Children of the Revolution | reviews, news & interviews

Children of the Revolution

Children of the Revolution

Remarkable documentary about Fusako Shigenobu and Ulrike Meinhof

As well as recounting the stories of two of the women who would become figureheads for the revolutionary movements that grew out of the social unrest of 1968 - Germany’s Ulrike Meinhof and Japan’s Fusako Shigenobu - Shane O’Sullivan’s documentary Children of the Revolution intriguingly juggles the political and the personal.

Children may open with dramatic newsreel of exploding airplanes, and its assembly of news archive from some of the more violent terrorist incidents of a decade is more than compelling, but its still centre captures something different - the reminiscences of those who were part of the events, and most notably the stories and reactions of daughters Bettina Meinhof and May Shigenobu.

O’Sullivan doesn’t need to emphasise the differences between the destinies of his two subjects – UK viewers are likely more familiar with Germany’s Baader-Meinhof Group than Japan’s Red Army – because both the facts and reactions of contemporaries point them out so starkly. Nowhere more so than the ways in which they are remembered by their daughters.

Meinhof’s (pictured left) commitment to motherhood, once she was already on the German wanted lists, was to have her two daughters kidnapped to Italy from where they were due to be moved to Jordan to train as revolutionaries. Snatched back by a friend, they returned to familiar German semi-bourgeois life in Hamburg. Later meetings with their mother, once she was back in prison in Germany, were few, and it seems cool. Bettina talks of her mother’s instinct to “play God Almighty”, and of her relief when she was able to “pick up her small life again” back home. Reactions from Meinhof’s more conventional German early friends and contemporaries display a similar incomprehension: her mutation from successful left-wing journalist to terrorist is ascribed to the results of a brain operation, or compared to the change of a personality due to heroin addiction. One detail says the heartbreaking whole: Meinhof hung herself in prison in 1976 on Mother’s Day.

Meinhof’s (pictured left) commitment to motherhood, once she was already on the German wanted lists, was to have her two daughters kidnapped to Italy from where they were due to be moved to Jordan to train as revolutionaries. Snatched back by a friend, they returned to familiar German semi-bourgeois life in Hamburg. Later meetings with their mother, once she was back in prison in Germany, were few, and it seems cool. Bettina talks of her mother’s instinct to “play God Almighty”, and of her relief when she was able to “pick up her small life again” back home. Reactions from Meinhof’s more conventional German early friends and contemporaries display a similar incomprehension: her mutation from successful left-wing journalist to terrorist is ascribed to the results of a brain operation, or compared to the change of a personality due to heroin addiction. One detail says the heartbreaking whole: Meinhof hung herself in prison in 1976 on Mother’s Day.

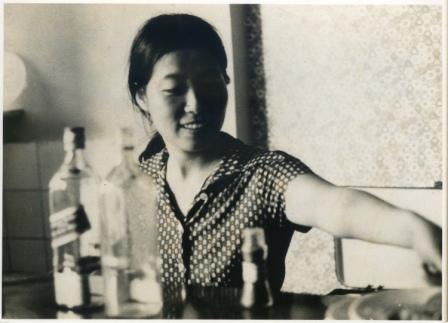

Shigenobu (pictured below right) comes across completely differently. Propelled into radical politics after the 1968 student uprisings in Tokyo, she consciously went to support the Palestinian cause in 1971 – Meinhof seemed almost to have ended up in the Middle East by accident – and worked for it full-time, in considerable danger, and with the real conviction of an internationalist.

It was clearly a lonely time, and only a pregnancy after a relationship with a fellow Arab freedom fighter brought her a clearly deeply loved daughter, May (who wouldn’t know who her father was until she was 16, for safety reasons). Perpetually having to escape potential assassination meant that May saw little of her mother, yet there is no sense of accusation when, now in her late thirties, she estimates that she has had a cumulative total of roughly five or six years contact in all.

It was clearly a lonely time, and only a pregnancy after a relationship with a fellow Arab freedom fighter brought her a clearly deeply loved daughter, May (who wouldn’t know who her father was until she was 16, for safety reasons). Perpetually having to escape potential assassination meant that May saw little of her mother, yet there is no sense of accusation when, now in her late thirties, she estimates that she has had a cumulative total of roughly five or six years contact in all.

May (pictured below left) has also been lucky to have put down genuine roots in the Middle East, especially Beirut, and we see her there in reflective, but clearly tranquil moments. Now a television journalist in Japan, she puts forward a balanced defence of, and argument for, her mother, and for the beliefs that saw Shigenobu devote her life to a foreign cause (though the Japanese Red Army was highly active fom the 1970s onwards in hijackings and embassy seizures, apparently no one was killed in their activities).

If you suspect that for Meinhof’s children their past and attitudes to their mother have been shut away, and likely remediated by intensive therapy, May’s attitude to her mother is wonderfully open. Fusako was arrested in 2000 on a secret return visit to Japan, and we see archive footage of her being escorted away by police emanating a very powerful sense of serenity; May, until then a completely stateless person, returned home, and now visits her every week in the prison in which she is serving a 20-year sentence. If Germany rejected Meinhof as an aberration, Japan appears to see Shigenobu as a national embarrassment – though the popular image of her there as a “Red Queen of Terror” could hardly seem more at odds with the individual we come to know from archive footage (though O’Sullivan met her in prison, filming there was prohibited).

It also leaves the impression that there’s rather more wisdom to be found in Japan than Germany – and little is more incisive in the film than May’s reflection that the events of 9/11 destroyed the very idea of the cause of the freedom fighter, as well as chances of understanding Islam, and the Arabic and Middle Eastern cultures. May has a presence that comes to dominate the second half of the film, in a quiet, increasingly moving way.

It also leaves the impression that there’s rather more wisdom to be found in Japan than Germany – and little is more incisive in the film than May’s reflection that the events of 9/11 destroyed the very idea of the cause of the freedom fighter, as well as chances of understanding Islam, and the Arabic and Middle Eastern cultures. May has a presence that comes to dominate the second half of the film, in a quiet, increasingly moving way.

Japan also seems a culture closer to O’Sullivan than Germany: the extra feature on this DVD is his earlier film from 2002, Under the Skin, which examines those same 1968 student rebellions there through interviews with the cultural figures who were involved in them (the film-maker Masao Adachi is a strong presence both here and in Children). Effectively, Under the Skin asks the questions – what was Japan then, what has it become now?

But I don’t think that, as in Children, O’Sullivan sets out to answer them. That is the achievement of this remarkable documentary – extremely well put together, it weaves a fabric from the details of history and the distinctive stories of those interviewed. A rich web, indeed.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Add comment