Leonard Cohen: Bird on a Wire, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

Leonard Cohen: Bird on a Wire, BBC Four

Leonard Cohen: Bird on a Wire, BBC Four

Impressionistic, poetic, enigmatic portrait of the songwriter on tour in 1972

The renaissance enjoyed by Leonard Cohen over the past few years is not only thoroughly welcome and entirely justified, but also partly a testament to the strange and powerful alchemy that sometimes occurs when the defiantly high-brow is swallowed whole by popular culture.

More prosaically, the decision – forced upon him by the alleged misappropriation of over $5m from his pension fund by a former manager – to begin touring again in 2008 after an absence of 15 years has written a hugely successful and ongoing third act for his career, rebranding Cohen at 76 as a benevolent, trilby-doffing roué, an old-school charmer in the garb of a Mafia capo.

We also saw the nightly complications of the lethal lothario, only a little put off by the presence of a camera and the language barrier

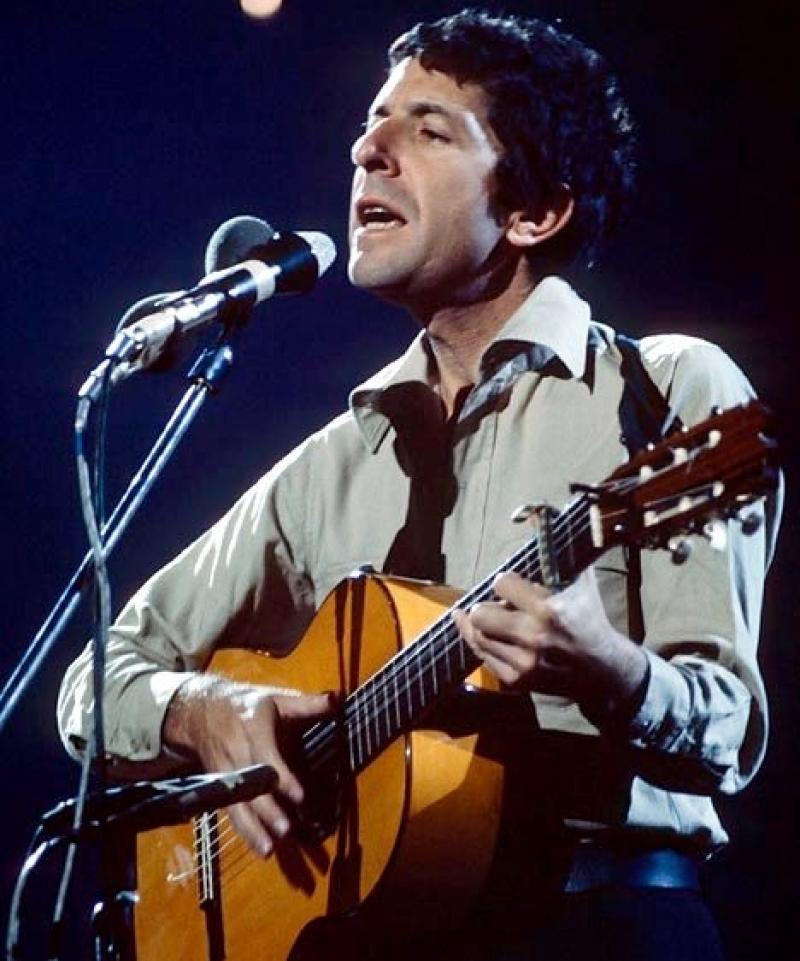

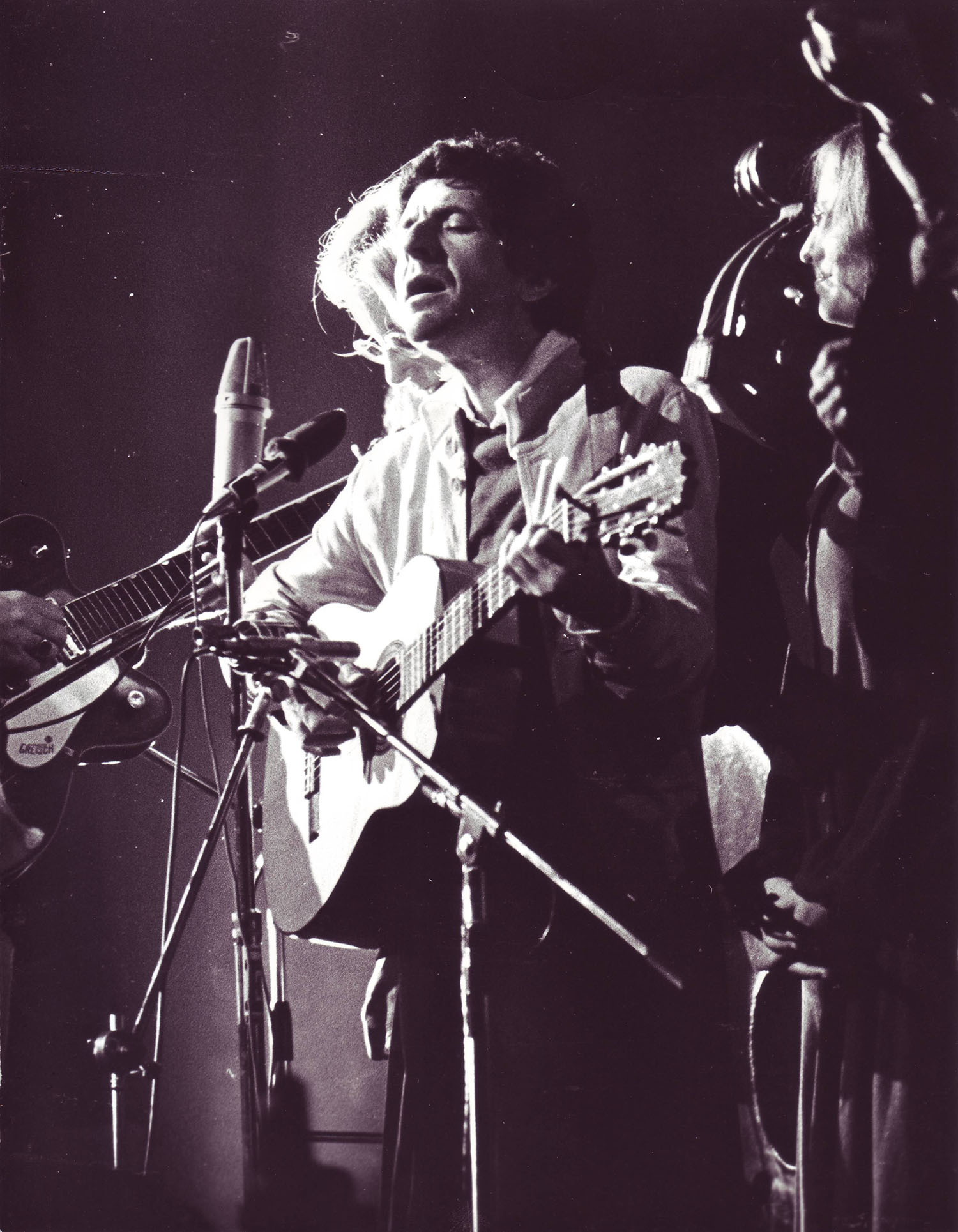

Shown on BBC Four last night in a restored version of the original cut, Tony Palmer’s superb documentary Bird on a Wire took us back half a lifetime and portrayed an altogether more conflicted soul. It was filmed during Cohen’s 20-city tour of Europe in the spring of 1972 and described itself at the start as an “impression” of that tour. And that's precisely what it was – impressionistic, poetic, enigmatic, perfectly in tune with its subject. There was no attempt to contextualise Cohen in terms of his past achievements or his life outside of the bubble of the tour. This was a film about an artist striving to maintain a point of stillness – “I prefer not to speak at all” – in a sea of almost constant clamour and commotion.

It was one of the best attempts I've seen to examine the extraordinary conditions under which a performing artist has to work, trying to inhabit moments of heightened awareness and retain an accessible sense of self amid ceaseless interruptions and demands for explanations. Aged 37 in 1972, as well as a generation's favourite tortured artist, Cohen was already a successfully published poet and novelist who had learned that “success is survival”.

It was one of the best attempts I've seen to examine the extraordinary conditions under which a performing artist has to work, trying to inhabit moments of heightened awareness and retain an accessible sense of self amid ceaseless interruptions and demands for explanations. Aged 37 in 1972, as well as a generation's favourite tortured artist, Cohen was already a successfully published poet and novelist who had learned that “success is survival”.

On stage, he and his band were plagued by rogue monitors and ghost-riddled sound systems. He simmered with all the frustration of a poet whose words couldn't be heard. At one point he stood in the foyer of an Oslo theatre and gave two stern fans – peeved beyond parody with righteous fury – their money back from his own pocket, art forced to bow to commerce.

Backstage it was a whole other world. Palmer’s film recalled Don’t Look Back, D.A. Pennebaker’s celebrated documentary of Bob Dylan’s 1965 British tour, in its fascination with the ecology of the after-show environment. His camera penetrated the outer crust of hangers-on, journalists and facilitators that seemed to squeeze all the air from Cohen’s lungs as he crouched in his dressing room, a shower of devotees surging at the door. The quiet, bearded fans clutching books of verse were more viciously demanding than any teeny-bopper screaming at a piece of pop fluff.

These intrusions were spontaneous and genuinely invasive. Palmer's camera, of course, was invited. This was a knowing self-portrait which left Cohen’s enigma preserved and indeed enhanced. It captured a man profoundly aware of his own charm and mystique.

When we saw him reading poetry as curlicue of smoke drifted through his hotel suite, a bottle of champagne lounging in the foreground, the scene couldn't have been better choreographed had it been a Vanity Fair photo shoot.

We also saw the nightly complications of the lethal lothario. At one point Cohen, only a little put off by the presence of a camera and the language barrier, worked his legendary charm on an almost indecently willing victim. Later, in one of the film’s most uncomfortable scenes, a recent conquest approached him backstage and asked, “Do you remember me?” He squirmed his way out of making an appointment, muttering “I feel like I’m going to disgrace myself”.

We also saw the nightly complications of the lethal lothario. At one point Cohen, only a little put off by the presence of a camera and the language barrier, worked his legendary charm on an almost indecently willing victim. Later, in one of the film’s most uncomfortable scenes, a recent conquest approached him backstage and asked, “Do you remember me?” He squirmed his way out of making an appointment, muttering “I feel like I’m going to disgrace myself”.

The music wasn’t quite centre stage but instead wove around the images and the drama. There were fabulous renditions of what he dismissively described as “museum songs” like “Suzanne” and “Sisters of Mercy”, as well as a magnetic, thoroughly self-disgusted version of “Chelsea Hotel”. Throughout, for minutes at a time, Palmer’s camera sat tight on Cohen's face, finding in it all the action required.

His voice too, whether singing or reciting poetry, was mesmerising. He characterised his music as a mixture of chanson and synagogue cantor, and himself as “a broken-down nightingale” trying to “move a song from lip to lip”. There was a lot of this kind of superior stoned rambling; at times he looked utterly out of it. “Each man has a song, and this is my song,” he proclaimed wearily. For anyone crying solipsism, he argued that “loneliness is a political act”. It sounded like prime rock-star bullshit until Palmer mixed footage of him singing “Story of Isaac” with still-shocking images of extreme military and political violence, at which point suddenly it made a very powerful kind of sense. On stage in Manchester he imagined the theatre as a ruin: “It’s well on its way,” he drawled. “And I hope the banks follow...”

At the end of this extraordinary film you could see why he eventually disappeared for five years to live in a Buddhist Zen monastery

Geographically, the film ended where it began, in Israel. The opening scenes of Bird on a Wire were shot in Tel Aviv and showed hired goons in orange overalls beating up fans who wanted to move to the front of the hall. One hundred minutes later it climaxed with Cohen “bombed in Jerusalem” on the final date of the tour. As a Jew – “Practising? Oh, I’m always practising” - the context clearly had major cultural and personal resonance for him, and the tension that had been building throughout the film suddenly snapped.

Earlier he had described the process of singing live thus: “Sometimes you are living in a song, and sometimes it’s inhospitable and won’t admit you, and you’re left banging at the door and everybody knows it.” In Jerusalem, palpably nervous (not to mention out of his tree), Cohen was shown banging on that door to no reply, delivering a bitty, nervy, disjointed, apologetic performance which ended abruptly and prematurely with him quoting the Kabbalah and announcing that, tonight at least, “God does not sit on His throne”. Eventually, propelled by the devotion of the crowd, he came back out.

Backstage he sobbed: worn out, worn down, a fascinating jigsaw of rampant ego (“I can always be talked into going out to sing another song!”), exhaustion, high emotion, relief, chemically-induced fragmentation and intense self-loathing. At the end of this extraordinary film you could see why he eventually disappeared for five years to live in a Buddhist Zen monastery. You could also see – just; like a deer glimpsed darting through the woods - why he came back.

Watch a clip from Bird on a Wire:

- Watch Bird on a Wire on BBC iPlayer

- Find Bird on a Wire on Amazon

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment