In a Better World | reviews, news & interviews

In a Better World

In a Better World

Powerful Scandinavian drama examines the rights and wrongs of violence

It is easy to see why Danish director Susanne Bier’s latest movie would have scooped up all the Foreign Language gongs, made the festival selection lists and generally five-starred it all over the shop.

Elias’s father Anton - Mikael Persbrandt: an excellent performance - is a doctor in the geographically imprecise aid camp (malaria, warlords, Arabic-speakers – throw a dart at the map). He is optimistic and hard-working, but the work is taking its toll. Back home, his estranged wife, Marianne (Trine Dyrholm, pictured below with Persbrandt), is worried about their son’s social situation, but frankly not doing much more about it than her absent husband.

Cue the arrival of Christian (perhaps we should not read too much into this common Danish moniker, but I couldn’t help thinking that Bier could have renamed her character if she wasn’t trying to make a point), recently motherless and hurting, who instinctively sticks up for his newfound pal – more, it seems, out of a basic sense of right and wrong than because they’re friends – and inevitably takes a beating on his behalf. The next day Christian comes back on the bully tenfold, with a bike pump and a knife. Things spiral from there.

The strength and tension of Anders Thomas Jensen’s screenplay derive from healthy doses of grey between the white and the black sections of the story (and variously flawed and human responses to all that grey); but the main thrust is that a childhood/world potentially ruined by the cycle (or spiral) of violence, a boy taking matters into his own hands, going off on a vengeance spree and (spoiler alert!) becoming a car bomber is, y’know… not good.

The strength and tension of Anders Thomas Jensen’s screenplay derive from healthy doses of grey between the white and the black sections of the story (and variously flawed and human responses to all that grey); but the main thrust is that a childhood/world potentially ruined by the cycle (or spiral) of violence, a boy taking matters into his own hands, going off on a vengeance spree and (spoiler alert!) becoming a car bomber is, y’know… not good.

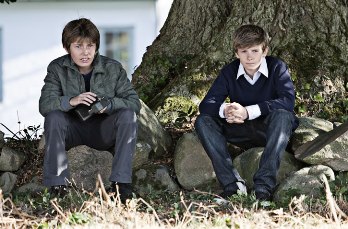

Bier’s quiet, clean movie-making is aided and abetted by some neat touches. Anton’s tattoos, which suggest he was perhaps not always a peacenik; white preppy kids using the internet to research bomb-making techniques; even occasional levity – the playground ruck has no sooner been broken up and the boys (pictured below) told to shake hands than they are asked what project they’re working on this week: "We’re in the weapons group!" says one, cheerily.

As an interrogation – so to speak – of the veneer of civilisation that separates the modern world from its grimmer prototypes, the timing of the film’s release should be discomfiting for Scandinavians and Brits alike. But, though the clue is kind of in the title, In a Better World is far from preachy, and does very well to steer clear of geopolitical specifics and stick to demonstrating the poisonous nature of violence per se. It was a particular relief to see a policeman ask the boys pointedly if there were "any other people" involved in their bomb plot – ie, the sort of people who might disapprove of cartoons of the Prophet – and to see him shrugged off.

As an interrogation – so to speak – of the veneer of civilisation that separates the modern world from its grimmer prototypes, the timing of the film’s release should be discomfiting for Scandinavians and Brits alike. But, though the clue is kind of in the title, In a Better World is far from preachy, and does very well to steer clear of geopolitical specifics and stick to demonstrating the poisonous nature of violence per se. It was a particular relief to see a policeman ask the boys pointedly if there were "any other people" involved in their bomb plot – ie, the sort of people who might disapprove of cartoons of the Prophet – and to see him shrugged off.

Neither is the film entirely one-sided. There are some pay-offs, of course, violent ones, and we feel good about that. But we’re supposed to. It’s a trick. And this is where I part company, I suspect, with the agenda of the film-makers.

The film’s message is that violence begets violence and is therefore bad. But the message I took away – or, perhaps more honestly, the idea the film was unable to take from me – was that he who develops the most violent retaliatory deterrent is likely, also, to have the fewest active enemies. (To wit: Christian beats the school bully half to death, the bully stops bullying, the bully wants to be Christian’s friend. Job done.)

Watch the trailer to In a Better World

To play out the moral alternative – to demonstrate, contrary to this childish discourse, who is the "bigger man" – Anton, the redeemer of worlds, in the most painful scene of the film, allows himself to be slapped around by a vulgar racist car mechanic. In front of his sons. This is a serious affront to some even more seriously hardwired criteria for manliness, and Anton’s rationale – "If I hit him then I’m a jerk, too" – doesn’t wash, least of all with his kids.

Perhaps not needless to say, all the violence in this film (the doing of the violence, anyway) involves men. And I couldn’t help feeling that, when it comes to violent action, men, as a whole, are damned if we do and damned if we don’t. The male impulse is to fight, to protect, and to make the world right through strength. Old school, certainly. But the men in this film who don’t fight, who do not display strength, who give up, are judged for that, too.

Ultimately, In a Better World says of violence what Bamboozled said of racism: namely, we’re all getting it wrong. And the film delivers its argument well – I just didn’t quite buy it.

- In a Better World is released on Friday

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Comments

...