theartsdesk in Moscow: Russia on British Screens | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Moscow: Russia on British Screens

theartsdesk in Moscow: Russia on British Screens

New Russian cinema: overcast with occasional sunny intervals

Russians are prone to ask the big questions, and among them, resonating periodically and patriotically, from film studio corridors to the Kremlin itself, is, "What is the state of our national film industry?" A partial answer is provided by a fleet of films in three forthcoming British festivals. And the forecast? Much darkness visible. But a rare chance to see five classic Soviet musicals from the 1930s to the 1940s on the big screen in Britain does something to brighten the picture.

Film professionals here in Moscow seem an unusually cliquey lot (unless it just goes with the territory). Certainly, the Russian cinema is highly dynastic, and if you add up all the parent-child, or brother-and-sister surnames - the Mikhalkovs, the Konchalovskys, the Germans, the Smirnovs, the Todorovskys, to name but a few - the result reads like a filmic rewriting of War and Peace.

Some of the oldies still swear that everything was better in the old (Soviet) days when production schedules were enormous, as were audiences - there wasn't much competition, after all - and the only potential demons out there were the censors. Not that there weren't pressures on film-makers back then: some of them can be seen in Igor Mayboroda's Rerberg and Tarkovsky, The Reverse Side of Stalker.

It shows the fraught experience of the brilliant cinematographer Georgy Rerberg, whose lensing was crucial to the early success of films by Tarkovsky, such as Stalker (picture left), and his contemporary Andrei Konchalovsky. Mayboroda's film catches the uneasy relation between the auteur-director and his Director of Photography, as well as much of the frustrations of the latter's subsequent career. It plays in the Sheffield Documentary Film Festival (SFF, 4-8 November); the other three events where you can catch some of the films mentioned here are the London Film Festival (LFF, 14-29 October), the Russian Film Festival (RFF, 30 October-8 November) and the Encounters International Short Film Festival (EISF 17-21 Nov).

It shows the fraught experience of the brilliant cinematographer Georgy Rerberg, whose lensing was crucial to the early success of films by Tarkovsky, such as Stalker (picture left), and his contemporary Andrei Konchalovsky. Mayboroda's film catches the uneasy relation between the auteur-director and his Director of Photography, as well as much of the frustrations of the latter's subsequent career. It plays in the Sheffield Documentary Film Festival (SFF, 4-8 November); the other three events where you can catch some of the films mentioned here are the London Film Festival (LFF, 14-29 October), the Russian Film Festival (RFF, 30 October-8 November) and the Encounters International Short Film Festival (EISF 17-21 Nov).

For the next generation, the 1990s were very lean years indeed which saw cinemas changing into car dealerships and the like, until they eventually reverted to their original condition, only for their screens to be dominated by Hollywood. That's not to say that memorable works weren't made, though more in the arthouse style than for mass consumption, and nostalgia addicts still had film festivals at which to drown their sorrows in every sense.

But the 21st century brought rapid developments for the better, like Timur Bekhmambetov's Night Watch (2004), a runaway box-office hit both locally and internationally, and the challenging but hugely popular Afghan war drama Company 9 by Fyodor Bondarchuk the following year. Andrei Zvagintsev's The Return (2003) was the flagship film of this new generation, taking the top prize at Venice that year; alas, it rather overshadowed Alexei Popogrebsky and Boris Khlebnikov's Koktebel (main picture, above), a low-key road movie concentrating on father-son relationships that, for me, remains a minor masterpiece. Credit here to its producer, Roman Borisevich, who has doggedly backed a very impressive small stable of independent works with a mixture of state money and income from buying in foreign films for local distribution.

After Koktebel, Khlebnikov and Popogrebsky went their separate ways, entirely amicably. The latter avoided the "second film" syndrome with the impressive Simple Things (2007); his third film, currently being edited, moves back from urban settings to the far flung wastes of Russia's Pacific coast. Meanwhile Khlebnikov went on to make Free Floating, a bleak but nuanced look at the landscape of provincial Russia, with its under-employment and local absurdities.

His third film, Help Gone Mad (LFF, picture right), is the story of an immigrant worker from Belarus who comes to Moscow looking for work, only to be fleeced, and then taken in by a well-meaning, but somewhat out-of-the-loop local. The events that follow are rather surreal, though Khlebnikov had loosely rehearsed them in a previous documentary. Does Help Gone Mad capture something of that mysterious entity, the Russian soul (with a chunk of Belorussian soul thrown in)? Yes, if you assume that, when all seems to have gone resoundingly wrong, there's an ending that may be a bit mad, but at least not tragic.

His third film, Help Gone Mad (LFF, picture right), is the story of an immigrant worker from Belarus who comes to Moscow looking for work, only to be fleeced, and then taken in by a well-meaning, but somewhat out-of-the-loop local. The events that follow are rather surreal, though Khlebnikov had loosely rehearsed them in a previous documentary. Does Help Gone Mad capture something of that mysterious entity, the Russian soul (with a chunk of Belorussian soul thrown in)? Yes, if you assume that, when all seems to have gone resoundingly wrong, there's an ending that may be a bit mad, but at least not tragic.

Borisevich's production entity, now named the Koktebel Film Company, is also responsible for another LFF entrant, Vasily Sigarev's screen debut Wolfy. If the title seems to have a transatlantic feelgood quality, don't be deceived: the Russian title falls between "volchok", a child's spinning top, which turns madly before falling off the table (not the most subtle analogy, but a powerful one in the film), and "volchonka", or "little wolf". There's every reason to sympathize with whoever translated the film, since they also had to contend with an almost continuous slew of "mat", the Russian slang that makes English four-letter words look like polite tea-party dialogue. Sigarev is best known in the UK for Plasticine, his stage play which, in its Royal Court production, won an Evening Standard award. For those who missed that, believe me, it doesn't come much bleaker.

Except that, yes, in Wolfy (picture left) it sure does, not least because the camerawork is often rather beautiful, making the contrast between visual image and story all the harsher. In the opening scene a pregnant woman, chased by police across fields of deep snow for a crime she has committed, goes into labour (it's surprising only that we don't actually see the birth on screen). Later, the woman, back from jail, and sleeping with practically any man who is still sober enough, gives her first present to her daughter, now around seven: a hedgehog. The girl promptly smothers it, then throws it under a passing train for good measure, almost followed by herself as well. Not to mention the graveyard scenes, with wolf cubs which appear to be shrink-wrapped in plastic.

Except that, yes, in Wolfy (picture left) it sure does, not least because the camerawork is often rather beautiful, making the contrast between visual image and story all the harsher. In the opening scene a pregnant woman, chased by police across fields of deep snow for a crime she has committed, goes into labour (it's surprising only that we don't actually see the birth on screen). Later, the woman, back from jail, and sleeping with practically any man who is still sober enough, gives her first present to her daughter, now around seven: a hedgehog. The girl promptly smothers it, then throws it under a passing train for good measure, almost followed by herself as well. Not to mention the graveyard scenes, with wolf cubs which appear to be shrink-wrapped in plastic.

There's no denying Sigarev's talent, but it's so remorseless. The only characters that show any good side are, as in Plasticine, the weak and aged grandmother, and the child who, like the child in Plasticine, meets a violent fate. I’m no moralist critically, and admit to extensive enthusiasm for the bleaker film products of the Slavic world – if they come across as justified in their examination of a wider society or particular emotional relationships. Sigarev is no moralist, either – the “-isms” he’s chosen are those of our old friends the French Marquis and Dr. Nihil. Compare the end of Wolfy with that of Koktebel, also a demanding journey in parent-child relationships. They are poles apart.

All this may leave the impression that the tone of new Russian cinema is a mix of absurdity and cruelty. And that may be true of the work that reaches the international festivals and frequently wins prizes there. It's more than balanced, however, by popular comedies, some dire, some very impressive, like Bekhmambetov's The Irony of Fate 2, the top grosser in 2007 which beat all the Hollywood product into the ground. Then there are the mainstream blockbusters, some historical, some in the thriller genre, which are strongly encouraged from on high for their patriotic motifs.

Suggestions that the Kremlin is in control of national film ideology are more than just rumour: one of the internationally most respected young directors, who will remain nameless here, told me of a conversation with a leading producer in which he learned that his proposal for a downbeat personal film about World War II would never get official approval. And so he's looking to Europe, where producers are practically queuing up to work with him. Meanwhile, the state is fully funding a nationalistic epic about the WW2 defence of the Brest fortress.

The grandmother of the "absurdity and darkness" genre is the Odessa veteran Kira Muratova, whose The Asthenic Syndrome burst on the scene back in 1990 with the impact of a broken bottle held up to the viewer's throat. She films in Russian, is supported equally by Kiev and Moscow, and in fact must be the only thing left in Russian-Ukrainian relations that still brings satisfaction on both sides of the border.

This septuagenarian director is up there with such classic arthouse directors from the Soviet era as the late Andrei Tarkovsky and Sergei Paradzhanov, as well as Alexei German Sr. (who is still working, albeit slowly and hampered by illness) and Otar Ioseliani, who has long been making films that are as much Georgian and French as Russian/Soviet. After a lean period in the 1990s, Muratova has had a hugely prolific decade with Melody for a Street Organ (RFF, picture right), her sixth feature in the Noughties. It has a humanism that hasn't been seen in her work for some time, though the surrounding lunacy hasn't gone away. And with age, her films don't come any shorter: Melody runs over two and a half hours.

This septuagenarian director is up there with such classic arthouse directors from the Soviet era as the late Andrei Tarkovsky and Sergei Paradzhanov, as well as Alexei German Sr. (who is still working, albeit slowly and hampered by illness) and Otar Ioseliani, who has long been making films that are as much Georgian and French as Russian/Soviet. After a lean period in the 1990s, Muratova has had a hugely prolific decade with Melody for a Street Organ (RFF, picture right), her sixth feature in the Noughties. It has a humanism that hasn't been seen in her work for some time, though the surrounding lunacy hasn't gone away. And with age, her films don't come any shorter: Melody runs over two and a half hours.

A sense of the absurd comes through strongly in the work of most of the new generation. Kirill Serebrennikov's Playing the Victim adapts a stage play about a central character who earns his living by re-enacting crime scenes for the police in the role of the victim. Serebrennikov, like Sigarev, comes out of a theatre background. In fact, one of his first Moscow productions was the latter's Plasticine.

Some emotional balance comes from a couple of female directors, Larisa Sadilova and Dunya Smirnova, whose work shows that not everything in Russia revolves around hallucinogenic drugs or a national shortage of Prozac; instead they address the dramas and emotional complexities of everyday life. Pavel Lungin, another relative veteran of the Russian industry, seems to have moved away from his blackish comedy style of the 1990s, as seen in Taxi Blues and Luna Park, both released in Britain. In his new film, Tsar (RFF, picture left), he turns back to Russian spiritual history in a story of conflicts between Ivan the Terrible (played by Lungin's frequent star, Pyotr Mamonov) and his religious confessor. Then there's Cannes regular Nikolai Khomeriki, who entered the Koktebel company with this year's Tale in the Darkness.

Some emotional balance comes from a couple of female directors, Larisa Sadilova and Dunya Smirnova, whose work shows that not everything in Russia revolves around hallucinogenic drugs or a national shortage of Prozac; instead they address the dramas and emotional complexities of everyday life. Pavel Lungin, another relative veteran of the Russian industry, seems to have moved away from his blackish comedy style of the 1990s, as seen in Taxi Blues and Luna Park, both released in Britain. In his new film, Tsar (RFF, picture left), he turns back to Russian spiritual history in a story of conflicts between Ivan the Terrible (played by Lungin's frequent star, Pyotr Mamonov) and his religious confessor. Then there's Cannes regular Nikolai Khomeriki, who entered the Koktebel company with this year's Tale in the Darkness.

Paper Soldier (RFF), directed by Alexei German Jr., is set in the 1960s against the backdrop of preparations for the first manned space rocket launch with the heroic Yury Gagarin, though the film is dominated by the dramas of the other people involved in the project. German Jr. keeps up the visual tradition of landscapes that could be set almost anywhere, just as long as they're practically sunless and shrouded in frequent mist. The Kazakh steppes fit in well on that front.

There's more bleakness to be found in Alexei Balabanov's Morphia (LFF). Balabanov could be called a "middle generation" director, with at least two decades of films behind him; his new work, which is absolutely back to his best standards is an adaptation of Mikhail Bulgakov's Notes of a Young Doctor, scripted, incidentally, by the late Sergei Bodrov Jr. Bodrov was one of the great white hopes of the Russian industry, both as actor and director, until his tragic death in 2002 in a landslide that engulfed the crew of the film he was then working on.

Morphia is a period piece - it's set around the 1910s - with bleached-out colour photography, endless snow scenes, an almost silent movie use of inter-cut screen titles, and considerable - very considerable - use of music from the time, particularly that of the classic crooner Alexander Vertinsky, whose songs mix decadent cabaret drollery with underlying melancholy.

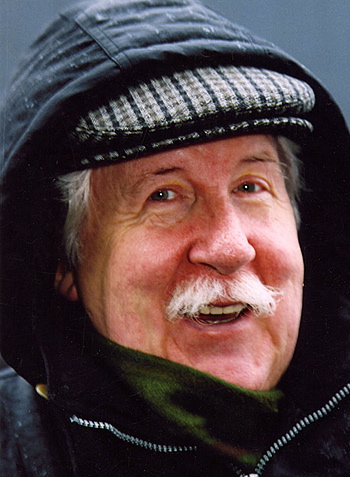

Which makes Andrei Khrzhanovsky's Room and a Half, (LFF) considerably more empathetic. The director (pictured right) is a veteran and highly respected animator, and here he turns his hand to a live-action film for the first time, albeit one with many differences from standard fare. It's the story of the poet and Nobel prize winner Joseph Brodsky, seen in his native Leningrad and particularly with his parents (masterful roles from two stage veterans, Alisa Frejndlikh and Sergei Yursky), as well as in his North American exile.

Which makes Andrei Khrzhanovsky's Room and a Half, (LFF) considerably more empathetic. The director (pictured right) is a veteran and highly respected animator, and here he turns his hand to a live-action film for the first time, albeit one with many differences from standard fare. It's the story of the poet and Nobel prize winner Joseph Brodsky, seen in his native Leningrad and particularly with his parents (masterful roles from two stage veterans, Alisa Frejndlikh and Sergei Yursky), as well as in his North American exile.

Khrzhanovsky, in a script co-written with Yury Arabov (perhaps Russia's best-known screenwriter, particularly for his long-term collaboration with Alexander Sokurov) brings in the whole gamut of visual effects, from archive footage to the restaging of events in Brodsky's life and extensive animation interludes. It's not a biography, but an impressive and poised artistic treatment of a life. The director will be present at the London Film Festival, and also at the Encounters Short Film Festival, where he will talk about his early work.

Also on view in London this month (all in the RFF) are Sergei Solovyov's long-awaited, sumptuous version of Anna Karenina and Karen Shakhnazarov's Ward 6, adapted and updated from a Chekhov story set in a lunatic asylum. Shakhnazarov has been filming steadily over the last decade or so - his position as director of Russia's main film studio Mosfilm can't have harmed that process - and his work explores some of the incidental absurdities of both history and the present day. There's also Nikolai Dostal's Pete on the Way to Heaven. Back in 1991 Dostal made a masterpiece, Cloud Heaven, that caught brilliantly the peculiar existential despair out there in the Russian sticks. In Pete, Dostal is right back at his best, this time with a story set in a military garrison in the wilds of Siberia at the very end of the Stalin era.

It's resoundingly back to the Stalin era for the RFF's sidebar of five Soviet musicals, little known outside the Slavic world, but still popular at home. This is effectively a retrospective for director Grigory Alexandrov and his star actress, and wife, Lyubov Orlova. Volga-Volga (picture left) from 1938 was apparently Stalin's favourite film. In tone they resemble quite strongly comparable Hollywood productions of the time, even if the themes were very different, and the star quality of Alexandrov and Orlova fully equalled that of their transatlantic contemporaries. Stalin himself was no film-goer; instead he had his nightly kino delivered direct to the Kremlin, where politburo colleagues would enjoy (or suffer through) all-night screenings. One wonders whether the same Kremlin screening room is still in use today.

It's resoundingly back to the Stalin era for the RFF's sidebar of five Soviet musicals, little known outside the Slavic world, but still popular at home. This is effectively a retrospective for director Grigory Alexandrov and his star actress, and wife, Lyubov Orlova. Volga-Volga (picture left) from 1938 was apparently Stalin's favourite film. In tone they resemble quite strongly comparable Hollywood productions of the time, even if the themes were very different, and the star quality of Alexandrov and Orlova fully equalled that of their transatlantic contemporaries. Stalin himself was no film-goer; instead he had his nightly kino delivered direct to the Kremlin, where politburo colleagues would enjoy (or suffer through) all-night screenings. One wonders whether the same Kremlin screening room is still in use today.

Sheffield Documentary Film Festival (4-8 November); London Film Festival (14-29 October); Russian Film Festival, London (30 October-8 November); Encounters International Short Film Festival , Bristol (17-21 November).

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Comments

...