Mantegna to Matisse: Master Drawings, Courtauld Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Mantegna to Matisse: Master Drawings, Courtauld Gallery

Mantegna to Matisse: Master Drawings, Courtauld Gallery

The superstars of art history flaunt their virtuosity in a series of remarkable drawings

They’re all here - well, most of them - the superstars of official art history. You would never get all these artists in one show if it were a painting exhibition, and it’s thrilling to see them cheek-by-jowl on the gallery walls. Drawing is widely seen as a secondary art, relegated to preparation and research for bigger works. So, of course, the majority of works in the show are studies for bigger projects from paintings to architecture.

As such, Mantegna’s tormented Christ is rendered over and over on both sides of the paper, hunched in pain as the artist attempts to balance human suffering and divine heroism (Studies for Christ at the Column (c.1460)). But there are drawings here that are revered works in themselves. Michelangelo's allegorical The Dream (Il Sogno, 1533, pictured below) is one such standalone piece, produced as a gift for a friend and titled by his biographer, Giorgio Vasari. It is one of the earliest examples of a standalone drawing and one of the best.

While drawing is in practice a secondary form, it is by no means secondary for the viewer, rather it brings a different set of intrinsic pleasures which this show mines deeply. We have here the unmediated hand of the master; intimate and raw marks without layers or glazes, and nothing of the studio assistants’ hand. Drawing here offers up its unique formal attributes in a succession of exemplary pieces. Movement and deftness is a recurring sensation in the details, in the tiny horse and cart in Van Gogh’s A Tile Factory (1888) where the fleet gait of the horse and the broken, uneven line of the rider’s mid-air whiplash contrast with the typically thick and spiky hatchings that set the scene. It’s remarkable what can be achieved with such limited means. Rembrandt’s fluid and dense curling lines confer weight in his figures’ clothing while light nib scratches adorn the lit faces of his Two Men in Discussion, One in Oriental Dress (1641). In Toulouse-Lautrec’s Au Lit (c.1896) a sparse jumble of lines map bed sheets and compact into a woman’s head gazing towards us. It feels intrusive to look back at her, such is drawings’ capacity for powerful immediacy.

While drawing is in practice a secondary form, it is by no means secondary for the viewer, rather it brings a different set of intrinsic pleasures which this show mines deeply. We have here the unmediated hand of the master; intimate and raw marks without layers or glazes, and nothing of the studio assistants’ hand. Drawing here offers up its unique formal attributes in a succession of exemplary pieces. Movement and deftness is a recurring sensation in the details, in the tiny horse and cart in Van Gogh’s A Tile Factory (1888) where the fleet gait of the horse and the broken, uneven line of the rider’s mid-air whiplash contrast with the typically thick and spiky hatchings that set the scene. It’s remarkable what can be achieved with such limited means. Rembrandt’s fluid and dense curling lines confer weight in his figures’ clothing while light nib scratches adorn the lit faces of his Two Men in Discussion, One in Oriental Dress (1641). In Toulouse-Lautrec’s Au Lit (c.1896) a sparse jumble of lines map bed sheets and compact into a woman’s head gazing towards us. It feels intrusive to look back at her, such is drawings’ capacity for powerful immediacy.

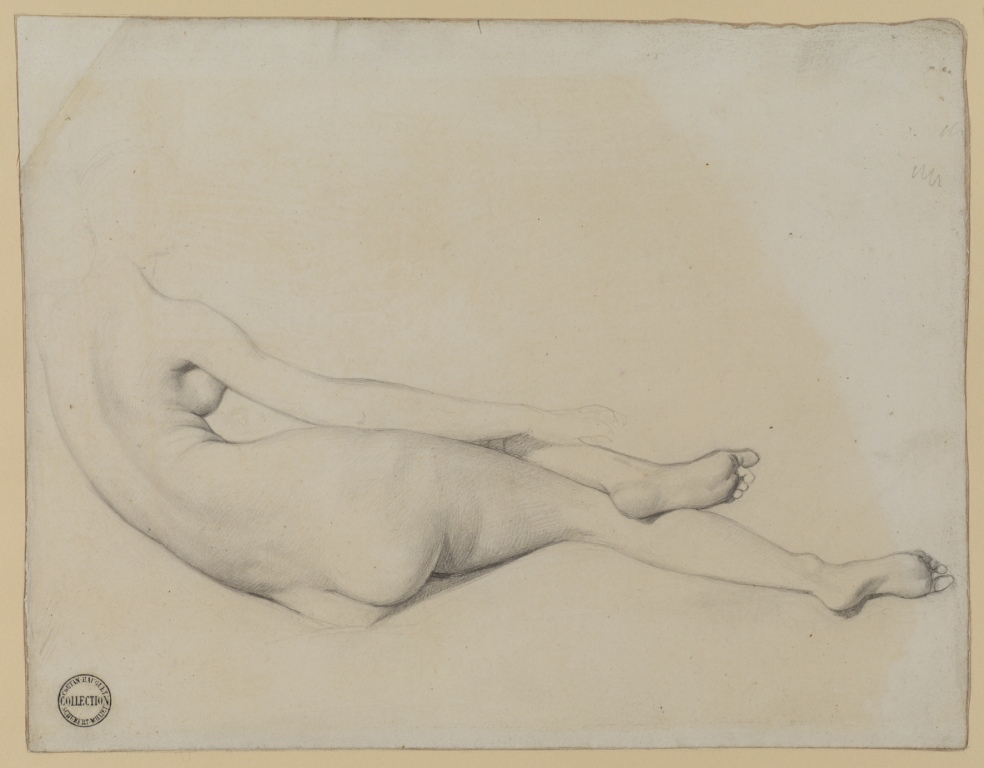

As obvious as it would seem, it’s still surprising how much some of these drawings resemble their makers’ paintings. The spikey Van Gogh is a case in point, as is Manet’s La Toilette (1860) with its frontally lit hard-edged realism, and the light and precise lines of Ingres’s study for La Grande Odalisque (pictured below, 1814). Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s expansive Kermesse at Hoboken (1559) is unmistakable and a joy to behold in its compacted intricacy, depicting scores of peasants in the drunken throes of festival.

For a relatively small show you feel exhausted by the end of it, there’s so much variety and neck-cranking detail. This is the minds of masters at work in the scribbles, revisions and erasures, unfettered by decency (there’s sex here, and some defecating) and realism. Your feelings of reverence hold you in rapt and up-close attention from picture to picture. The minutiae have a gravitational pull. Gangs of viewers huddle here and there, wincing into the spectral skeins of palimpsests and seeking out the blurry smudges of the master’s hand that give all these pictures a relic-like aura.

For a relatively small show you feel exhausted by the end of it, there’s so much variety and neck-cranking detail. This is the minds of masters at work in the scribbles, revisions and erasures, unfettered by decency (there’s sex here, and some defecating) and realism. Your feelings of reverence hold you in rapt and up-close attention from picture to picture. The minutiae have a gravitational pull. Gangs of viewers huddle here and there, wincing into the spectral skeins of palimpsests and seeking out the blurry smudges of the master’s hand that give all these pictures a relic-like aura.

Is there a downside to all this? There could be. Curatorially we have the art equivalent of watching the Harlem Globetrotters: nothing but virtuosity and it’s all in a simple chronological package. There’s no surprises, no major discoveries nor are there challenges. But for many, curators interfere too much anyway. We have a terrific parade of works here, only a few disappointments (a mediocre Picasso is one), it feels like a privilege to be among them.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment