Art of America, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

Art of America, BBC Four

Art of America, BBC Four

A deeply impressive retelling of the story of American art from its colonial beginnings

For dull reasons to do with a dodgy digital box and a very old analogue telly, I can’t tune in to BBC Four during live transmissions, so I either catch up on iPlayer, or (lucky me as a journalist) get to see programmes early. But I’m very glad I can get it at all, for when the BBC cuts come to pass and its premier arts channel starts broadcasting archive-only material, as it proposes to do, then I think I might just stop watching telly altogether.

This is because everything, but everything, that the BBC stands for is encapsulated by BBC Four’s original programming. And in the visual arts it excels – it’s the channel where I can sit back and not be patronised by Rolf Harris “doing Impressionism”. Bliss. You seriously don’t get this type of coverage on any other channel.

For one thing, Andrew Graham-Dixon is the doyen of TV visual arts. His programmes are erudite, but they wear their erudition lightly. And he takes in the broad cultural sweep, the pulse and the temperature of a nation through its art. His previous series took us on grand, magisterial tours of the histories of Russian art, then Italian Renaissance art (harder, since we think it’s all so familiar), and then German art, which I found to be the most riveting (not just because of its art, but what the presenter had to say about how the contradictory impulses at the heart of German society were so eloquently expressed through its art).

He’s taking the westward journey from the eastern seaboard, just as the original pioneers had

And now we have Art of America, which, true to its subject and the subject’s vast geography, is a cross between a latter-day televisual Tocqueville (kind of – seen, if you can take the imaginative leap, not through the lens of political science but through art) and an American road movie – there are as many shots of Graham-Dixon speeding along highways as there are of him gesticulating in front of paintings. He’s taking the westward journey from the eastern seaboard, just as the original pioneers had, and, in turn, looking at the images that helped build a uniquely American identity.

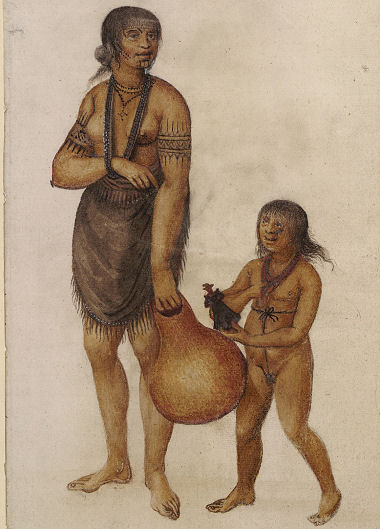

We begin at the beginning – the beginning, at least, of the first failed attempt to build a white American settlement. And we begin with the aptly named John White. White was an artist who arrived at Chesapeake Bay in 1585 to record its rich flora and fauna, and just like so many of those who came after, White thought he’d found a New Eden. Through his paintings he hoped he’d encourage new settlers to this uncharted idyll.

But it all went disastrously wrong. The virgin colonialists were ill-prepared – they had neither livestock nor, it appears, any understanding of how to harvest the land. What’s more, there were growing hostilities between the settlers and the native Americans. So in desperation White returned to England for supplies.

By the time he came back, some two years later, the entire colony had disappeared, including his daughter and granddaughter, the first American-born child of European parents. To this day we don’t know what happened, but we still have White’s quietly eloquent and sensitive pictures of the native Algonquin (pictured right: A cheife Herowan's Wyfe; British Museum). The art and the artefacts of the native American, meanwhile, remain painfully silent to us: "When you destroy entire sets of civilisations, you also destroy the possibility of writing its history."

By the time he came back, some two years later, the entire colony had disappeared, including his daughter and granddaughter, the first American-born child of European parents. To this day we don’t know what happened, but we still have White’s quietly eloquent and sensitive pictures of the native Algonquin (pictured right: A cheife Herowan's Wyfe; British Museum). The art and the artefacts of the native American, meanwhile, remain painfully silent to us: "When you destroy entire sets of civilisations, you also destroy the possibility of writing its history."

Inevitably, a dark thread runs through Art of America’s first episode (of three), for the birth of a nation told through its images is rarely a reliable tale and brutalities are neatly skirted. From Benjamin West's depictions of American Independence to Thomas Cole's Course of Empire series, the paintings do, however, reflect the hopes, the ambitions, as well as the unease of a nation.

But though its people were pioneering, its art, on the whole, wasn’t – what Graham-Dixon sums up as “Protestant and provincial”. Early portraits are second-rate European, he tells us - not quite Van Dyck, not quite Gainsborough. And this is quite true – certainly there is a lack of European sophistication: American art of this period characteristically possesses a sturdy homeliness; at best a charming naivety. And this says as much about the division between the old world and the new as anything in a Henry James novel.

What comes later for American art is where it gets really interesting. After this impressive first episode, I trust you'll keep watching.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

You're spot on about the

What a compelling

Evidently we need to persuade

is it possible to buy all the

This video "Art in America "