theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Gary Numan | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Gary Numan

theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Gary Numan

The electronic music icon talks highs, lows, love, booze, Jesse Jackson, Carole Caplin, and much more

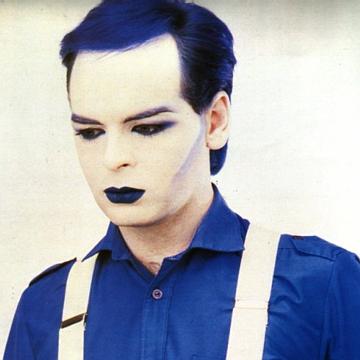

Gary Numan (born Gary Webb, 1958) was born in Hammersmith and raised in the western outskirts of London, the son of a bus driver. By the latter half of the Seventies he was fronting punk band Tubeway Army but his fortunes changed dramatically when he added synthesizers to the formula and became, with the album Replicas and songs such as “Down in the Park” and “Are ‘Friends’ Electric?”, one of electro-pop’s great innovators.

Things very slowly resuscitated after the album Sacrifice in 1994, a move into dark Gothic industrial music. At the same time a wide range of bands, from Marilyn Manson to The Prodigy, started acknowledging his influence, and acts ranging from Basement Jaxx to The Sugababes sampled his work on major hits. Many albums later, Numan is a going concern able to fill large venues and headline festivals. As well as his own recent album Dead Son Rising, he has contributed vocals to new material by Battles, Officers and Huoraton - the latter two yet to be released - and is working on a new album with the possible title Splinter. He is about to head out on tour in support of Machine Music, a DVD of his singles.

I meet Gary Numan in his large house in the Sussex countryside, greeted at the door by his flame-haired wife Gemma. We go through to a spacious living room, velveteen and dusky scarlet. Numan sits on a sofa and sips water due to a medical check-up that told him he has to drink more of it, although he says, “For such a neutral drink I find it really unpleasant.” Gemma brings us both a cup of tea. Numan was known in his youth for supercilious arrogance, although a later diagnosis of low-level Aspergers may go some way towards explaining his attitude. Today – and, indeed, every time I’ve dealt with him – he is overwhelmingly self-deprecating at the same time as occasionally cheeky and laddish. Before the dictaphone goes on, as we settle, he chats about his possible move to California later in the year, the positives and negatives, and he speaks about the possibility of doing film soundtracks in Hollywood…

THOMAS H GREEN: Is Trent Reznor a friend of yours?

GARY NUMAN: He’s become a mate. Whenever I go there we try and meet up and hang out. I don’t speak to him every day.

GARY NUMAN: He’s become a mate. Whenever I go there we try and meet up and hang out. I don’t speak to him every day.

He’s doing well with film soundtracks these days – he won an Oscar for The Social Network and he recently did David Fincher’s The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. Do you think he might give you a leg-up in that world?

It’d be nice. He works with Atticus Ross who I met when I was over there doing Nine Inch Nails' farewell shows. He’s a cool man. When I was over there in March I met up with Clint Mansell who also does a lot of film work [Black Swan, The Wrestler, Moon] and used to be in Pop Will Eat Itself. He was a brilliant bloke. I heard he was pretty reclusive and difficult to talk to but he was lovely, really entertaining. The thing that was most pleasantly surprising was when [Numan co-manager and musical collaborator] Ade [Fenton] said he was going to arrange lots of meetings I was nervous. I thought it would be demoralising, expected to go in cap in hand, but it wasn’t like that at all, most people we spoke to had seen us live.

Would film work replace concerts?

I’d like to run it alongside as I love getting on a bus and touring, I couldn’t imagine not doing it. If there was any conflict I’d take the touring but I’m 54 so how many years have I got? I’ve got to be near the end of it.

Your live following doesn’t seem to be in any danger of going anywhere.

It’s not that so much. It’s my own standards. The music I make these days and the way I perform, it's quite aggressive and angry and there’s going to come a point where I just become too old to look convincing. It’ll go from being acceptable to naff really quickly. That’s what I’m expecting. If that day doesn’t come or is a long time coming I’ll be really happy. I am brutally honest with myself about everything and I think that there’s going to be a time in the not too distant future when I’m going to be embarrassed.

You certainly smile more these days – you used to always look so stern.

For quite a long time on stage it’s been easy. All that stuff I used to be bothered about, well, all the things that can go wrong have gone wrong and it’s never as bad as you think it’s going to be. Simply by doing it for so many years you just become comfortable with it. You just aren’t at the start. I wasn’t, anyway.

So you're saying you weren’t being moody, it was just nerves. I thought maybe surly was your default setting.

That was my default setting, still is. If I’m not particularly thinking about anything I have a tendency to look a bit sullen, I’ve got a fat bottom lip which doesn’t help. I always look like I’m slightly sulking. Sometimes I am.

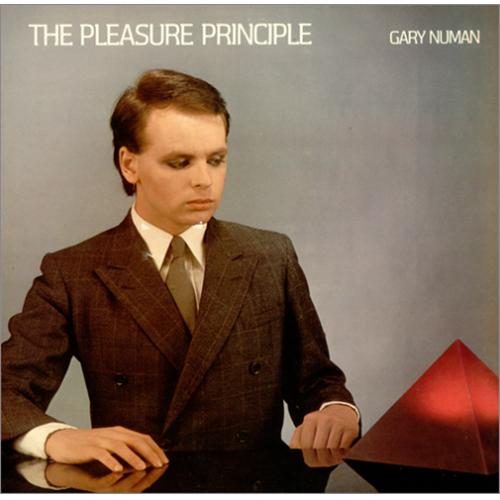

When you toured your 1979 album The Pleasure Principle in 2009, you played it electronically and then moved onto an entirely different set playing your newer industrial rock material. It was the first time I’d seen you play the old songs as they sounded originally rather than in your current style.

When you toured your 1979 album The Pleasure Principle in 2009, you played it electronically and then moved onto an entirely different set playing your newer industrial rock material. It was the first time I’d seen you play the old songs as they sounded originally rather than in your current style.

There were two reasons for wanting to do The Pleasure Principle that way. It was the 30th anniversary of that album being Number One so I wanted to do it as it was, not some rehashed heavy version. I also thought it would create a much more effective mood move from that era to what I’m doing now. It was nice to show where and how the progression has happened.

There was a large section of mostly younger fans who didn’t seem massively bothered about The Pleasure Principle but had come to hear the newer songs. Is that gratifying?

It is, in a way. It’s just a shame that it feels like there’s a slight split from people who’d much rather have the older stuff. At some point, probably the mid-Nineties, I switched to what I do now. There are people who’ve come with me but almost begrudgingly. They say all the right things but still bring along their Replicas album to get signed. I’m grateful for that because a lot of people disappeared, but it’s a shame there’s not a greater crossover from one era to the other.

Your jazz-funk direction in the Eighties must’ve been harder for your fans to swallow. In those days – to generalise wildly - the people who listened to jazz-funk in small southern English towns like the one where I grew up, were the people who, on a Saturday night, tried to kick in people who looked like you did, men who wore eyeliner.

That was probably the beginning of my first downfall really. It’s difficult to remember exactly what was going through my head. I recall being really aware I wanted to broaden myself musically, trying different styles and flavours. I never wanted to make massive changes – country and western one day, jazz the next - but I wanted it to meander fairly aggressively from one thing to another while keeping the core of what I had. I got into fretless bass, saxophone, girl singers, jazz-funky for bit, but I’m not sure it was a good thing to do. I think I lost sight of what the core of me was and became a bit lost and aimless for some time.

So you parted ways with your fans?

Most of them disappeared in 1982 anyway. I did an album called I Assassin, which was about the worst-selling album I ever had. That was still in the shadow of massive Number One albums. When that didn’t do really well it was a shock. That pretty much finished me at Beggars [Banquet – his label]. Everyone lost interest after that. Then I did another one called Warriors, which was an improved version of the one before in some respects, but by I Assassin I was already in big trouble and it was only my sixth album. When you think Replicas did 200,000, I Assassin did 22,000 - that was bad.

The drummer Cedric Sharpley, who played on some of your most famous songs throughout the Eighties, died in March. How were your relations with him?

It was really sad he died but I was sadder when I realised I hadn’t spoken to him for well over 20 years. That really bothered me. When I stopped using Cedric as the drummer I was told by someone that he was particularly peeved about that. I just carried on my life with this feeling that he was a bit unhappy with me but I never tried to do anything about it. I went to the funeral, met up with a couple of the old band members and it was just like yesterday. I regret I lost touch with him so badly. I do tend to stick with people for a long time. Cedric was with me for many, many years. I just started to feel, as I was getting older, that I needed to bring in new blood, new interpretations of songs. People who’ve been playing them for years tend to follow the same pattern, do fills at the same time and it all becomes a little bit pedestrian. The only way to fix that is get new people in. Cedric and I never fell out. He wasn’t sacked.

How did you put that band together?

How did you put that band together?

I auditioned Chris Payne on keyboards, Cedric I auditioned and Russell Bell [guitar, keyboards] I kind of auditioned but really got in because he was a mate of a mate. Since then I don’t think I’ve auditioned anybody in terms of playing. Everybody is recommended by somebody I respect. I just got a new bass player because the guitar player said, “I know someone who’s really good.” His audition was to come round here for the afternoon and see if we get on. I assume he can play because the guitar player said so and he knows what he’s talking about. So they’ve all joined that way for 20 years or more. If you’re going to be locked in a bus with people – somewhere I used to consider a stressful environment – if you’re all crammed together on the bus, you’ve got be able to get on, mates first, work partners afterwards. If anybody makes a mistake nobody gets bollocked. I make more mistakes than anyone. We always try and make it feel like a school outing with your mates. I’ve always wanted it to have that feel.

You don’t drink, do you?

I do a bit now. I got drunk in Mexico in 2010 by accident. Somebody gave me a blue drink that they said was Red Bull and it had vodka in it. I couldn’t taste the vodka and I drank four of them in half an hour and got really pissed for the first time ever in my whole life - at 52. I’d never been drunk before and I thought, that’s alright, that! Then I started trying to drink and didn’t do very well because I hate the taste of it. Then my wife had this brilliant idea. She said, “Why don’t you think of it as medicine?” Have some in a glass, get rid of it as quick as you can, then wash it down with something you like - Coca Cola or lemonade - so that’s how I do it. And I don’t get hangovers either, not even a headache. I got hammered the other night, went to see my mate’s band Sulpher at the Purple Turtle, I got a bit carried away, met up with loads of mates I hadn’t seen for ages, had a brilliant laugh… got a bit too drunk, actually.

In interviews over the last 10 or 15 years you’re very self-deprecating, almost unwilling to take credit for some of your successes. You often dismiss the breakthrough electronic sounds on your early singles, saying that the synthesiser just happened to be in the studio. Are you not proud of your achievements?

Yeah, I am, but I did find that synth by accident. I’m not proud of that - I’m proud of how quickly I saw its potential and did something about it. It wasn’t as if I’d been at home and thought, what we need is electronic music and I’m going to make it happen. I’d have been really proud of that. I’m proud of the way I used that synthesiser. There were a number of people doing it at the time, most of them before I did. I saw an interview with Andy McCluskey [of OMD] and he thought of me as this Johnny-come-lately.

There were Sheffield electronic acts who were at it for years and you suddenly exploded. Then again, The Human League’s Dare was absolutely massive just as your career started to wane. Were you jealous?

There were Sheffield electronic acts who were at it for years and you suddenly exploded. Then again, The Human League’s Dare was absolutely massive just as your career started to wane. Were you jealous?

No, I’ve never been jealous, never was as a kid. If we saw someone driving past in a beautiful car I never wanted to scratch it because I always thought, I’ll have that, not in an arrogant way, more naïve. Dare just made me think I was doing something wrong and I’d have to try harder. I’ve never been massively confident about what I do. If an album doesn’t do massively well, I don’t think my talent has gone unrecognised. I thought I was lucky to be recognised in the first place, so when things don’t go well I just put my head down and get on with it. I loved music before I was famous - that was the cake, fame was just the icing. Certain parts were a bit humiliating – seeing the attendance at shows fall from tens of thousands to a few hundred was difficult, the ego takes a bash.

Watch Gary Numan perform "Down in the Park" on The Old Grey Whistle Test

Are you as famous as you want to be now?

No, I’d like to be a bit more famous than I am.

The media generally leaves you alone these days but there was a small outbreak of controversy last year when all the papers round here [in Sussex] reported that you were going to America to escape rural “yobs”.

I did an interview with The Daily Record in Scotland and as it was winding down I talked with the guy about kids, mentioned moving to America which then became the theme of the write-up. That then got picked up by lots of people who never spoke to me and just rewrote that article, getting it completely wrong. Every time a new version came out, a few more untruths had been added. Apparently my wife was attacked by yobs in the local high street. What really happened was she was walking down the high street with my children and a group of about half a dozen lads, anywhere from about 12 to 14, were following her going, “Ooh, I’d fucking give you one.” My wife turned round and said, “Alright, who’s first?” and they ran away. That was it but it’s not quite the way it was reported.

The thrust of the reports I read was that you were making out rustic English villages were more dangerous than South Central, Los Angeles.

We’ve been in this process [of moving to the States] for two years, long before that episode, long before the riots in London. It takes a long time to get a green card. One of the problems I do have with this country – although it’s not why I’m leaving – is that thug culture seems to be spreading, much worse than when I was a kid. Even in the middle of nowhere you do get gangs of lads loitering on the corners being a bit of an arse, shouting things – but it’s nothing like gang warfare in the States.

Lemmy says of “Ace of Spades” – his signature song - that it no longer gives him pleasure but he plays it for the fans. Is that how you feel about “Cars”?

It was. I went through that. For about three years I wouldn’t play “Cars” live and then I thought, that’s arrogant, that’s ignorant, so I got over that and started playing it again, but didn’t really enjoy it. Recently, in the last five years or so, I’ve come to appreciate… not the song particularly – it’s a pretty average song – but what it’s done. It’s one of the most famous songs ever. That’s quite a cool thing to have done so I have a much more favourable relationship with it than before. I feel really proud that I wrote something that successful. I’ve gone full circle with it. I also always had a problem perfoming "Cars" because it’s three or four minutes long and all the singing happens in the first minute. After that what do I do? Stand around looking interested? I used to sit on the side of the stage and watch the band but doing it on TV is a nightmare. You just have to stand there.

Do you have a favourite of your promo videos?

“We Are Glass” I like a lot. I’m proud of the “Cars” one. I’ve made some honkers over the years. I’ve a very poor track record. Recently it’s been OK and it wasn’t too bad at the beginning but the middle years – fucking rubbish.

Watch the video for "We Are Glass"

Isn’t it just like looking at old photos where people see themselves dressed in clothes that have long gone out of fashion?

No, some of it’s pretty cringe-worthy, to be honest. I accept it’s all a part of what makes me what I’ve become, even the bad ones. At the time I was pretty keen on them so hands up as guilty but putting a music DVD together, as we have been, some of that was a bit hard.

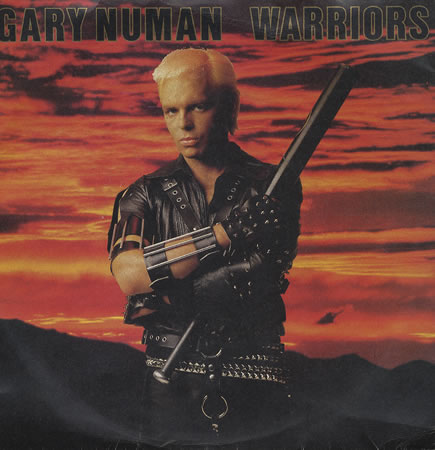

Your Mad Max image for Warriors was one that received a lot of flak. The first two Mad Max films are great but that image just seemed to have no relevance to the music.

Your Mad Max image for Warriors was one that received a lot of flak. The first two Mad Max films are great but that image just seemed to have no relevance to the music.

That’s where I went wrong, you see, because when I started I used to think of it as machinery and all the parts had to go in the right direction - how you looked, what you talked about, the covers, the music, all had to compliment each other. The image was a vital part of that. Within two or three years I lost track of that and started to change image just for the sake of it. Each image had to be completely different from the one before but they no longer had any relationship with the music. You couldn’t look at the image and know what you were going to listen to. I started to lose the plot. I was very together when I started. I was very lucky but I did have all the right pieces in the right places. The whole fame thing happens and you lose sight of things somehow. As soon as you get in the middle of it, you drown in it and lose your common sense.

What were you thinking of when you covered Prince’s “U Got the Look” in 1992?

That was Miles Copeland. I just signed to his label [IRS] and it was suggested that if I wanted them to be helpful and cooperative in terms of marketing budgets I really did need to do what I was told. What they wanted me to do was that song [sings] “I was born one morning when the sun didn’t shine” [“Sixteen Tons” by Tennessee Ernie Ford] or “The Letter” [by The Boxtops], old Sixties shit which I hated with a passion. So it was a compromise. I didn’t have to do that shit but I do a Prince track or something else Miles Copeland thought was cool at that moment. But there’s still no excuse. What I should have said, was, “Bollocks, I’m not fucking doing that and I’m not doing that either, and you can stick your promotional budget up your arse.” That’s what I’d have said in ‘79 and that’s what I’d say now. But my career was in trouble, I was running out of money, I had all kinds of debts, and he seemed like a lifeline. More than that he seemed like he might open up America again and so I… [mutters quickly] sold my soul. Funny actually, when you first become successful people say you’ve sold out - not true, you sell out in moments like that, later on; you sell out trying to keep it, not get it. I did anyway. Replicas, my first big album, I didn’t write any of those songs thinking I was going to be a pop star, yet I remember getting quite a lot of criticism at the time, saying I’d sold out. No I haven’t - I’ve made an album in my mum’s front room that’s captured a moment. I later sold out many times – "U Got the Look" was probably the worst one.

Surely selling out – the idea of authenticity in pop music – is a bit irrelevant, a bit sidelined these days?

I get it, the selling-out thing. If you make an album and the only reason for making it is because you love every bit of music on it, that’s cool, doesn’t matter if it sells 100 million copies. If you do a song simply to try and improve your career or make money, then you’ve sold out, there’s no integrity in that whatsoever… shameful.

Have you ever been to see Brock and the Badgers – the pub blues band that’s the current home to your original drummer and uncle, Jess Lidyard?

No, I never have. I should have done. I haven’t seen him for about three years. I used to see him at Christmas but now we have kids Christmas has evolved into our own thing.

He recorded Replicas with you but decided not to stay in the band.

I said to him, when we were getting a band together before Replicas was successful, “We’re going to tour this at club level, do you want to be in the band properly?” But he didn’t because he had a really good job, working for Avis, the car hire company, and didn’t want to risk it, said he’d done the touring thing when he was younger.

Did he ever regret that decision?

He never said so. I hope not. There must be a twinge once in a while when you see what we went on to do.

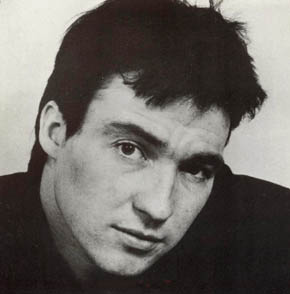

You still regularly pay tribute at your concerts to the other member of that band, the late Paul Gardiner (pictured right). You even once wrote a song, “A Child With the Ghost”, about him. Why is he still so important to you 28 years after his death [from a heroin overdose]?

You still regularly pay tribute at your concerts to the other member of that band, the late Paul Gardiner (pictured right). You even once wrote a song, “A Child With the Ghost”, about him. Why is he still so important to you 28 years after his death [from a heroin overdose]?

I joined his band. He had a band called The Lazers and they were looking for a rhythm guitar player. It was mainly him that got me in. I had a good rapport with him from the beginning. I don’t think the other two were that keen on me but he was really keen. Then the first rehearsal we ever did I mentioned that we were called The Lazers but everyone was called “the” something. I had all these different names so we chose Tubeway Army from my list. Paul was the singer and they were only doing cover versions so I said, “You really need to be doing your own stuff.” They said, “We don’t write songs,” and I said, “Well, I’ve got shitloads.” So I played them some of my songs and Paul said, “I can’t sing these, they’re too high.” So at my first rehearsal I went from being guitar player to singer. I owe him a debt. His support and enthusiasm for what I was doing started then and lasted right until the day he died. He was always right there backing me up whatever I wanted to do. Stopping doing punk and moving into electronic I couldn’t have had a better ally. Meeting with Beggars Banquet, they didn’t want to put out an electronic album and I’m standing up getting all silly - Paul was right there. It was Paul who got us the original deal with Beggars. Everything that happened to me, he was there doing the legwork.

Did he become psychologically lost at some point?

He got into heroin and kind of lost himself. We tried really hard with him. I got him on stage on the Warriors tour and the fans went mental. I said to him then, “As soon as you’re fixed, you’re back.” He always knew that and I always told him that. I got him down to the studio to play, to keep him involved. That’s when I realised how bad he was. He was playing a song then he just passed out, fell forward onto a big old Trident desk, collapsed. He got wedged in, we couldn’t move him, just left him there and had to work round him. He was just gone with his bass in his hand, then he’d wake up and start playing and couldn’t figure out where the track had gone. Fucking hell, man, he was in a bad way.

It must have been a terrible time.

I knew he was in trouble. The relationship he was in then, he’d come out the door to go to rehearsals and then one of his windows would come flying out behind him, followed by her wedding ring. The pressure that she put on him was just unbelievable. She tried to get off with me in front of him once. She was a fucking arse. He was not cut out for the music business. A lot of it just slides off my back, I’m blinkered and focused, people can say all this shit and I can just get on with it. He wasn’t like that, everything hurt him really badly. You’ve got someone like that surrounded by druggy people and a wife like that – he was doomed. We were in New Zealand once and we were in this hotel. I went past his room after a gig and we were going to go down to the bar and he was on the phone to his wife. About an hour later he still hadn’t come down so I went to check and he was still on the phone and she was giving it all that. I went back another hour or so later and he was asleep on the bed with the phone in his hand and she was still having a go. What a bitch! I felt so sorry for his mum and dad – they were brilliant.

Do you recall Carole Caplin from her days in Shock (pictured left), the new romantic performance art outfit that you had something to do with?

Do you recall Carole Caplin from her days in Shock (pictured left), the new romantic performance art outfit that you had something to do with?

They supported me at Wembley [on the 1981 "Farewell” concerts, prior to Numan’s proposed "retirement”]. I saw their picture and started hanging out with them. I loved what they did, they really added a lot to the Wembley shows. I had a row with their manager who was a fucking arse. He started telling me how big their name should be on the billboard at Wembley – fuck off! What a wanker! We fell out. Idiot!

Were you surprised to see Caplin in the papers years later with the “Cheriegate” scandal?

I was a bit. I didn’t know what happened to them after Wembley. I saw her for a little bit.

You saw her? She was with you?

Not really… once or twice… was it once? Once or twice. I didn’t really see much of them after that. Lost touch with them. I did a tour with Tik & Tok [robot dancing mime duo, also in Shock], six weeks, 40 shows. Lost touch with them as well. Well, very infrequent emails. Nothing from Carole.

How did you feel about your adoption by The Mighty Boosh?

I’ve become really grateful. When it first started I loved it - really funny and so many people talked to me about it. But I honestly thought it was going to have a sting in the tail. I thought at some point in the series they’re going to come out and mock me mercilessly and it’d be horrible so I dreaded every episode. But it didn’t happen. I went to see them live when they played Brighton, went backstage and they were lovely. Noel had a Tubeway Army badge. It was actually all genuine so I was blown away. I do interviews all over the world and if there’s one common thread it’s The Mighty Boosh. In Australia it was all they wanted to talk about. For a while anyone under 25 only knew me because of Boosh.

Watch the Numan gag on The Mighty Boosh

Didn’t you appear in an episode?

Yes, I was in a cupboard for the whole of it.

The Liverpudlian DJ and producer Ade Fenton has become a close associate of yours - co-manager and musical collaborator.

The Liverpudlian DJ and producer Ade Fenton has become a close associate of yours - co-manager and musical collaborator.

He was a mate and techno DJ. I’d hate it and say, “Don’t bring any of that techno shit if you come to my house.” One day he brought some songs that were – in his own words – proper music. His production skills became better and better. I gave him one of my new songs and it came back really good. Then I said, “If you’re up for it, let’s do the whole album together.” That was Jagged, quite a few years ago [2006], and that worked out really well, brought us closer together. Then I got him in the band. He was reluctant but he looks great on stage.

Your new album is Dead Son Rising yet the song on the album is called “Dead Sun Rising”. Why?

Ade co-wrote that album, the first co-written album I’ve ever done. The song is "Dead Sun Rising" about an apocalyptic future. The album was called Resurrection but Ade and Steve [Malins – co-manager/biographer] said, “You can’t have anything more to do with religion, you’ve done that now. Any connection with religion is banned.” Dead Son Rising means the same as Resurrection but I sneaked it through. Steve did notice it but he still let me have it.

Listen to "Dead Sun Rising"

It’s true that for a long time, due to themes on a good few of your albums, every interviewer asked you questions about religion as if you were Richard Dawkins.

It was a really big thing for me. It still is. I’m very, very fiercely anti-religious. There’s not a molecule in my body that believes in anything divine whatsoever. And it is a fantastically visual subject. You put pen to paper and there’s so much to write about. It’s a real temptation. I was writing one today. I know I’m not allowed to have them but I banged out a couple of God verses – piece of piss. Printed it all out then spent the next two or three hours trying to find something that had the same flow but wasn’t anything to do with religion.

Do you sneer at people who go to church?

I’m perfectly happy if people get comfort from it. Good luck to them. I don’t believe what they believe and am shocked by how many people do, but if it brings you comfort – fine. Just don’t try to convert me.

Who’d try and convert Gary Numan?

I used to get it. I was once on an aeroplane with Jesse Jackson and he tried to convert me for the whole flight… 1980 or so. Everything I’d come back with he’d answer me with clichés – “The Lord works in mysterious ways” – that’s not a fucking answer.

Is it true some of the songs on Dead Son Rising are based on a science-fiction book you’re working on?

Science fantasy [which means] there ‘s a total lack of technology. I would like to see my days out writing. At the moment it’s just a silly dream. I write endless notes. Sometimes I get the odd paragraph, mostly snippets, very rough outlines and crude ideas.

Any idea of the structure?

It’s going to be a quest-type story. I really like Steven Erikson. He’s written 10 epic books about the Malazan Empire where there are demons and multiple gods, magic is real, and it’s unbelievably savage, truly horrific things happen. If you were to sit down for the next 10 years and write about every culture you could think of, that’s how many there are, from continent to continent, I love them to bits. They’re really hard work because he never explains, he never sets the scene, he starts in the middle of chaos. I read every night for an hour and it takes me months to read one of them.

You’ve known your wife Gemma since she was quite young.

You’ve known your wife Gemma since she was quite young.

I met her when she was 11, apparently. I think she was allowed to go to Wembley in ’81. Later, when she grew up and was a bit more womanly, I used to notice her at shows, always at the front, really good looking. The crew used to call her Fantasy Tits, very childish. The thing I used to notice was that after shows she’d come up and get stuff signed but she’d never once groupie about and do any of that shit. Although that was disappointing I was always quite touched by that. She was really cool, a cool person. We met because on one particular tour - she was in her twenties by this time - she wasn’t there, then right near the end of the tour she suddenly turned up. When she came to get an autograph that night I actually had a proper conversation with her for the first time ever. I said, “Where have you been? I haven’t seen you for ages.” She said that her mum was dying, her mum had cancer, she’d chosen to stay with her in the hospital and her dad had told her to come out this evening to give her a break from it. We ended up talking for about an hour. Even in that one conversation I thought she was brilliant. Then I didn’t see her for ages but heard her mum had died and I was doing a radio show up in Shropshire and rang her and said, “Look I’m doing this, it’s a really long drive, I know what’s happened to you – do you want to come along? Help me out?” She did. In the car, four hours there, four hours back, I realised that I’d never met anyone like her. She’s got the most amazing personality of anyone ever. We started to see each other. She knew all my anecdotes because she’d read everything. It grounded me, back to square one, start as a normal person. The only weird thing with going out with someone that’s a fan is it’s impossible to live up to their expectations. You’re inevitably shorter than they think you’re going to be, inevitably not as good in bed as they think you’re going to be, and all that. You fart and do things pop stars don’t do. On every level you’re not as much as they thought. So you have to start again. The poster on the wall looks immaculate and you don’t in real life at all.

She seems to have been hugely influential on your music and career.

We hooked up in ’92 and she’s been the most vital cog by far. So much of what’s going on now is to do with me finding a new attitude and confidence in myself. I had a really bad opinion of myself for a long, long time. I thought my guitar playing was shit, my singing was shit, my songs were average at best. Gemma, through a lot of arguments where I kicked and screamed, made me understand that I’m never going to be the best guitar player in the world but I had something - the way I sing, I should be proud of that. That was a fundamental change of attitude. I went back into the studio and made an album on my own, Sacrifice. It was the first time in many years I really enjoyed it. The music was much heavier and darker than I’d ever done. She doesn’t have a hand in the music but she has a massive hand in creating the confidence and personality. If she hadn’t been there I’d never have had the renaissance that I’ve had. But she’s a shit host. Did she only make you one cup of tea? GEMMA!

Watch the video for "Cars"

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Fevereaten sees gothic punk-metallers Witch Fever revel in atmospheric paganist raging

Second album from heavy-riffing quartet expands sonically on their debut

Fevereaten sees gothic punk-metallers Witch Fever revel in atmospheric paganist raging

Second album from heavy-riffing quartet expands sonically on their debut

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Yazmin Lacey confirms her place in a vital soul movement with 'Teal Dreams'

Intimacy and rich poetry on UK soul star's second LP

Yazmin Lacey confirms her place in a vital soul movement with 'Teal Dreams'

Intimacy and rich poetry on UK soul star's second LP

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Comments

This is the best interview

ditto TheChameleon, great

I have musically grown up

This was the BEST interview I

Top interview, even now in