Interview: Director Pawel Pawlikowski | reviews, news & interviews

Interview: Director Pawel Pawlikowski

Interview: Director Pawel Pawlikowski

BAFTA-winning Polish-born director of The Woman in the Fifth on England, madness and movies

Pawel Pawlikowski was named BAFTA’s Most Promising Newcomer for his feature debut Last Resort (2000), then the follow-up, 2004’s My Summer of Love, won Outstanding British Film of the Year. But neither felt obviously British, reflecting border-zone existences in a sometimes beautiful, sometimes horrific country.

The director’s latest, The Woman in the Fifth, makes Paris equally strange, leaving Ethan Hawke’s troubled American writer Tom abandoned in its furthest, forgotten suburbs, where he does mysterious jobs for the criminal who runs the café where he’s holed up, and pines for the child kept from him since some awful excess.

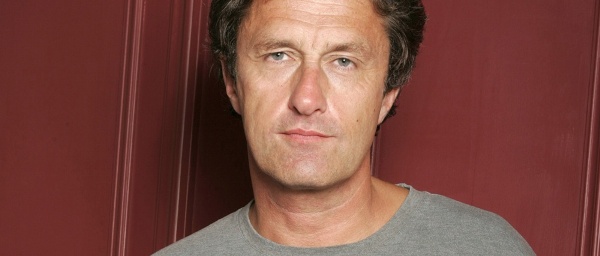

Born in Warsaw, Pawlikowski (pictured right) first visited Britain in 1971, aged 14, living in several European cities before settling in the UK with his Russian wife and two children. His wife’s sudden illness and death in 2007 put his professional life on hold while he focused on raising his children, and they now live in Paris. He speaks six languages, and is fluent in philosophical flights of longing too when we meet in London. He seems to have been an exile since he first saw England as an adolescent: always observing from the outside.

Born in Warsaw, Pawlikowski (pictured right) first visited Britain in 1971, aged 14, living in several European cities before settling in the UK with his Russian wife and two children. His wife’s sudden illness and death in 2007 put his professional life on hold while he focused on raising his children, and they now live in Paris. He speaks six languages, and is fluent in philosophical flights of longing too when we meet in London. He seems to have been an exile since he first saw England as an adolescent: always observing from the outside.

“Yeah, well,” he considers. “That’s more an existential choice than anything, because I could have become more British - I feel vaguely British. I’ve lived in Germany, Italy, my wife was Russian. If you’re an exile, you tend to marry into the tribe [where you live], so at least there are some rules. So I seem to like being on the margin, in every way, even filming. Of course in cinema, which makes a lot of noise and is expensive, it’s tricky to be on the margins.”

The Woman in the Fifth goes the furthest out of his three features so far, into poetically unsettling visual language. It takes the tight narrative of the Douglas Kennedy thriller it’s based on and uncrosses ‘t’s and undots ‘i’s, till we’re in paranoid terrain neighbouring that of his countryman Polanski.

“Every viewer picks up on different things, there’s no clear turning point,” Pawlikowski says of this vertiginous descent into nightmare. “People spot the rot setting in their own time - even when the plane lands crookedly right at the start. Even when I did My Summer of Love, which is a relatively straightforward drama, people sided with or loved different characters. Film is this bizarre thing. It’s just there, and you project what you know onto what’s going on on-screen, and everyone projects different things. Every film’s a crooked mirror, in a way. And this film is more crooked than any other! That’s the idea, anyway. Which is a risk, in terms of mass audiences.”

Watch the trailer to My Summer of Love

I felt the bottom fall out of Tom’s world when he meekly hands his passport to an unscrupulous landlord. It leaves him in the same purgatory as Tanya, the émigré stopped at Customs and trapped in Last Resort’s Margate limbo. Crossing borders with his parents as a child, Pawlikowski glimpsed that purgatory. “Some kind of Eastern European complex!” he laughs. “I remember losing a passport once in Moscow. Once you lose it in certain parts of the world, your life will never be the same. When I first had a Western passport, it was such a weird feeling crossing borders. All of a sudden you don’t have to justify yourself, they have to treat you like a human being, you won’t be humiliated. Whereas if you lose this foreign passport, then you are at the mercy of whatever happens. The Russians have a phrase that means ‘anything goes’. No limits.”

The script Pawlikowski abandoned for The Woman in the Fifth described a blunter descent into madness. Remembering his wife’s death, I wonder if this responded to a deep crisis of his own. “Yes, slightly. But it’s kind of personal. It’s about a mother who’s in a mental asylum, and a 14-year-old son who springs her from it. But when you look at insanity from outside, it’s kind of boring, because the behaviour is circular and frustrating and exhausting and doesn’t lead anywhere. It was much more interesting to somehow try and get into the deranged state of mind, which is impossible unless you’ve been there. And that’s what I’m doing with this film.” Insanity can also be surprising, as brains suddenly spark with paranoid intellectual intensity, in previously unlikely people. “Yes, fixating on people who can save you,” he agrees, “and who are devils and can destroy you. That’s like a thriller too. They’re both slightly unreal, but functions of similar needs.”

Pawlikowski entered the country where he was first a stranger in a strange land at the fag-end of hippie London. At first, he was intrigued. “I didn’t speak any English,” he recalls. “But I was seeing all of these attractive elements, people with long hair, and a certain freedom of behaviour. And then I came to the English provinces, to Henley-on-Thames, and it was totally weird, with people not saying what they mean, not looking at you, as if you’d done something wrong. The rules of the game were so different than back home. This lack of a kind of warmth, I suppose.”

