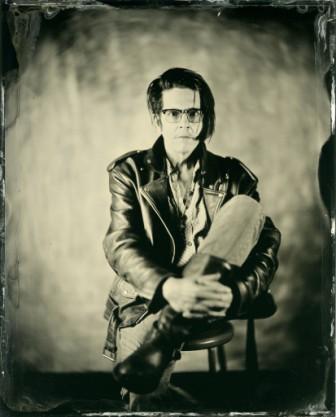

In both a personal and literary sense, Grant Hart has been to hell and back. While the 52-year-old Minnesotan is still best known as the drummer and songwriting contributor behind legendary US punk band Hüsker Dü, his fourth solo album, The Argument, is a bold adaptation of John Milton's Paradise Lost that could finally see him recognised as an artist in his own right. And it's about time.

For better or worse, Hart has spent three decades being cast as the yin to Hüsker Dü frontman Bob Mould's yang. In contrast to Mould's direct, hardcore-influenced compositions, it was Hart that brought in the band's most melodic moments, penning the likes of "She Floated Away" and "Never Talking to You Again". Unfortunately, it was also Hart that, having developed a heroin habit in the group's final years, would become the designated scapegoat post-breakup.

It's really funny having the life that I have had and then being addressed by a cop as 'sir'

After Hüsker Dü's split, the band would be name-checked as an influence on Nirvana and Pixies and songwriting rival Mould would go on to significant success, primarily with Sugar. Meanwhile Hart never received the recognition he felt he deserved, either for his significant contributions to Hüsker Dü, or for latter project Nova Mob. There were further twists of ill fate, too – among them a two year misdiagnosis with HIV and, in 2009's Hot Wax, a hard-forged solo album wiped off the map by distribution issues.

All of this explains why, as we're waiting to meet Hart in a sunny South West London pub, theartsdesk is anticipating a somewhat jaded individual. Our first impression is, rather appropriately, of a man that has seen his fair share of sin. "It's really funny having the life that I have had," he reflects at one point. "And then being addressed by a cop as 'sir'."

We're meeting to discuss the aforementioned double album, The Argument. It's an interpretation of, specifically, a treatment of Paradise Lost, dubbed Lost Paradise, written by Beat poet and friend William S Burroughs. Befitting the iconoclastic outcast traits common to both Burroughs and Hart, the record is a roguish, humanised interpretation of Milton's epic poem set to post-punk pop melodies and a limited instrument set of predominantly drums, bass, guitar, organ and vocals. It's a tasteful, disciplined and ultimately very successful reworking – essentially, everything you would not expect it to be if you weren't aware of Hart's talents.

Equally unexpected is the friendship behind the record. Initially introduced to Burroughs in 1985 for a label photo shoot at the Beat poet's one-time New York haunt, The Bunker, Hart struck up an unlikely relationship with the ageing writer.

Equally unexpected is the friendship behind the record. Initially introduced to Burroughs in 1985 for a label photo shoot at the Beat poet's one-time New York haunt, The Bunker, Hart struck up an unlikely relationship with the ageing writer.

"We had lunch together and William was kind of showing us the way around handling a blow gun at this little target range," says Hart of their meeting. "I never read a lick of his work until the friendship had started. That put me in a very unique situation where he was more embracing because of the more natural acquaintanceship. In his words, he said that I didn't come to him with an agenda."

The friendship endured to the extent that, even after Burroughs died, Hart would still visit with the poet's assistant James Grauerholz, which, he tells us, is how he came to discover the inspirational treatment.

"I came over for a visit, James was working outside, it was a lovely summer day, and he handed me a five page manuscript," explains Hart. "It was William's Lost Paradise. [Director] Bob Wilson had put on [Burroughs' novel/play] The Black Rider and James was looking for something else that Bob could do something with… I decided, wherever it goes with James and Bob Wilson, this is an interesting project."

Processing a 500 page story of the fall of man through the filter of two of the world's finest literary minds and then into 20 pop songs is not an easy task. But like Milton's ambiguous poem, The Argument draws no absolute lines between good and evil; divine and damned. It fits then that Hart says his own spiritual upbringing was "free thinking… not necessarily religious, but we went to church." He also recalls a book of morality tales called Little Visits With God being left around the house.

It's a sort of cracked Hollywood musical, but with dark consequences behind the scenes

"I remember one time my Dad was cooling me down in the middle of the night and him saying, 'How do you think it makes Jesus feel when you keep your mother up all night?'" says Hart, prompted by the subject. "Years later, I ended up hating him for that sort of shit."

Grant never saw eye-to-eye with his father, who died earlier this year. The elder Hart became involved with another woman in later life and the songwriter believes the situation led to the decline in his mother's health and her eventual passing in 2011. But for all the bile directed towards his father, it's clearly his mother's experiences, not his own, that most concern Hart. A huge supporter of his creative output, it was his mother that helped secure the finance for Hüsker Dü's initial recordings and who encouraged a 10-year-old Grant to take up music in the first place.

"I inherited my first set of drums from a brother [who was killed by a drunk driver]," explains Hart. "Without me realising it at the time, as long as playing of the drums was involved, there wasn't much wrong I could do in the eyes of my parents."

His mother's influence on his creativity seems to be an enduring one. Even after her death, Hart concedes that she stills seems to have had an impact on The Argument. "If there was an effect on the record of her passing, it was that the song Glorious was probably less ridiculing of the concept of Christ, which ultimately serves the record well," says Hart. "[The lines] 'Glorious, yes I am/Glorious, you know I am' were already pretty piss-taking as it is, but… Essentially, I wouldn't have wanted to offend my mother. It was the first time when I wouldn't have gotten any reaction one way or the other." (Below: Hart, centre, in Hüsker Dü, with Bob Mould on the right)

That said, for all it's catchy melodies and abridgement, the record doesn't pull its punches. The schmaltzy, filmic qualities of tracks like "So Far From Heaven" and "Underneath the Apple Tree" conjure up images of a sort of cracked Hollywood musical – jazz hands and whistling onstage, but with dark consequences behind the scenes. Elsewhere, a song like "Golden Chain" highlights the much-debated scientific ideas contained within Paradise Lost.

That said, for all it's catchy melodies and abridgement, the record doesn't pull its punches. The schmaltzy, filmic qualities of tracks like "So Far From Heaven" and "Underneath the Apple Tree" conjure up images of a sort of cracked Hollywood musical – jazz hands and whistling onstage, but with dark consequences behind the scenes. Elsewhere, a song like "Golden Chain" highlights the much-debated scientific ideas contained within Paradise Lost.

"I think Milton's taking on the war that the church waged against science," explains Hart. "He was well acquainted with Galileo and the whole concept then was: 'Here's heaven. Here's earth. Here's chaos', but Milton chose to depict the earth as suspended from the sun by a golden chain, as if there was some sort of rotation intended… Then there's a point where the angel Raphael says to Adam, 'Is there anything else you want to know?' And Adam is like, 'Yes, I'm very interested in the movement of the heavens.' [And the response is] 'That is not for you!'"

These are big ideas, but to Hart's credit The Argument captures them in a form that is somehow relatable. Like his best work in Hüsker Dü, a song like "Is the Sky the Limit" offers genuine emotional gravitas in a devastatingly efficient form.

Listen to "Is the Sky the Limit"

"The goal was to allow every song to stand on its own outside of the whole drama," Hart explains. "With the exception of [second track] Awake Arise, that has pretty much prevailed. Awake Arise – well, if somebody's ascending from a lake of fire and building a new pandemonium, you pretty much have to hit that nail on the head..."

While the vast majority of the album works in a universal sense, the most tender, personal songs tend to be those told from the point of view of the outcast Satan. It's definitely too cute a theory, but we can't resist asking if, in light of his experiences as the unappreciated scapegoat post-Hüsker Dü, Hart doesn't feel a certain sympathy for, err, the devil?

"I would not work too hard to convince anybody otherwise," he concedes. "In any kind of dramatic presentation, you're going to find the author identifying with the protagonist, whether it's a hero or an anti-hero. But, as we un-peel the onion, I would say that is a valid hypothesis."

In The Argument we've got beat writers, epic poetry and both personal and literary demons addressed. There's even talk of bringing ballet dancers in for a conceptual live show. At this point in their lives, many rock musicians are penning contemplative, unrewarding acoustic records – not producing challenging double albums that stand up against their best material. By that token, the record is something of a rebellion itself.

"I feel that it's never too late to do great stuff," he says, as our discussion draws to a close. "There's a piece of me that has always resented people not being able to get past my 23rd year. I need to satisfy the part of me that wants to be an artist in it for the long run."

Point proven, we'd say.

Add comment