Exploring Tom Crean, Antarctic Hero | reviews, news & interviews

Exploring Tom Crean, Antarctic Hero

Exploring Tom Crean, Antarctic Hero

Less well known than Scott or Shackleton, but he's the star of a one-man play

The tiny Kussuluk airport, halfway up the jagged eastern coast of Greenland, caters mostly for intrepid climbers. Like all airports it sells mementoes and knick-knacks that nobody needs, including in this case a set of classic polar pipes. No matter that it’s the pole at the other end of the Earth they’re talking about. The pipes are named after famous explorers: the Scott, the Amundsen, the Shackleton and - a good one, this, for Antarctic trainspotters - the Crean.

Crean was an Irish sailor who was the only witness to all the great iconic quests of the Heroic Age which loom so large in our national imagination. Indeed, he spent more time in the south than any other man: he was on Captain Scott’s Discovery Expedition (1901-04), then again on Scott’s fateful Terra Nova Expedition (1910-13), and finally joined Shackleton’s epic journey of survival on the Endurance (1914-16). But he didn't keep a diary – none of the ordinary seamen did, while most of the officers wrote journals or at least letters. So although he would eventually pen the odd letter, the record of Crean's part in the glorious, frostbitten soap opera has come down to us through the eyes and ears of others – principally Scott’s journal, Shackleton’s memoir and Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s polar classic, The Worst Journey in the World.

We also know what he looks like because he was photographed by Herbert Ponting on the Terra Nova expedition and Frank Hurley on the Endurance. In Hurley's best-known picture of him, he cradles some of the husky puppies born on the Endurance (all of them would meet a miserable end). The statue of Crean (pictured right) which stands in the village of Annascaul where he settled on the Dingle peninsula commemorates this famous image.

We also know what he looks like because he was photographed by Herbert Ponting on the Terra Nova expedition and Frank Hurley on the Endurance. In Hurley's best-known picture of him, he cradles some of the husky puppies born on the Endurance (all of them would meet a miserable end). The statue of Crean (pictured right) which stands in the village of Annascaul where he settled on the Dingle peninsula commemorates this famous image.

But these days Crean is speaking for himself thanks to a one-man play called Tom Crean - Antarctic Explorer, written and performed by Irish actor Aidan Dooley. It has already picked up praise all over the world, and now Crean is manhauling his sledge and setting up his tent into the Waterloo East Theatre in London.

The fact that Crean was a modest, taciturn man makes him even more inaudible to history. But, argues Dooley, there’s a more specific reason why he kept quiet. After he returned home from his third and last trip to the great white south he found an Ireland increasingly in foment. “He returned to the new country that was known as the Free State of Ireland,” says Dooley. “British soldiers and sailors were almost called traitors - his brother was shot in the back by the IRA as he was a policeman. It was not a place to speak openly about your time with a British icon. He was quiet because he had to be.”

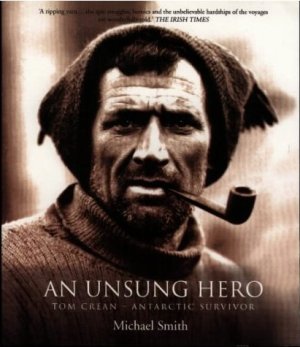

Dooley, who originally created the play for the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich in 2008, works only within the known facts. For the full story, much the best book is Michael Smith's 2000 biography An Unsung Hero (pictured below). But to summarise, Crean was born in 1877 and joined the Royal Navy at 15. He had reached the rank of Petty Officer and been demoted again by the time in 1901 his ship docked in Lyttelton in the South Island of New Zealand alongside the Discovery. An urgent replacement was needed by Captain Scott and Crean put his hand up.

He was the perfect candidate for the Antarctic life, having a vast capacity for work and for cheerfulness in the face of extreme hardship. It can be legitimately argued that if, 12 years later, Scott had selected him for the final polar party instead of the burly but ageing Taff Evans, history may well have served up a very different outcome. Crean wept as he watched Scott, Wilson, Bowers, Oates and Evans set off on the last push to 90-degrees south. Returning to the base hundreds of miles away, it was Crean’s selfless heroics which ensured that Scott’s debilitated second-in-command did not die of scurvy when they were stranded miles from safety with almost no supplies left. In blistering cold, Crean walked for 18 hours to reach help. “So it fell to my lot to do the 30 miles for help,” he wrote in a rare letter, “and only a couple of biscuits and a stick of chocolate to do it. Well, sir, I was very weak when I reached the hut.”

He was the perfect candidate for the Antarctic life, having a vast capacity for work and for cheerfulness in the face of extreme hardship. It can be legitimately argued that if, 12 years later, Scott had selected him for the final polar party instead of the burly but ageing Taff Evans, history may well have served up a very different outcome. Crean wept as he watched Scott, Wilson, Bowers, Oates and Evans set off on the last push to 90-degrees south. Returning to the base hundreds of miles away, it was Crean’s selfless heroics which ensured that Scott’s debilitated second-in-command did not die of scurvy when they were stranded miles from safety with almost no supplies left. In blistering cold, Crean walked for 18 hours to reach help. “So it fell to my lot to do the 30 miles for help,” he wrote in a rare letter, “and only a couple of biscuits and a stick of chocolate to do it. Well, sir, I was very weak when I reached the hut.”

And then on the Endurance expedition, he took an even more central role. The expedition was nominally a disastrous failure. The ship was crushed in ice floes and the large party made their way to a remote island from which six including Crean set out on a modest lifeboat to cross 800 miles of the turbulent South Atlantic to South Georgia. To reach the whaling station on the other side of the island, Shackleton picked his two most trusted colleagues to accompany him over the unmapped inland mountain range, riven by crevasses and peaks. The 22-mile crossing took them 36 hours. At one point they were forced to slide down a precipitous slope of 1500 feet. “We seemed to shoot into space,” Worsley wrote afterwards. “For a moment my hair fairly stood on end. Then quite suddenly I felt a glow, and knew that I was grinning! I was actually enjoying it… I yelled with excitement, and found that Shackleton and Crean were yelling too.”

History would not hear Crean make a louder noise. So where precisely is the source of his dramatic appeal? According to Dooley, Crean’s testimony offers “the essence of death and our desire for life, camaraderie, friendship and, most of all, altruism. The blow-by-blow details are epic, on the level of Greek myth”. And yet such is his gift for self-effacement that Crean at the same time contrives to make himself appear intensely average: our man in the south.

“I believe we see ourselves in him,” says Dooley. “We see how we would like to think we could behave if we found ourselves in the situations he did. He is the ordinary man who can tell the stories in a way we strongly relate to. Scott and Shackleton went to the proverbial moon of their day. Why? How? What was it like? Tom can answer the questions.”

“I believe we see ourselves in him,” says Dooley. “We see how we would like to think we could behave if we found ourselves in the situations he did. He is the ordinary man who can tell the stories in a way we strongly relate to. Scott and Shackleton went to the proverbial moon of their day. Why? How? What was it like? Tom can answer the questions.”

As the only man to have seen both Scott and Shackleton on the great expeditions which define their legacy, Crean is also perfectly positioned to adjudicate in the eternal debate about the relative merits of the two men. Scott’s posthumous reputation was immensely high until long after the Second World War, and only really started to plummet in the stock market of polar heroism after Roland Huntford famously debunked him in his 1979 book, Scott and Amundsen. A new boom in polar writing in the 1990s was occasioned partly by the rise of the Shackleton industry: his achievement in bringing his entire party home – undervalued in 1916 in the midst of the worst war in history – acquired more cachet as glorious sacrifice came, after decades of peace, to be a less useful and relevant example than stubborn survival. Suddenly there was a debate about which Edwardian explorer you’d rather be led up a blind alley by: the one who died (but could write his way to immortality), or the one who survived (but used ghostwriters)? Not that Dooley sits in judgment in the way he tells the story. “The audience makes up their own minds. Tom himself never said a bad word about decisions that Captain Scott made, decisions that some revisionist historians sell books 100 years later about. It’s very easy to look back and devalue the man. If Tom Crean didn't then I believe it's not my place to, so I don't.” When Scott’s body was found along with those of Wilson and Bowers, Crean said he had “lost a friend”. He was awarded with the Albert Medal by George V at Buckingham Palace, spent the war in Chatham docks and left the Navy in 1919. Having started a family, he turned down an offer from Shackleton to go south again in 1921 (Shackleton died of a heart attack in South Georgia).

Not that Dooley sits in judgment in the way he tells the story. “The audience makes up their own minds. Tom himself never said a bad word about decisions that Captain Scott made, decisions that some revisionist historians sell books 100 years later about. It’s very easy to look back and devalue the man. If Tom Crean didn't then I believe it's not my place to, so I don't.” When Scott’s body was found along with those of Wilson and Bowers, Crean said he had “lost a friend”. He was awarded with the Albert Medal by George V at Buckingham Palace, spent the war in Chatham docks and left the Navy in 1919. Having started a family, he turned down an offer from Shackleton to go south again in 1921 (Shackleton died of a heart attack in South Georgia).

When Crean opened a pub in County Kerry (pictured above) he commemorated the many years spent in Antarctica by calling it the South Pole Inn. He kept his mouth shut until his death at 61 in 1938. With his one-man play which has been seen by more than a quarter of a million people, Dooley has opened it again.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

Born with Teeth, Wyndham's Theatre review - electric sparring match between Shakespeare and Marlowe

Rival Elizabethan playwrights in an up-to-the-minute encounter

Born with Teeth, Wyndham's Theatre review - electric sparring match between Shakespeare and Marlowe

Rival Elizabethan playwrights in an up-to-the-minute encounter

Comments

...

...