Filming Woodstock: Fact, Fiction, Fantasy | reviews, news & interviews

Filming Woodstock: Fact, Fiction, Fantasy

Filming Woodstock: Fact, Fiction, Fantasy

Aquarius revisited: turn on, tune in, cop out ?

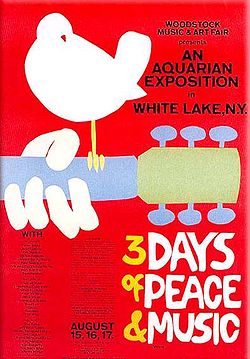

The most famous rock festival in history celebrated its 40th anniversary this summer in an orgy of nostalgia.

James Schamus, the writer and producer of Taking Woodstock, concedes that the anniversary was a mixed blessing for his movie. "The media blitz was just insane. Everywhere on television there was a special about it, from CNN to The History Channel. I think people probably felt it was a little too commoditised. A little too bumper-stickery. There was an exhaustion, and we did sense that a bit, I must admit. But at the end of the day you can't really second-guess what we coulda shoulda done." If such distinguished film-makers feel so strongly moved to make movies about Woodstock, it must be because - to paraphrase the cliché - they couldn't have been there. Kopple, now 63, was, as she recalled to salon.com, "studying and working. I was not at Woodstock, but I feel like I was." She since seems to have developed a minor obsession with the subject and has already made two documentaries, Woodstock '94 and My Generation, which cover the concerts marking the festival's 25th and 30th anniversaries.

If such distinguished film-makers feel so strongly moved to make movies about Woodstock, it must be because - to paraphrase the cliché - they couldn't have been there. Kopple, now 63, was, as she recalled to salon.com, "studying and working. I was not at Woodstock, but I feel like I was." She since seems to have developed a minor obsession with the subject and has already made two documentaries, Woodstock '94 and My Generation, which cover the concerts marking the festival's 25th and 30th anniversaries.

Lee, 55, was growing up far away in his native Taiwan while Schamus, 50, was grounded at home in Los Angeles. "My mother had locked me up because, the week before, some hippies showed up in our neighbourhood and killed Sharon Tate," recalls Schamus (below left). "We didn't know then that it was the Manson family, but we certainly knew that there was this kind of countercultural thing that wasn't too good. My mother was convinced, of course, that I was next. So we watched these incredible scenes on our black and white television of the New York State thruway being closed down." Half a million people converged upon the small faming town of Bethel where the festivities took place. But, despite widespread fears, it was truly a weekend of peace and love. "At this moment of innocence, there was not a single incident of reported violence. So it really was a bit of a Utopia. Yet, from where I was sitting, it looked like we were under siege. So there were all these contradictions."

Half a million people converged upon the small faming town of Bethel where the festivities took place. But, despite widespread fears, it was truly a weekend of peace and love. "At this moment of innocence, there was not a single incident of reported violence. So it really was a bit of a Utopia. Yet, from where I was sitting, it looked like we were under siege. So there were all these contradictions."

Taking Woodstock views the event through the eyes of the real-life figure of Elliot Tiber (played in the film by Demetri Martin, pictured, below centre), a young man whose hardscrabble Russian immigrant parents owned a motel in Bethel. Tiber became a key player in setting up the festival and, in the process, was able to come to terms with his own identity as a closeted gay man.  "The film is a very small, intimate family drama-comedy in which this very dysfunctional Jewish family ends up sorting itself out," says Schamus, defending his decision to show virtually nothing of the big event. "Commercially speaking, putting Woodstock in the title has been a bit of a headwind for us because people think it's going to be a concert movie. But there's already a Woodstock concert movie! The whole joke of our film is that our hero never gets down the road.

"The film is a very small, intimate family drama-comedy in which this very dysfunctional Jewish family ends up sorting itself out," says Schamus, defending his decision to show virtually nothing of the big event. "Commercially speaking, putting Woodstock in the title has been a bit of a headwind for us because people think it's going to be a concert movie. But there's already a Woodstock concert movie! The whole joke of our film is that our hero never gets down the road.

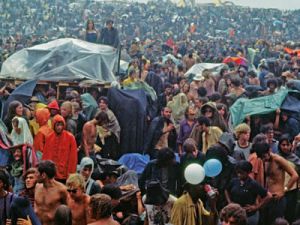

"It's a very American idea that you can have the Woodstock experience and be right up there viscerally on stage with Joan Baez and Joe Cocker, but that was a fantasy created by the makers of Woodstock. It was not the reality for people who were there. The vast majority were having sex or skinny-dipping in the lake or dropping acid or hanging out with their friends.

"It was not like the way concerts are done now: they didn't have JumboTrons, those gigantic screens all round the arena, and they didn't have that tight organisation and logistics. It was a mess. You couldn't really get that close to the stage after the first day. For most people, Janis Joplin was a flea, a speck of dust on the horizon. And the sound would have been a low-throbbing hum of bassline. Music infuses every moment of our film, but it's in the background, part of the ambient environment." Woodstock Now & Then takes a very different tack. In a bid to investigate the gap between "Woodstock the event and Woodstock the myth", Kopple (left) explores the larger picture, talking to people who attended the festival, including Bobbi and Nick Ercoline, the couple wrapped in the pink blanket on the cover of the Woodstock soundtrack, and the individuals involved in the 1970 documentary, extensive footage of which is incorporated into her own film. Wadleigh and Thelma Schoonmaker, Woodstock's editor, are interviewed, as well as Michael Lang, the flamboyant hippie-impresario who was instrumental in getting the whole thing off the ground (Lang, pictured below right, still looking impossibly young with his trademark mop of wild curls, also produced Woodstock Now & Then).

Woodstock Now & Then takes a very different tack. In a bid to investigate the gap between "Woodstock the event and Woodstock the myth", Kopple (left) explores the larger picture, talking to people who attended the festival, including Bobbi and Nick Ercoline, the couple wrapped in the pink blanket on the cover of the Woodstock soundtrack, and the individuals involved in the 1970 documentary, extensive footage of which is incorporated into her own film. Wadleigh and Thelma Schoonmaker, Woodstock's editor, are interviewed, as well as Michael Lang, the flamboyant hippie-impresario who was instrumental in getting the whole thing off the ground (Lang, pictured below right, still looking impossibly young with his trademark mop of wild curls, also produced Woodstock Now & Then). Kopple looks at the issues of providing security and food for such a huge gathering and the financial chaos left in its wake: the producers of Woodstock had to relinquish the rights to the film in order to cope with a million-dollar deficit and an enormous flurry of lawsuits. The bad blood persists today, as Schamus discovered when setting up his own movie.

Kopple looks at the issues of providing security and food for such a huge gathering and the financial chaos left in its wake: the producers of Woodstock had to relinquish the rights to the film in order to cope with a million-dollar deficit and an enormous flurry of lawsuits. The bad blood persists today, as Schamus discovered when setting up his own movie.

"Bethel has a museum dedicated to Woodstock and the site was bought by a wealthy businessman and turned into a very upscale venue. But the people originally involved in the festival have not co-operated in that. Meanwhile, down the road, they have tried to recreate more of the Sixties sense of the free concerts, but the town has never allowed them the permits. So there have been lots of stresses. The legacy of Woodstock is very contested and after a few minutes I realised it was going to be impossible to shoot there." (Taking Woodstock was filmed in the nearby town of New Lebanon).

Some critics accuse Lee and Schamus of offering a thickly rose-tinted vision, of "completely endorsing the sanctified view of Woodstock as the one, brief, shining moment of the Age of Aquarius," in the words of the review in Variety. "They are right, but right in a very, I find, limited way," Schamus says. "I think we should have a rose-tinted view of some things.

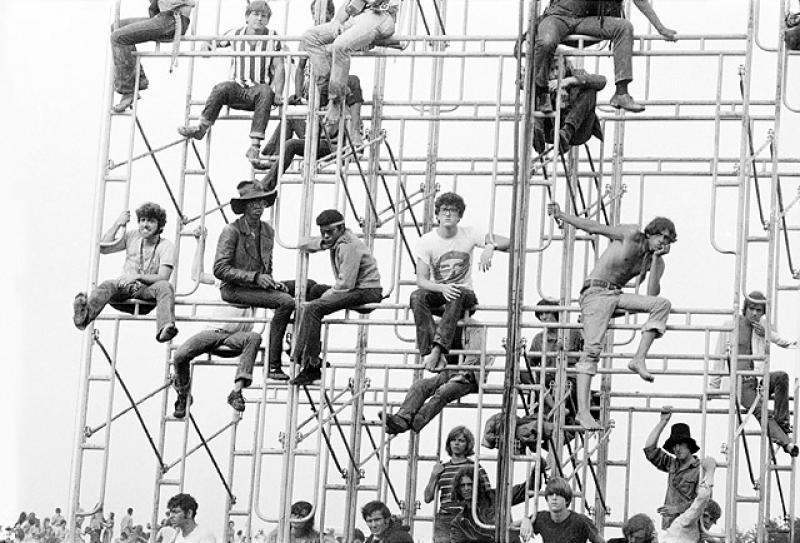

"You don't put half a million people together [some of them are caught in this archive image, right] and walk out without a single incident of violence without acknowledging a kind of a miracle. If you don't do that you're just being cynical. Part of the ethos of Taking Woodstock is to go back and reclaim the dynamic and hope and optimism of that generation because some of it has been lost and abused.

"You don't put half a million people together [some of them are caught in this archive image, right] and walk out without a single incident of violence without acknowledging a kind of a miracle. If you don't do that you're just being cynical. Part of the ethos of Taking Woodstock is to go back and reclaim the dynamic and hope and optimism of that generation because some of it has been lost and abused.

"I always say to Ang that he ought to take his name off this movie. People are going to see it and feel cheated because at the end they don't feel suicidally depressed by some meaningful tragic experience. People make comedies, but they don't make movies about being happy these days."

Among Lee's many darker films is his adaptation of Rick Moody's novelThe Ice Storm, for which Schamus also wrote the screenplay. Set in the early Seventies, it offered a decidedly frosty take on the way the opportunities grasped in the Sixties quickly turned sour. "People ended up with the drugs and the sex but they didn't have the actual transformative experience. It was almost an injunction to enjoy a freedom that, by that point, was illusory."

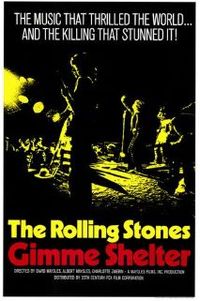

Woodstock has left a mixed legacy. Less than four months later, on 6 December 1969, another festival was held in Altamont, Northern California. The result, documented by the Maysles Brothers in the film Gimme Shelter, was wide-spread violence, including a homicide. "Everyone says that Woodstock was the height of the Sixties and Altamont was the end of the Sixties," Schamus notes. "But it was the same team that put on those two concerts."

Woodstock has left a mixed legacy. Less than four months later, on 6 December 1969, another festival was held in Altamont, Northern California. The result, documented by the Maysles Brothers in the film Gimme Shelter, was wide-spread violence, including a homicide. "Everyone says that Woodstock was the height of the Sixties and Altamont was the end of the Sixties," Schamus notes. "But it was the same team that put on those two concerts."

Yet the wheel has spun again and some feel we are on the point of a new Age of Aquarius. Near the end of Woodstock Now & Then, several people, including Gail Collins, a columnist for The New York Times, compare the rock festival to the inauguration of President Obama."Woodstock is still relevant today because people really care about what's happening in our world," Kopple told salon.com. "I think once again we have that feeling of hope, that things are going to be OK."

Schamus for his part is more circumspect. "Obama does represent hope, change, ‘Yes we can,' etc., etc. But, look, the fundamentals are that corporate America has still managed to save itself while making sure that no-one else is even getting the crumbs off the table.

"Certainly this is a kinder, slightly more gentle administration. But we have yet to go back and feel the power of the Sixties. Not that, through some kind of nostalgic recreation, we're going to find our way out of our current morass. We have to create our own solutions. In Taking Woodstock, we wanted to go back to the point when that door opened to all this stuff and say, 'There was something valuable there'."

www.history.com/content/woodstock

www.takingwoodstockthemovie.co.uk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Add comment