Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam, British Museum | reviews, news & interviews

Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam, British Museum

Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam, British Museum

Both scholarly and profoundly moving, an in-depth exploration of one of the five pillars of Islam

Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam is an exhibition about faith that even an avowed atheist might find rather moving. The last of the British Museum’s series of in-depth exhibitions exploring aspects of the three great Abrahamic religions, the exhibition attempts to shed light on what is, to outsiders at least, the most mysterious of religious rituals.

For those who know little of Islam, Hajj is the pilgrimage to Mecca that must be completed by every Muslim if they are fit and able, at least once in his or her life, as the Prophet Mohammed himself did in the last year of his. It is one of the pillars of Islam and takes place during the last month of the Islamic year, known as Dhu’l Hijja. This year around three million pilgrims are expected to congregate for a spiritual journey that is both personal and communal.

We are offered fascinating glimpses of a world that has always been closed to non-Muslims

Since pilgrims now come from all corners of the globe, the first part of the exhibition concentrates on the history of this once perilous journey in which, long before the days of air travel and convenient packages tours, sickness and death – whether by cholera and other communicable diseases or by the hand of the occasional murderous bandit – were not uncommon. Whether that journey was taken by boat or by camel, over several weeks or many months, we see the four main routes to Mecca broadly mapped out for us, including one of the earliest: a road in what is now Iraq established at the turn of the 9th century by Zubayd, wife of Harun al-Rashid of Arabian Nights fame. It comes complete with staging posts and reservoirs for necessary rest and refreshment.

Under the great dome of the British Museum’s Reading Room, visitors move in a circle as they pass by each display area, replicating the anti-clockwise motion of pilgrims as they encircle the Ka’ba, the cube-shaped granite building that Muslims believe was built by Abraham and his son Ishmael. The Ka’ba is, in fact, encircled seven times, a ritual that enacts Abraham’s inspection of the Ka'ba when it was completed, after Adam’s original construction. Further rituals, all of which last a total of six days, sees the drinking of holy Zamzam water (right: a 19th-century bottle containing Zamzam water) from a local fountain, enacting the discovery of water by the parched and frantic Hager after Abraham abandoned her and their baby son in the desert, and the throwing of stones at a pillar to enact the casting out of the devil by this same prophet.

Under the great dome of the British Museum’s Reading Room, visitors move in a circle as they pass by each display area, replicating the anti-clockwise motion of pilgrims as they encircle the Ka’ba, the cube-shaped granite building that Muslims believe was built by Abraham and his son Ishmael. The Ka’ba is, in fact, encircled seven times, a ritual that enacts Abraham’s inspection of the Ka'ba when it was completed, after Adam’s original construction. Further rituals, all of which last a total of six days, sees the drinking of holy Zamzam water (right: a 19th-century bottle containing Zamzam water) from a local fountain, enacting the discovery of water by the parched and frantic Hager after Abraham abandoned her and their baby son in the desert, and the throwing of stones at a pillar to enact the casting out of the devil by this same prophet.

There is much text, though few material riches to marvel at – ancient, pictorial maps of Mecca and Qiblas (compasses that point the worshipper towards Mecca during prayer; left: Ivory sundial and Qibla pointer, Turkey, 1582-3), plus a section that includes the modern-day souvenir tat you can buy once there – so there’s a short film at the beginning of the exhibition that helpfully makes sense of it all.

There is much text, though few material riches to marvel at – ancient, pictorial maps of Mecca and Qiblas (compasses that point the worshipper towards Mecca during prayer; left: Ivory sundial and Qibla pointer, Turkey, 1582-3), plus a section that includes the modern-day souvenir tat you can buy once there – so there’s a short film at the beginning of the exhibition that helpfully makes sense of it all.

En route, in the form of excerpts from the journals of individual pilgrims, we are offered fascinating glimpses of a world that has always remained closed to non-Muslims. These include those of the intrepid Victorian explorer and orientalist Richard Francis Burton, who did the Hajj in 1853 disguised as an Afghan doctor.

This first translator into English of the Kama Sutra published his detailed account of his Hajj adventures in two volumes. But he wasn’t the earliest recorded non-Muslim explorer to venture into Mecca’s sacred centre. This is an honour that belongs to an intrepid 16th-century Italian. Meanwhile, we find accounts given by contemporary British Muslims - a 10-year-old North London schoolgirl offers hers in a most eloquently voiced hand-written diary.

We are reminded of the exclusion of non-Muslims by an artist’s copy of a motorway sign separating the route for Muslims and non-Muslims, whilst Idris Khan's inscrutably layered text piece I was Here for You and Only You, hits a more inclusive note, addressing devotional questions - “Are you leaving as you had come?” – to the gallery-goer turned mini-pilgrim. For the Welsh-born Khan the question is a deeply felt one: he expresses the profound, transformative impact the Hajj had on his Pakistani father.

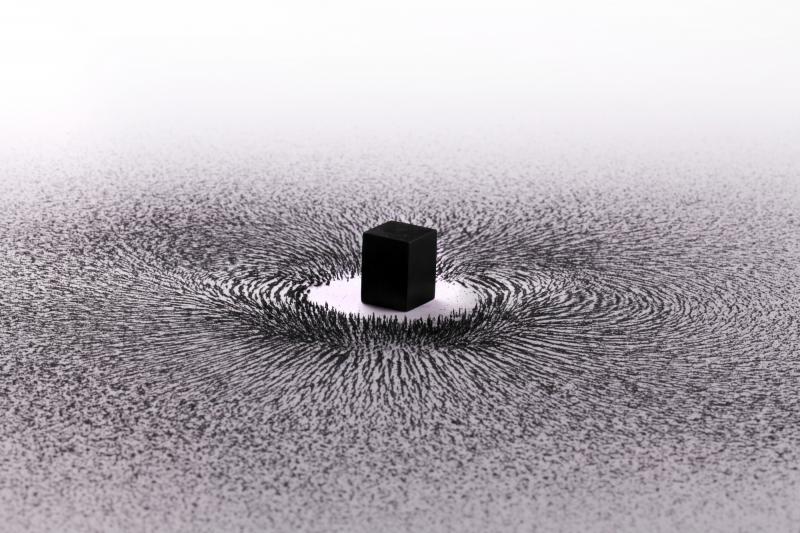

But perhaps the artwork that best sums up the experience visually is Ahmed Mater’s Magnetism (main picture), a black magnetic cube placed in the centre of a sheet of white paper encircled by tiny magnetic filaments, some prone, some quiveringly erect. Resembling one of the time-lapse films that greet you at the start of the exhibition, it’s a work that, in its simplicity and directness, gently reminds you that faith is an act of submission to a will far greater than any other. And this is exactly what Islam, in its translation, means.

Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam at the British Museum until 15 April

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious