Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World, British Museum | reviews, news & interviews

Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World, British Museum

Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World, British Museum

The history of this troubled nation comes alive through its treasures

I’m in an exhibition of ancient artefacts from Afghanistan, all from the National Museum at Kabul, but I may well have stumbled into the wrong room at the British Museum. I could be in the BM’s Hellenic section of Greek art, or, taking a few steps to my left, the Egyptian rooms.

Afghanistan, a country whose recent war-torn history is part of our own, has always been at the intersection between East and West. It might have taken two years for an army to get from mainland Greece to north Afghanistan, but Alexander the Great was a man undeterred by huge distances over tough terrain. On his way to conquering parts of Iran and India, his armies settled in Bactria, in a region that later became known by the name of Ai Khamoun (meaning Lady Moon, after a local Uzbek princess). Excavations here almost 50 years ago unearthed a Greek civilisation, complete with gymnasium for intellectual as well as physical training.

But then, in 1979, came the Soviet invasion, and then, eventually, the Taliban. What the invading armies of the 20th century hadn’t damaged or destroyed, the Taliban purposefully did their best to finish off two decades later. They destroyed the ancient Buddhas of Bamiyam in the centre of the country, and they broke into the Kabul museum to erase their country’s past.

Luckily, unlike the lost Buddhas, the treasures you’ll find in this exhibition were rescued. Most were hidden in secret locations by museum workers. Thanks to them, the world now has a chance to see the rich and diverse past of a country that once lay at the heart of the Silk Road, and at the outermost regions of Alexander’s empire (pictured right: Corinthian capital, Ai Khamoun, before 145BC).

Luckily, unlike the lost Buddhas, the treasures you’ll find in this exhibition were rescued. Most were hidden in secret locations by museum workers. Thanks to them, the world now has a chance to see the rich and diverse past of a country that once lay at the heart of the Silk Road, and at the outermost regions of Alexander’s empire (pictured right: Corinthian capital, Ai Khamoun, before 145BC).

This exhibition comes in four sections, but as an opener, we’re first confronted by a headless youth carved in limestone. It is a Hellenic bas-relief of a naked boy who is over 2000 years old.

Unfortunately, he is not just headless but he no longer has a penis, and there’s some considerable damage to his legs. The damage to the lower body is, in fact, not recent. At some point in the distant past, vandals attacked the sculpture. When it was discovered by French archaeologists in the Seventies, it was taken to the National Museum, and this is where it was attacked again, this time by the Taliban. It’s been painstakingly pieced together, but the head has never been recovered.

In the first section you’ll find artefacts that are even older: fragments of gold vessels, delicately incised with geometric patterns or sinuously etched animals and dated to around 2,000BC (pictured left: fragment of bowl depicting bearded bull). These Bronze Age vessels were unearthed from a site known as Tepe Fullol. Gold was originally discovered on the site by a group of Afghan farmers in 1966, and French archaeologists soon hurried to the site, unearthing the precious fragments. It was the first sign of a previously unknown and wealthy civilisation.

In the first section you’ll find artefacts that are even older: fragments of gold vessels, delicately incised with geometric patterns or sinuously etched animals and dated to around 2,000BC (pictured left: fragment of bowl depicting bearded bull). These Bronze Age vessels were unearthed from a site known as Tepe Fullol. Gold was originally discovered on the site by a group of Afghan farmers in 1966, and French archaeologists soon hurried to the site, unearthing the precious fragments. It was the first sign of a previously unknown and wealthy civilisation.

From there, we move swiftly through time - two millennia, in fact - to Alexandra the Great. The Greek settlement at Ai Khanoum was founded by Selelicus I, one of Alexander’s generals in around 300BC. As well as the gymnasium mentioned above, the city had a theatre, a temple and a sumptuous palace, all decorated in the distinctive Greco-Bactrian style.

But the fall of the city came suddenly, having survived little more than 150 years. Nomads from the north-east, displaced from Chinese central Asia, entered the region and destroyed Ai Khanoum. They set fire to the palace and robbed it of its treasures. Local people outside the city walls moved in, plundering further what the Greek colonists had left behind, while a second nomadic raid some 15 years later saw the city looted once more.

Descendants of these nomadic tribes eventually formed a civilisation now known as the Kushan, whose story forms part of the third and possibly most enthralling section of this exhibition.

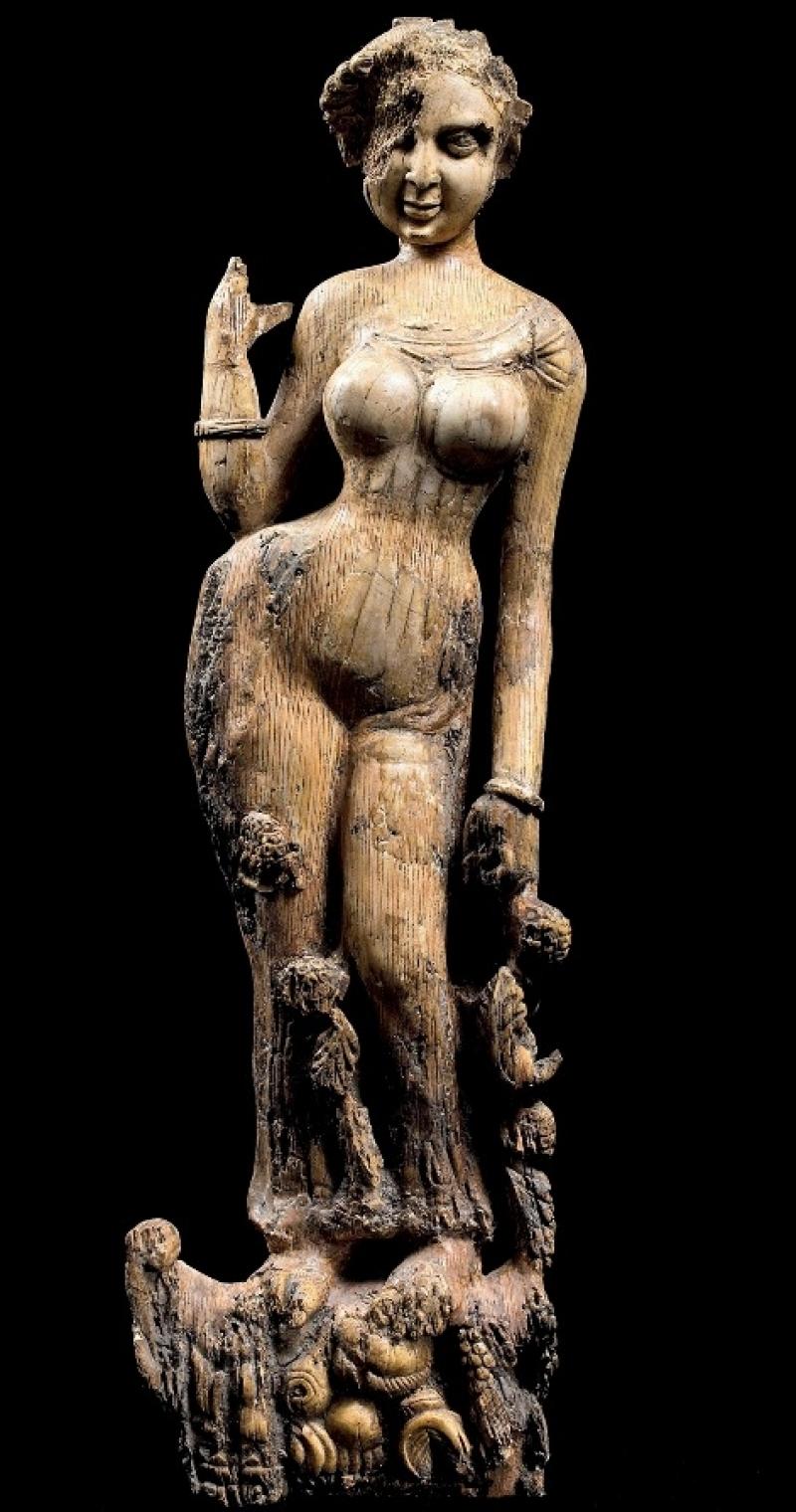

The treasures here were recovered from the site of Begram’s Summer Palace. The palace had been abandoned - in fact, walled up - in the first century AD by one of the ruling families of the Kushan, and the treasures hidden. However, for reasons that remain unknown they never returned to reclaim their hoard. These objects testify to the rich trade with India and Rome: beautiful and intricate Indian ivories; brightly painted and delicately moulded Roman glassware (pictured right); and statuettes that are a combination of Greek and Egyptian imagery, such as the tiny sculpture of Hercules wearing the crown of the Egyptian god Serapis.

The treasures here were recovered from the site of Begram’s Summer Palace. The palace had been abandoned - in fact, walled up - in the first century AD by one of the ruling families of the Kushan, and the treasures hidden. However, for reasons that remain unknown they never returned to reclaim their hoard. These objects testify to the rich trade with India and Rome: beautiful and intricate Indian ivories; brightly painted and delicately moulded Roman glassware (pictured right); and statuettes that are a combination of Greek and Egyptian imagery, such as the tiny sculpture of Hercules wearing the crown of the Egyptian god Serapis.

The last section contains even more gold than the first. We’re now amongst the glittering relics discovered buried within six hillside tombs in Tillya Tepe (in the north) in 1978 (the Uzbek name Tillya Tepe aptly translate as "Hill of Gold"). The burials – one man and five women – are dated to the first century AD. Buried with them were 20,000 objects of gold and semi-precious stone.

Here we find a collapsible crown of beaten gold, made for a nomadic princess (pictured left). Each section, fashioned in the shape of a tree, comes apart for ease of transportation. Smaller items include several decorated Chinese hand mirrors, a cosmetics box, countless items of jewellery and a pair of gold soles, for shoes which were not used for walking but which would have had a dramatic effect when the wearer sat down.

Here we find a collapsible crown of beaten gold, made for a nomadic princess (pictured left). Each section, fashioned in the shape of a tree, comes apart for ease of transportation. Smaller items include several decorated Chinese hand mirrors, a cosmetics box, countless items of jewellery and a pair of gold soles, for shoes which were not used for walking but which would have had a dramatic effect when the wearer sat down.

There’s an awful lot of cross-cultural history to absorb in this exhibition. Thankfully, it's small enough to relish each object in turn, whilst large enough to give a fascinating and extensive overview.

- Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World at the British Museum until 3 July

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment