theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Karl Wallinger | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Karl Wallinger

theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Karl Wallinger

RIP Karl Wallinger: a 2012 interview with the World Party wizard on aneurysms, Robbie Williams, drugs and fame

In February 2001 a brain aneurysm nearly killed Karl Wallinger. It didn’t do World Party many favours either. The aftermath of devastating illness resulted in a five year hiatus for his band, followed by a gradual, tentative return. Since 2006 there have been shows in Australia and America, but no new music and no gigs on this side of the pond. Until now.

Wallinger has returned to the fray with a five disc collection called Arkeology. Spanning 1984 to 2011, it contains a couple of new songs but is largely comprised of postcards from the past, written but never sent. There are demos, B-sides, lost songs, live tracks. It’s necessarily patchy but a lot of fun, and testament to Wallinger’s torrential talent as a songwriter and record maker. Its release will be followed by the first World Party shows in Britain for 15 years, including a date at the Royal Albert Hall.

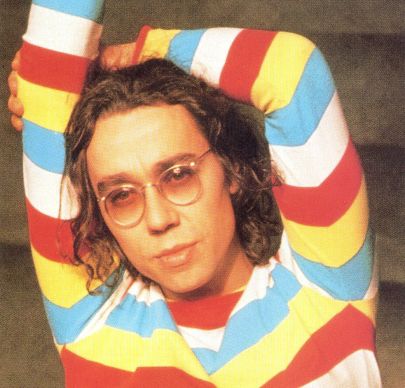

A “song creature all my life”, Wallinger was born in Prestatyn in 1957. He attended one of Britain's top private schools – Keith Allen’s nickname for him back in the powder-fuelled Nineties was simply “Charterhouse” – before coming to London in the late 1970s. At first he plied his trade as keyboardist for hire: he became musical director of The Rocky Horror Show at the age of 20. Later, in the mid Eighties, he joined The Waterboys, playing on A Pagan Place and This is the Sea.

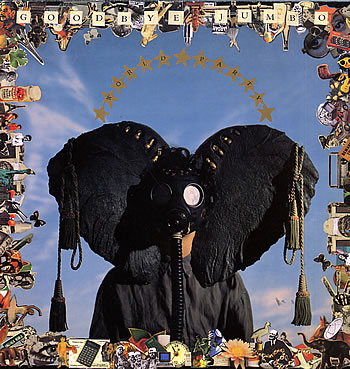

He left in 1986 to form World Party, essentially a solo vehicle for Wallinger’s attempts to distill the essence of every classic rock and pop act - Dylan, Prince, the Rolling Stones, Sly Stone, the Beach Boys, perhaps above all the Beatles - into one bubbling, funny, funky, heartfelt and wilfully chaotic brew. In the early days Wallinger’s band mates included Guy Chambers (pictured with Wallinger, second right and far right respectively), who went on to become Robbie Williams’ producer and co-writer. For a while Wallinger seemed poised to achieve a similar level of mainstream success. The first World Party single, “Ship of Fools”, was a Top 30 hit in America. His second album, Goodbye Jumbo – containing the single “Put the Message in the Box” - was lavishly praised and won Q magazine's Album of the Year award in 1990.

He left in 1986 to form World Party, essentially a solo vehicle for Wallinger’s attempts to distill the essence of every classic rock and pop act - Dylan, Prince, the Rolling Stones, Sly Stone, the Beach Boys, perhaps above all the Beatles - into one bubbling, funny, funky, heartfelt and wilfully chaotic brew. In the early days Wallinger’s band mates included Guy Chambers (pictured with Wallinger, second right and far right respectively), who went on to become Robbie Williams’ producer and co-writer. For a while Wallinger seemed poised to achieve a similar level of mainstream success. The first World Party single, “Ship of Fools”, was a Top 30 hit in America. His second album, Goodbye Jumbo – containing the single “Put the Message in the Box” - was lavishly praised and won Q magazine's Album of the Year award in 1990.

Gradually, however, the promise petered out, although one of his songs, “She’s the One”, became a huge hit in 1999 for Robbie Williams. Nowadays, the credo is simple. "Everybody wants a fridge, a fast car, a beautiful woman... and possibly some drugs,” he says. “But I just know I’m here and want to play some music and make good use of my time. It’s that cheesy.”

Demolishing shepherd’s pie in the Groucho Club in Soho, Wallinger seems in decent shape: older, rounder, weathered, but not entirely dissatisfied with his lot. World Party’s music was filled with ecological doomsaying long before it became a fashionable cause, and he has retained the aura of a militant, comic-misanthropic stoner philosopher. Dressed down in sky blue T-shirt and jeans, he is opinionated, sharp, funny, wry and at times a bit cross. Good company, in other words. He has a wicked grin and is an excellent mimic, slipping easily from Outraged of Tunbridge Wells to comedy Northerner. There is evidence of both a kind heart and a sharp tongue; you suspect the latter has got him into a few scrapes in the past. Lest anyone should think this pop classicist has lately become a devotee of grime or black metal, his dog is called Ringo and his ring tone is “Family Affair”.

"Put the Message in the Box" video

GRAEME THOMSON: It must have been pretty daunting trawling through nearly 30 years’ worth of old music?

KARL WALLINGER: My label manager compiled four of the CDs. I couldn’t do it myself, it was making me go very sleepy – it was too much. It was crazy, there was about five and half days of music on a hard drive. Some things astonished me, like “Words”. It was just something I did one day and put in a box, but I liked the banal Americanised vocal. There are always things that aren’t part of an album process and just pop along. The strange time when things get lost is when you’ve finished an album and you’re going on tour in two months. The bits that get done in that little gap tend not to be part of anything. There are songs that got lost in the mix, so this is about just getting them out there.

Do you feel you’re still feeling your way back into being creative after your aneurysm?

Not really, no. It has been a relearning process, and I’m a different person, I think, than I was – probably better. A change is as good as a rest! It’s just been a question of getting back into making music because you want to.

I remember a Bob Dylan quote after he had his motorcycle crash in 1966, and it was something along the lines of having to learn to do consciously what he used to do instinctively. Does that resonate with you?

It makes you think more about it. The only thing that affected me from a practical point of view was losing my right hand vision. I used to look at the shapes on my right hand when I was playing piano – that was the language I used to communicate with the music. I can’t see that now. I'm left handed, so I can’t see the end of the guitar. I was playing a few jazz guitar chords for a while! If I look at you I can’t see the left hand side of your face, you’re looking around a corner at me. It’s strange. It’s not something I’ll ever really get used to. The main thing is Christmas shopping. It’s amazing how much we’re aware of our peripheral vision, so when you’re Christmas shopping and you’re heading towards somebody they think that you’ve seen them. So there’s a lot of collisions going on – they don’t come up on the radar. So I say, “sorry”, because of course if you’re the spazzy one you always have to apologise to the perfect human specimen... In the end I probably play better than I did because I was practising so much.

I can’t get my head around the stupidity of materialism. Still. Call me an old hippie

You said you thought you had become a better person. In what sense?

It’s sort of uncommunicatable. I have no problem talking about it, it’s just hard to put into words. You become more philosophical about the nature of existence. What makes you happy can be really simplified, because just being around is pretty good after that kind of thing. It tempers your desperate desires, they become irrelevant, whatever they are. It makes you more down to earth in a way, which is good, although I never felt like I wanted to rule the world. It shows you that you are driving a vehicle, whereas before you’re not conscious of driving the vehicle: you are just being you, moving along. When something like that happens you have a consciousness of being you moving along that you didn’t have before. It’s a difficult thing to explain – you can see yourself doing those things for the first time. It’s not necessarily that helpful, but it does temper your actions. I don’t give a shit even more than I ever did, but I was already going like that anyway. The only time I have ever done any good things is when I’ve been out of control, in the sense of not being conscious of working, but just doing. That’s the place that you have to get to. The best way of making music is by being unaware of real world parameters and going to the place where the muse is, where the music is, and not thinking about practical things. There are ways that people find of achieving that particular brain environment – and, um, I still do!

Do you?

Mmmm. Not heavily, just mildly, in the way that several million people do but for some reason we’re not supposed to be allowed to. Sitting around listening to music or eating or having sex is deemed to be very, very dangerous as far as the government is concerned. It’s crazy, just insane. And they’re also missing all the tax they could put on it and make money for their wicked lives.

Releasing the first World Party album in 12 years and playing your first UK shows in even longer, do you worry about where you fit in?

Of course. It’s weird, I’ve been the guy who takes my dog for a walk on Hampstead Heath for 12 years. I’m an album artist. The fact that it has boiled down to one track going to iTunes is greatly distressing to me. There’s an art form there that used to be delineated by how much music you could get on to a vinyl album. Then I missed the relationship between side one and two when it went to CD, and it didn’t sound as good. Now that we’ve gone online it’s just a track thing and that’s a bit boring, really, especially when you hear most of the tracks. It’s all very disposable. The richness of it has been dissolved. There and hundreds of thousands of people making music, which is great in a lot of ways, but [he adopts stern old buffer voice] I think they should have to pass a test, and if they don’t they should be unable to obtain musical instruments and stop making such a fucking racket. Not really, but there’s a little bit of that in me. Music has been invaded. There you go. It has been invaded by machines. Copy and paste has won the day. If you’re having a lot of success in the charts maybe you’ll think it’s better. If you’re confused about it and haven’t produced anything for a long time you’ll think it’s worse. I dunno, maybe I’m just too old, but I used to think music had something to do with commenting on what’s going on. It’s the final victory of the corporate world. It has infected everything, it’s trans-border and there is no way to control it. As a culture it has meant: fuck everything and set the bottom line.

Many people would argue that pop music has always essentially been a disposable adjunct of the entertainment industry, and the late Sixties and Seventies were just a blip...

Many people would argue that pop music has always essentially been a disposable adjunct of the entertainment industry, and the late Sixties and Seventies were just a blip...

I think it’s beyond that. In the past the modus operandi and structure of the business were such that certain things happened that don’t happen now. There are more groups of people with general business qualifications now. In the past it was pioneering individuals, and the format of the LP was on an upward spiral and making progress. It ran into a time barrier, and that was digital technology. Everything has changed. Democratisation has come in – does that make it any better? I don’t give a fuck about Facebook, I don’t give a fuck about Twitter. I don’t think it’s an age thing, I’ve got friends who are on it all the time. But I get my rocks off in other ways. We can all talk to each other and arrange protests and stuff, but there’s so much of it that it almost doesn’t matter. It’s a difficult time to nail down, but that’s OK.

Do you find that sense of flux inspiring as a writer?

I don’t find it too inspiring, no. I don’t find it very inspiring being stuck with a bunch of people creaming the money out of everyone and leaving the majority of people in the trough. The middle class are disappearing? Boo hoo. How do you make the upper class disappear, that’s the question, and leave all their resources to everybody else? I’d rather live in a world that is much more mutually owned – the idea of the word communism with a small “c” is very attractive, but we know the trouble with that: it’s the politburo or any oligarchic power structure - you’re always devilled by that. It’s very difficult to see how it works. I just think we should ask rich people if they would mind being a little less rich. Come and join in! Like, there should be a division of the Batman squad that turns up at auctions. If someone is about to pay £100 million for a painting they should intercede just as the money is changing hands: take the £100 million, take the painting and put it in a gallery, and say, Phew that was a close one! You nearly spent £100 million on a fucking painting when we still have loads of people to feed and things to do. I can’t get my head around the stupidity of materialism. Still. Call me an old hippie.

When did you first realise you could make a living through music?

I never really thought that. I just had to do it, I didn’t think about earning money, I didn’t know how to exploit my talents, I just knew I had to come to London. Before that, I heard music on the radio and saw my sisters pushing the sofas back and dancing round the room to the Beatles, or Buddy Holly or Junior Walker or whatever it was. I thought, That looks like good fun. I’ve always had a good ear for sound and it’s always been like that. I didn’t want to do anything else. I didn’t question it. I was always making up tunes.

What kind of music was in the house?

We had a funny record collection at home. There were big moments in strange records. George Martin’s “Theme One”, from his Beatles orchestrations... I just thought that was tremendous for a short while, all that distorted Hammond. Hank Levine’s “Image Part Two”, which my brother always used to say was the soundtrack to driving over the Golden Gate Bridge with your arm over the double seat. And it really is. Futuristic Fifties stuff. That really affected my musical library. You fill it up with memory cards that you can plug into the mainframe so you can draw from any bit of it.

I used to think we were all right, now I think we’re a bunch of twats

And The Beatles loomed large, presumably?

Yes, there’s a lot of stuff in my music that’s Beatleesque, but I don’t do pastiche. When I do pastiche, you know all about it! I’ve never dressed up like that. I didn’t have a bouffant hairdo, I didn’t have funny side-breezers. In the beginning I wore the embroidered Sergeant Pepper-y jacket for one video. I get hammered with this retro thing, but I’m not retro. I’m writing songs about now – in fact, the songs I wrote back then are even more relevant now than they were when I fucking wrote them. I wasn’t trying to be ahead of the curve, I was just writing about things that seemed obvious to me at the time, and we still haven’t done anything about it because we’re a bunch of twats. That’s probably one of the main things that has changed in my head: I used to think we were all right, now I think we’re a bunch of twats. Me too. I can be as much of a twat as the next guy.

Did you study music at school?

Yes, I was a music scholar, I played oboe, which was one of the reasons I had the aneurysm, I think. Lots of wind players have aneurysms because of the high pressure blowing. I probably weakened some vein. After that I came to London wanting to do music. I got a job at ATV music, who ran Northern Songs before it was sold. I read a lot of publishing contracts. When I moved up to the accounts department I used to write “pay John Lennon £160,000”, get it signed and send it to him. I got a writing deal there because I used to play piano at lunchtime. I got invited to the writer’s meetings but I didn’t know what anybody was talking about. I thought everyone would be talking about music: “Shall we talk about Beethoven or the Brotherhood of Man?” But it wasn’t what I thought it was going to be... it was a whole load of people writing songs for cheesy pop acts.

Did you do a bit of that?

Did you do a bit of that?

Not really, no. I joined a funny collection of guys who were the backing band to Peter Straker, who was quite a character. For a while I played keyboards for him - getting my hair done in Kensington and playing TV shows in Holland where some 23-foot long loaves were the next act. After that I went on a four or five year lost weekend and made a racket in bedrooms in King Cross. We had notes put through our door by a rather nice, patient neighbour: “To the drummers of Wilmington Square...” I played some gigs, had some funny bands called things like Invisible Body Club, who used to rehearse in a dug out hole in the ground. I kept listening to stuff – Joy Division, Comsat Angels – and trying to write. It was a growing time, with all the world’s tobacco to smoke. The only thing that amounted to anything during that time was being musical director of The Rocky Horror Show, which was great. I was 20, and the guys in the band were died-in-the-wool men about town, and they were all, mutter, mutter, mutter. But as soon as we hung out it was cool. I did love that show. I still sit down and play “I’m Leaving Home” and “Sweet Transvestite”, it’s got some great numbers in it. A guy called Tony Hicks played the drums. He lived in Brighton and sometimes he would try to shave four minutes off the show by playing everything at a frantic pace. Or he would bring a TV in when Middlesbrough were playing football and when they scored he’d do a big drum roll. Which wasn’t very often, obviously. It was very funny. Tracey Ullman and Gary Olsen were in it and I did it for a year, 1977-78, at the Comedy Theatre.

In 1983 you joined The Waterboys. I noticed that the long lists of credits on Arkeology to “all the musicians it’s been my pleasure to work” manages to omit Mike Scott...

Mmm, funny that innit.

What’s the problem?

Just some ongoing bitterness. I’m not thinking about it too much, it’s not keeping me awake. Whatever, man, it’s all about ego and life and the universe and everything. We live and learn. Water under the bridge. Good luck to him, may he tour and release albums as long as he wants. I haven’t got a problem with it, really. [Comedy voice] I’m completely cured now! We’re too long in the tooth to be bothered with all that.

Why did you leave?

I just wanted to do some things and if they weren’t going to be needed there I should go and do them somewhere else, because it was just going to lead to problems. I stayed for a year after I got the solo deal and then thought, Fuck this, I’m out of here. Make your own sausages! I had a clear-ish musical vision. I wasn’t completely formed, but I thought there were better ways of doing things so I decided to go and find out.

What do you remember about making the first World Party album, Private Revolution?

I went to an estate agent in Woburn and said, “Do you rent out places in the middle of nowhere? I want somewhere without any neighbours.” They said, “No, but go and see Ed at the Old Rectory.” He was a painter, and the estate put him into empty places just to look after them. He was in this amazing Old Rectory with eight bedrooms and this amazing 500-year-old Lebanese cedar tree in the garden and stable blocks. He had a 30ft long room as his studio and the rest of the house was empty. It was amazing – there were 12 doves who lived in the roof who I thought were the spirit of the nuns who used to live there. It was a very mystical place for me, and I just went to work in my little first floor room and then went walking in the fields after a night of playing music. It was fantastic, apart from the first time I went, when I didn’t know there was a safari park nearby. At 6.30 in the morning I was going through this sunny field and there was this ROOOOOOAAAR!, and I was, Oh my God, what the fuck is that? I went running back and Ed got up and said, “It’s the safari park!” So that was OK, except when the hippos ended up in the local swimming pool.... It was just a great place to be, and that album will always be special because it was the first time I thought, Wow, I’m making a record. All by myself, pretty much, but to me it was like being in Abbey Road! And I got a Top 30 in the US singles charts with “Ship of Fools” – never done it since! It was just one of those songs. I thought, I know I’m not mad. It was well received enough to get me on to the next thing. I stayed there to do some of the tracking on Goodbye Jumbo and then moved to London where I am now.

Watch the video for "Ship of Fools"

Where do you work now?

I have the biggest home recording studio in the world. Except it’s not in my home, it’s a big warehouse place in North London – my view is pretty great. I look straight down at the Shard, I’ve got the City there, Canary Wharf over there, the GPO tower. It used to be a fire watch in the war. I’ve had it for years and I’ve been able to do what I want to do for a long time. I’ve always had my own place, so everyone is just catching up really.

Around the time of Goodbye Jumbo World Party seemed poised for what used to be called The Big Time. Do you have any regrets about how it panned out?

I never think there’s any point. There are good points and bad points in any situation. I just reacted to what was going on. I suppose the main point of stupidity was when we did Jumbo and won the Q award with it, then we disappeared for three years. You never do that. That was all to do with an argument between the manager and the record company – and the record company wanted to show how they won. They were full of shit. We were meant to be supporting Neil Young in America, and we were taken off the tour and that was it. Go away. Wow. There was a moment there, door opens, door closes. But from what I’ve seen of what success means to a lot of people I’m kind of glad I wasn’t massively successful when I was younger. I was already 31, married with two kids. It’s strange the idea of any of that mattering after having your head sawn off.

I never think there’s any point. There are good points and bad points in any situation. I just reacted to what was going on. I suppose the main point of stupidity was when we did Jumbo and won the Q award with it, then we disappeared for three years. You never do that. That was all to do with an argument between the manager and the record company – and the record company wanted to show how they won. They were full of shit. We were meant to be supporting Neil Young in America, and we were taken off the tour and that was it. Go away. Wow. There was a moment there, door opens, door closes. But from what I’ve seen of what success means to a lot of people I’m kind of glad I wasn’t massively successful when I was younger. I was already 31, married with two kids. It’s strange the idea of any of that mattering after having your head sawn off.

By the time of Egyptology in 1997 the momentum seemed to have gone...

I split with record company and then my manager. It was basically inter-business bullshit, and that album got lost in the business side of things. It didn’t pan out. It was politics behind the scenes, really. I’ve got a hand in it as well. I didn’t want to make a video for “She’s the One”, which should have been a hit for me. The good thing about it was that it led to me owning all my music, which is great. I couldn’t have contemplated leaving the music with EMI, because it was all done in my own place. Music is what you want, and it enabled me to be way ahead of the game as far as exploiting my own music online and earning money with films. I earned far more money away from the record company than I ever did with them.

Did you do all right?

I didn’t do all right with records. I did all right with publishing. We always made crazy expensive videos and had huge amounts of tour support. Which was kind of stupid. We live in reality now, which is a lot better. But Robbie doing “She’s The One” saved my arse financially because I wasn’t doing anything at all. After the aneurysm I was holding on to the handrail for a bit thinking, What happened?

Is it true that you had no idea that Robbie Williams was recording “She’s the One”?

It was very strange. Nobody phoned me. Guy [Chambers] came by the studio when I was doing Egyptology and while he was there I played him “She’s the One”... he even used the band that I’d just come off the road with, because they knew the track. They all came in recorded it with Guy. It’s pretty much identical, just Robbie gets the words wrong – ‘cos he can’t read. He sings “fine” instead of “fun”. That did annoy me, that he hadn’t sung the right words. But it’s a double thing: on the one hand you lose your friends, on the other you make a lot of money. And it was great that the song got recognition. Songs are like naughty kids, strange bits of you that pop off and go and have their own lives – and they’re having all the fun. “She’s the One” is at the Brits and I’m at home having a cracker dipped in water. Whatever. It was fucking lucky that it was a hit. I’d have had to sell the dog otherwise. That was probably the most important piece of success.

Everyone seems to think that it’s about your mum....

No, it was for a film. I was told: She’s the one. Boy meets girl in New York. I thought about lovers in New York and it just came. Bang. I recorded it in about an hour. It’s a simple thing, a night with a little bit of inspiration. Simple is good. Simple is great.

Watch “She’s The One” live on Later... with Jools Holland

World Party has always basically been you. Are you a control freak?

Not any more. I probably was. That’s another thing that has probably gone – just the futility of it.

But is being alone, holed up in the studio, still your preferred way of working?

I love the first McCartney solo album, and Innervisions by Stevie Wonder, which is pretty much him on his own. Also the idea of Tubular Bells I found very exciting – the fact that there was just one person doing all these crazy things and that that was the way studio land was going. I dug that record for a long time. All that was going on, everything was possible, and that was how I operated. Now I’m in a place where, as long as you’re making music that you like when you listen back to it, I don’t really care how it’s done. Initially I was doing it all because I wasn’t very good at communicating what I wanted to other musicians. Manipulating the situation to get what you want was a lot harder than me just going into a room and playing everything. Then I got to a point where I could work with other people and tell them what to do, and then eventually I got to the point where I can work with people and not tell them what to do, and just play. That was great. I’ll do things in any way. I’m a completely eclectic omnivore when it comes to anything to do with sound and vision. I don’t have to be in a particular sound and space.

Why has it taken so long for you to play in the UK again?

I was just concentrating on one place. I started working with an American team when I was setting up the label. We’ve had some great times on the road, we’ve done all kinds of gigs in all kinds of permutations. Done more gigs in America before the aneurysm than I ever did before. Supported Steely Dan. That was really great. Played Australia for the first time. Playing to 30,000 at Bonnaroo with just three people – me on acoustic, a fiddle and an electric – I realised that, Wow, you can do this any way, really. They still cheered and roared even though there was no drums. That’s what it told me: it’s the words, music and melody. Coming here was something I wanted to do when I was back up to speed really, and it’s taken a while. Hopefully we’ll be coming back with a vengeance. I’d like the Albert Hall to be all singing and dancing World Party, and that’s what I’m working towards. About a nine-piece band and hopefully a small choir of some sort for “Thank You World”, “”All Come True” and “God on my Side”. Don’t want to give it all away!

And after that, a new World Party album?

We’ll do this for a while, and then think of a new album. I’m sure I’ll be in before the end of the year, getting back into the studio and clearing away the tumbleweed. I have a whole new bunch of stuff and I want to write some more. I’m not writing as prolifically at the moment, just making notes. I have this great multi-track thing on my phone, I can plug in my headphones and sing over the top of what I’ve played. That’s really good. [He demonstrates by whipping out his phone, putting his mouth over the speaker to create a pretty authentic wah-wah guitar sound over an existing tune]. I’d like to do an album on the iPhone. I think Damon Albarn did one. [He adopts seen-it-all comedy Northern voice] I’d like to do something good, though. Not like the kid... I’ve been lucky that I ended up here with the same things I had a long time ago and am able to still make music. And hopefully we can go on, make a lot of money and fuck everyone – get a cocaine habit and end up in a clinic. I think I’m old enough now for that.

- Arkeology is released on Monday. World Party play The Assembly, Leamington Spa, on October 28, O2 Academy, Oxford, on October 29, and the Royal Albert Hall on 1 November

Listen to new World Party song “Everybody’s Falling in Love”, recorded in 2011

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Pop Will Eat Itself, O2 Institute, Birmingham review - Poppies are back on patrol

PWEI hit home turf and blow the place up

Pop Will Eat Itself, O2 Institute, Birmingham review - Poppies are back on patrol

PWEI hit home turf and blow the place up

'Fevereaten' sees gothic punk-metallers Witch Fever revel in atmospheric paganist raging

Second album from heavy-riffing quartet expands sonically on their debut

'Fevereaten' sees gothic punk-metallers Witch Fever revel in atmospheric paganist raging

Second album from heavy-riffing quartet expands sonically on their debut

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Yazmin Lacey confirms her place in a vital soul movement with 'Teal Dreams'

Intimacy and rich poetry on UK soul star's second LP

Yazmin Lacey confirms her place in a vital soul movement with 'Teal Dreams'

Intimacy and rich poetry on UK soul star's second LP

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

Comments

Wow - thank you. A really

Love this interview &