Pawlikowski entered the country where he was first a stranger in a strange land at the fag-end of hippie London. At first, he was intrigued. “I didn’t speak any English,” he recalls. “But I was seeing all of these attractive elements, people with long hair, and a certain freedom of behaviour. And then I came to the English provinces, to Henley-on-Thames, and it was totally weird, with people not saying what they mean, not looking at you, as if you’d done something wrong. The rules of the game were so different than back home. This lack of a kind of warmth, I suppose.”

Pawlikowski has spoken previously of disappointment with the growing pragmatism of the British since he’s known us - a faltering of imagination, or any wish for transcendence. Now he lives in Paris, he’s less sure. “Transcendence is not the thing,” he ponders. “Erotic desire’s not the thing either. But there is something that’s elusive and fascinating about the English mind - this unspoken quality, these unwritten rules. In fact, the film that I abandoned [half-finished] because of my wife’s untimely death was The Restraint of Beasts, based on a fantastic book by Magnus Mills. It’s about Scottish fence-makers and their English foreman, and they live in this world of minimal statements - [mumbling] ‘Aw’ight.’ ‘Ye’’. Nobody actually speaks with any commitment to communicate! It’s ritualised, and it could mean all sorts of things, a bit like Pinter’s plays, if you start filling in the gaps. Are they trying to kill me? What’s going on here? There’s that unspoken frustration, and aggression. That creates amazing monsters, and fascinating possibilities, dramatically. That carried on to this script.”

It sounds like this submerged, oblique quality makes the place perfect for Pawlikowski. “Yeah, maybe. I’ve always loved Pinter, since I was a kid. And then of course [Polanski’s 1966] Cul-de-Sac, which is Polish absurdism, but very English too. I’ve been living a normal life with two kids and dealing with things in England, and it’s kind of drab, you know. But now I’ve moved, it’s working on my imagination. You’ve got the landscape you live in, and the landscape of places you’ve been that stays with you.

“England is definitely really powerful,” he continues, “especially strange edges like the Thames Estuary, or West Yorkshire (the setting for My Summer of Love, pictured above). Even coming here this week on the Eurostar, just after Ashford in Kent, there’s this landscape which is like a No Man’s Land. The sun was very strong and quite low, so you saw a bit of water here, a shack, power plant, road - it was a complete degraded landscape, but immediately had a metaphorical resonance. It’s about surprising arrangements of objects, not too many, in the shot. I enjoy being in places which haven’t been worked over too much, by the logical machinery of today’s industrialised, mechanised, electronic universe - this Moloch that we are committed to now. I like things which don’t make obvious sense, or which are not functional. I like films like that too. I like ones which leave space for you to fill in, like life, which is never coherent.”

Before Pawlikowski became a feature director, he explored odd corners of Europe as an award-winning documentarian, interested, he said, in “surreal tales of small people caught up in the vortex of history”. In Serbian Epics (1992), for instance, he persuaded the war criminal Radovan Karadžić to stand on the hills above Sarajevo, reading poetry prophesying its destruction; in the same year’s Dostoevsky’s Travels, he observed the novelist’s great-grandson’s eccentric travails. But he doesn’t expect to return to non-fiction. The world he was documenting has, for him, disappeared.

Panic in the streets: Ethan Hawke in Pawlikowski's Paris

Panic in the streets: Ethan Hawke in Pawlikowski's Paris

“Places are much more aware of themselves,” he explains. “There was something half-baked at the time, Communism was collapsing and the 19th century was still palpable, strangely, capitalism was creeping in. It felt fresh, with a space to imagine things, and authentic. If you go to Poland, Russia, anywhere now, they’ve got exactly the same TV stuff, young girls and boys look more or less the same as anywhere else, and everyone’s filming themselves like idiots. So suddenly being on the edge of something unknown - that’s gone.”

The so-called Iron Curtain Pawlikowski was born behind may then have done Eastern Europe an accidental favour, preserving it; at a different cost, as he of course knows. “There was a different sort of inauthenticity,” he thinks back. “The Communist newspeak, and the image-making there was just so grotesque and off it’s head, that in a way I’d rather suffer the mediocre reality of this than that. But because the official version of events was so deeply inauthentic, and most people knew it, it left a lot of space for authenticity, strangely. Now inauthenticity is creeping into every pore, like this food,” he says, looking at the stacked sandwiches in the blank London conference room where we’re sitting, “which is very colourful and none of it has any taste. It just fulfils a dramatic role while we talk. Even art-house films look like art-house films, but they’re completely by numbers. There are rules which are as mechanised as the films made by Hollywood. I prefer Hollywood, actually. It’s very difficult to escape into something that’s not quite measurable, predictable, manipulatible. Part of this weird monster of a film I’ve made is to escape all sorts of schemes. But the danger is it falls between every possible stool, commercially…”

Does Pawlikowski want his films to take people out of the solid, over-mediated world that offends him, to somewhere they can think freer thoughts?

“It’s not like my Five-Year-Plan to do it,” he says. “But I hope people recognise themselves in it somehow. That’s the whole idea. I want people to be moved. People say this film’s so mysterious and clever - maybe it’s too elliptic. But some versions of it, I was really crying. The story of the hero is a tragedy, you know. I cut one scene which made that even more clear. Suzy one of the producers used to cry every time, then at some point she didn’t. I said, ‘Why? Have I taken out too much?’”

There’s a suggestion in The Woman in the Fifth that Tom subconsciously goes through the film’s torments to help with his stalled writing. “Play your cards right,” Kristin Scott Thomas’s muse seductively whispers, “and this could be a real tragedy.” Is Pawlikowski that ruthless an artist?

“On the contrary. I’m a family man. I used to be much more, before my kids. But now task number one is to survive. I’m not like some of the Russian documentary directors I see, like Kossakovsky, so single-minded, with such will at work. I leave real art to those extremists.”

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

Add comment